过去几个世纪的气象观测

气象学一直是人类关注的主题。人类早期的著作中有大量关于气象的描述,例如洪水,这是所有文明中最常见的神话。在中世纪的欧洲,编年史学家直接记录天气事件(风暴,寒冷等),或通过葡萄收获日期间接记录。然而,直到16世纪末才出现了第一批对大气状况进行科学描述所必需的测量仪器。17世纪出现了观测网概念,目的是在量化的基础上描述地球气候的特征。早在1860年,电报以及更广泛的传输技术的发展使得通过气象观测预测天气成为可能。高空天气观测始于20世纪初。随着天气预报的发展,高空天气观测受到的关注与日俱增。自1960年以来,卫星被用于气象观测。今天,天气观测数据被存档和储存在数据库中,用于数值天气预报或气候变化模型。

1. 器测时期以前的观测

1.1. 最初的著作

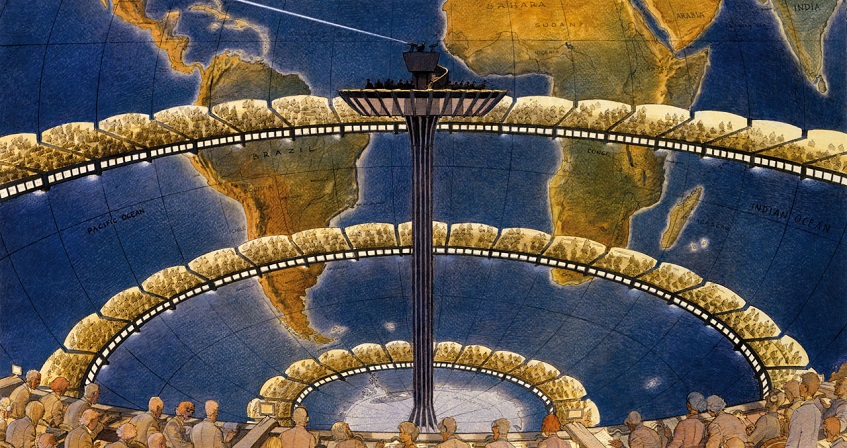

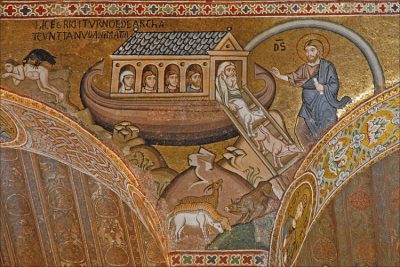

[图片来源:© 让·皮埃尔·达尔贝拉(Jean-Pierre Dalbéra),法国巴黎,CC By 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0),通过维基共享]

所有有关古代人类历史的文献都提到了天气事件,其中最著名的事件可能是洪水。摩诃婆罗多描述了一颗彗星划过地平线带来一场持续12年的暴雨。在《圣经》中,彩虹标志着洪水过后降雨结束,以及神与人之间的新约(见图1)。

中国的天气观测历史悠久。早在公元前1216年,就有文字记录了每十天一次的气象事件。文中甚至明确指出了风向。迦勒底或巴比伦的巫师也在泥板上留下了对天气现象的描述。希腊人认为气象学是一门科学。公元前334年左右,亚里士多德写了第一篇气象论文,将气象观测与物理现实而非神的行为联系起来[1]。

1.2. 中世纪到17世纪的欧洲

[图片来源:博恩市立图书馆]

历史学家埃马纽埃尔·勒·罗伊·拉迪里(Emmanuel Le Roy Ladurie)利用中世纪学者留下的编年史来了解人类历史及其遭受的气候灾害。他使用天气观测资料,如葡萄采摘日(图2)、收获日以及产量和质量,作为直接和辅助的资料来源。这些数据至少在这一时期对气象观测具有重要意义[2]。其他历史学家也使用了一些补充指标,例如,修改时间的实验报告[3]。有关预测天气的谚语(其中一些可以追溯到中世纪)也证实了人类观察天气并试图预测其变化。

2. 观测仪器

尽管有证据表明很早以前就有气象观测仪器,但大多数测量气象要素所需的仪器直到16世纪才被发明出来。

2.1. 气压计

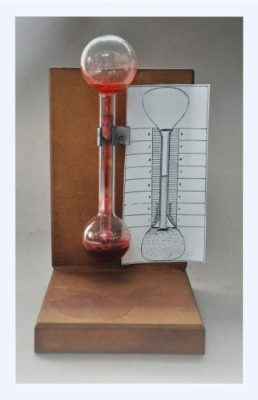

[图片来源:© D’ALENCE J.(1688) 关于气压计、温度计和气压计的论文,阿姆斯特丹]

托里拆利(Torricelli,1608-1647)第一个提出了气压计的原理,并在1644年通过一个充满水银的管子证明了大气压力的存在(图3)。帕斯卡(Pascal,1623-1662)在1648年指出,用托里拆利管测量的大气压力随着海拔的升高而降低。1663年,他发明了虹吸气压计[4]。1665年,英国科学家罗伯特·博伊尔(Robert Boyle,1627-1691)首次使用气压计这个名称[5]。从那时起,气压计经历了许多变化和发展,其中最重要的一个变化是卢西安·维迪(Lucien Vidie,1805-1866)对其进行的改进。卢西安·维迪为19世纪的科学考察提供了一种便携式、无汞仪器:无液气压计。无液气压计包括一个可变形的金属盒(称为维迪(Vidie)胶囊),盒内部分是真空。它的压缩受到弹簧的限制,弹簧的张力是压力的函数。维迪胶囊仍然是当今许多气压计的敏感元件。

2.2. 温度计

[图片来源:法国气象局]

即使我们知道古希腊的物理学家,如拜占庭的菲罗(Philo)或亚历山大的希罗(Hero)曾测量过气温的变化,但17世纪的几位科学家却声称应对气温变化负责。1611年,巴洛梅奥·泰利乌(Barlomeo Telioux)解释了温度计的原理,即可以通过测量水柱的高度来估计气压和温度的变化(图4)。

1612年,意大利医生桑托里奥·桑托里奥(Santorio Santorio,1561-1636)使用温度计来诊断病人的发烧情况[6]。1621年,荷兰人科内利斯·德雷贝尔(Cornelis Drebbel)发明了一种具有基本功能的温度计:把一个一端是玻璃气球的细长管插入装满水的容器中。水在管中升降。当病人把手放在球上时,释放的热量会使球体内的空气膨胀,并将水位降低到一定的高度。温度变化可通过定期重复实验并每次测量这一高度来监测[7]。

[图片来源:贾科莫·普契尼(Giacomo Puccini,公共领域),通过维基共享]

在1641年的佛罗伦萨,在托斯卡纳大公费迪南德二世的支持下,桑托里奥(Santorio)完善了温度计:将水置于一个密封管内以消除了大气压力的影响。德国的大卫·华氏(David Fahrenheit,1686-1736)通过将水银注入一个封闭的管中并通过标明刻度范围来提高其可靠性。瑞典人安德斯·摄尔修斯(Anders Celsius1701-1744)提出了一个标度,其中零相当于水的沸腾温度,100相当于冰的融化温度。将上述数值颠倒过来,这个标准就逐渐变成了现代水温变化的参考值。1954年,开尔文成为测量温度的国际单位,要从摄氏温度转换成开氏温度,需加上273.15。不过,世界气象组织(WMO)仍然使用摄氏温度。

2.3. 湿度计

列奥纳多·达·芬奇(Leonardo da Vinci)的《大西洋手稿》收集了许多从1478年至1518年间绘制的科学和技术图纸,其中一张图画有一个称重装置。一个托盘装有海绵,另一个托盘装有石头。这种称重装置可以测量空气湿度的变化,因为海绵的重量会随环境湿度的变化而变化,而石头的重量则保持稳定。这是气象学中使用的湿度计的雏形。

[图片来源:法国气象局]

前文温度计小节中提到的意大利人桑托里奥·桑托里奥(图5)也提出了几种可能测量湿度的方法。17和18世纪的几位科学家也发明了某些测量空气湿度的仪器。瑞士的霍勒斯·本尼迪克特·德·索绪尔(Horace Benedict de Saussure,1740-1799)发明了毛发湿度计(图6),这是一种简单、廉价、便携的仪器,长期以来一直用于气象观测[8]。

2.4. 风速计

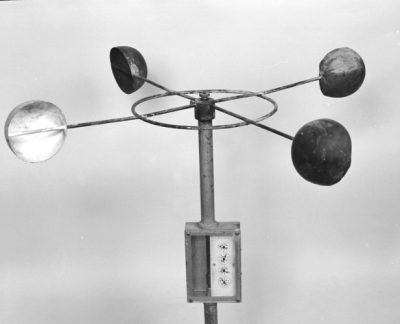

[法国气象局]

3. 观测网络

[图片来源:朱斯托·萨斯特曼斯(GiustoSustermans ,公共领域) ,通过维基共享]

测量仪器的发展使当时的科学家能够对测量结果进行比较,从而确定测量区域的气候特征。费迪南德二世(图8)托斯卡纳大公在西芒托学院的支持下为11个城市(佛罗伦萨,比萨,瓦隆布罗萨,库蒂利亚诺,博洛尼亚,米兰,帕尔马,奥瑞斯,奥斯纳布鲁克,因斯布鲁克,华沙)提供了气压计和温度计,并收集了10年的观测数据。1667年,天主教会的敌意终止了这一首个气象观测网络[10]。

1776年,法国皇家医学会创建了一个气象观测网络,以研究环境气候条件与疾病之间的联系。奥尔特里亚神父路易·科特(Louis Cotte,1740-1815年)组织该网络的运行:他列出了要使用的仪器,规定了仪器的安装和维护条件,提供了要填写的表格,并组织了仪器的收集和数据的归档。1784年,该网络包含了来自世界各地的76个观测站。位于曼海姆的普法尔茨气象学会选择了57家机构,从1780年起与其进行合作并交换气象观测数据。在1792年,法国大革命事件终止了这些观测网络的运作,幸运的是,由科特[11](图9)和普法尔茨学会收集的观测记录[12]被保留了下来。

[图片来源:法国气象局]

一些观测爱好者,尤其是农民和医生仍继续进行气象观测。在法国,直到1848年才出版了第一本《法国气象年鉴》,汇集了观测爱好者自发收集的气象观测数据。查尔斯·圣·克莱尔·德维尔(Charles Sainte-Claire Deville,1814-1876)和埃米利安·雷诺(Emilien Renou,1815-1902)于1852年提出并创立了法国气象学会(SMF),接管了该年鉴的出版工作。

专业气象服务机构的建立为不同的网络提供了必要的一致性,以便观测数据的实际应用。1864年奥本勒维耶(Urbain Le Verrier,1811-1877)在法国利用初级教师培训学院网络提供气象观测。1865年,部门气象委员会成立。1914年,这些委员会管理了一个由2000多名志愿观察员组成的网络(图10)。

[图片来源:法国气象局]

1847年,在德国成立了普鲁士气象研究所。气候学家威廉·马尔曼(Wilhem Mahlmann,1812-1848)定义了局地气候的概念,并组建了气象观测网络。在1833年创建的布鲁塞尔天文台,每天都有气象观测记录。阿道夫·凯特勒(Adolphe Quetelet,1796-1874)利用这些观测记录进行统计,并试图确定天气根据时间演变的物理规律。1850年成立了伦敦皇家气象学会,它将英国早在1848年出版的《每日新闻》中所有气象观测数据汇总在一起。早在1853年,海军上将罗伯特·菲茨罗伊(Admiral Robert Fitzroy)就提出了基于海上观测数据的预测规则,但美国人马修·方丹·毛利(Matthew Fontaine Maury)在同一年实现了海上观测数据的标准化,以便所有人都能使用。

詹姆斯·波拉德·埃斯佩(James Pollard Espy,1785-1860)向美国国会建议每个县都应配备气象站,包括气压计、温度计和雨量计。这些观测数据使他早在1841年就绘制出了天气图。然而,美国直到1870年2月9日才成立了气象局。

[图片来源:法国气象局]

1873年,世界气象组织在维也纳成立,第一任主席是英国人白贝罗(Charles-Henri Buys Ballot,1817-1890)(图11)。该组织的主要目的是交流气象观测数据,因此重点关注气象观测数据的标准化和定义其传输编码。

4. 观测数据的传输

1851年,在伦敦世界博览会上,电报公司展示了一张地图,上面显示了二十二个接受点的时间、风压和方向。通过电报或无线电快速交流气象观测结果使这些观测网络变得越来越重要。能够在收到观测数据几个小时内对其进行分析使得预测天气成为可能。观测数据不再仅仅只是用于研究气候。

[图片来源:彭·塔布雷特(P. Taburet),法国气象局]

1855年,奥本·勒维耶(U. Le Verrier)(图12)向拿破仑三世证明,电报气象观测网络的存在可以让他避免塞瓦斯托波尔灾难。

1854年11月14日一场风暴使得法国舰队损失惨重。如果有适当的观测网络,这场风暴本是可以预测到的。

1856年,法国决定建立一个国际气象服务机构,通过电报传送观测数据。

1857年11月2日,《巴黎天文台国际公报》发布了一份气象观测表。

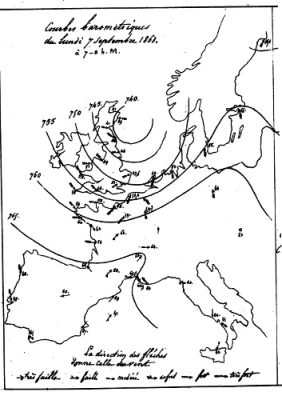

1863年9月7日,首张欧洲前一天的等压线地图问世(图13)。

[图片来源:法国气象局]

威尔海姆·布兰德斯(Wilhem Brandes,1777-1834)在其1826年的论文中率先绘制了四幅图,描述了1821年12月24日至26日从英国到挪威的强低气压路线[13]。

5. 高空观测

5.1. 探空气球

1898年,莱昂·泰瑟伦·德·博尔特(Léon Teisserenc De Bort ,1855-1913) 开始使用风筝和气球对大气进行垂直探测。 1899年,他论证了平流层的存在。 但直到第一次世界大战,人们才认识到这些观测的意义所在,并建立了一个探空站网络。

[图片来源:法国气象局,摘自ONM的报告和通信1925-1953/特拉普斯天文台]

1927年,罗伯特·伯克(Robert Bureau,1892-1965年)和皮埃尔·伊德拉克(Pierre Idrac,1885-1935年)发明了无线电探空仪,在地面上可以通过无线电接收气球携带仪器的测量数据(图14)。在卫星数据出现之前,这些观测数据是数值天气预报模式同化的主要观测数据。

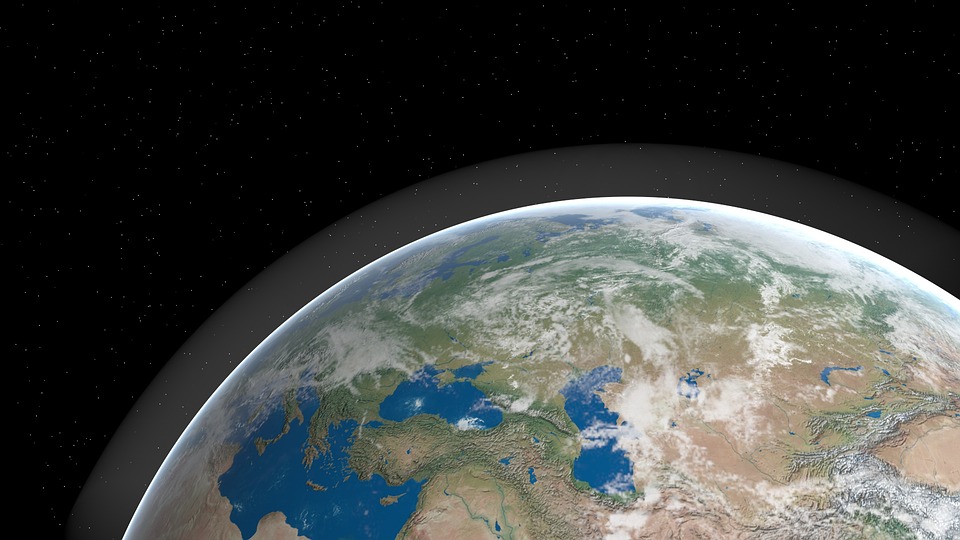

5.2. 卫星观测

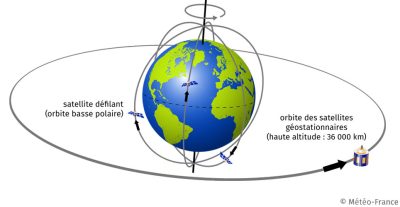

[图片来源:法国气象局]

satellite défilant (orbite basse polaire) :卫星(低极轨轨道)

orbite des satellites géostationnaires (haute altitude : 36 000 km):地球静止轨道 (高空:36 000公里)

1960年4月1日,第一颗气象卫星TIROS-1发射升空。1966年,地球同步卫星 ATS1提供了壮观的地球和大气云层图像。人们决定用气象卫星对地球进行全面观测。1974年,第一颗地球同步卫星American发射升空。1977年,欧洲卫星 Meteosat 发射升空(图15)。

5.3. 雷达观测

[图片来源:法国气象局]

1889年,海因里希·赫兹(Heinrich Hertz,1857-1894年)提出了通过电磁波检测金属表面的原理。第二次世界大战期间,当操作员例行使用雷达探测飞机时,发现了与降水有关的回波的存在。雷达测得的反射率与降水强度之间的联系(Z-R定律)得以确立。由此,美国气象局开发第一台降水探测雷达WSR-57。1980年代法国在安装了飞行雷达,如丹马丁的Melodi雷达(图16)之后,建立了为法国提供雷达气象覆盖的Aramis网络[14]。

6. 在数值天气预报和气候模式中的应用

6.1. 数值天气预报模式

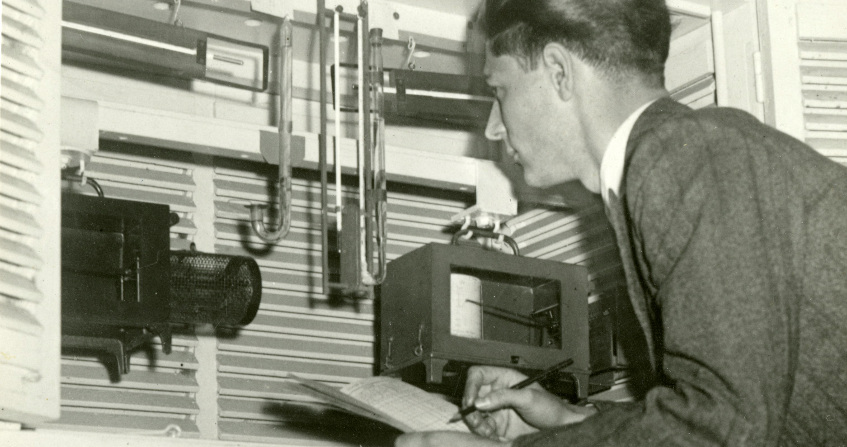

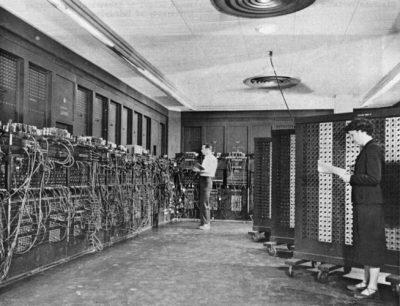

[图片来源:参见作者页面(公共领域) ,通过维基共享资源,美国陆军]

1922年,路易斯·弗莱·理查森(Lewis Fry Richardson,1881-1953年)提出了如何通过一组气象观测结果计算其演化的方法[15]。 1938年,卡尔·古斯塔夫·罗斯比(Carl-Gustav Rossby,1898-1957年)提出了更简单的方程来计算温带地区扰动的变化量。 1946年8月,约翰·冯·诺依曼(John von Neuman,1903-1957年)在普林斯顿组织了第一届“动态气象学和高速自动电子计算”会议。朱尔·查尼(Jule Charney,1917-1981年)设计了第一个模型,并于1950年3月在阿伯丁的ENIAC(图17,第一台数值天气预报计算机)上进行了测试。即使要花五周时间才能做出三次结论性预测,数值预报也算是成功进行了[16]。

1954年,通过人工分析气象观测数据,气象局发布了第一套24小时天气预报。在法国,直到1970年代随着Amethyst预报模型的发展,以无线电探空仪观测数据作为输入数据的数值预报才开始投入使用[17]。其预报范围仅限于法国市区,时间跨度为3小时[18]。

6.2. 气候模式

[图片来源:法国气象局]

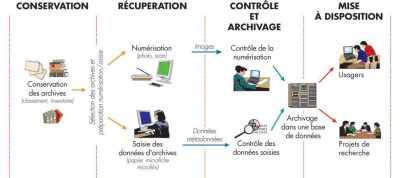

Conservation:保存

conservation des archives:档案保存

(Classement:分类; inventaire:清单)

Selection des archives et preparation numerisation/saisie: 档案选择及数字化准备/输入

Recuperation:恢复

Numerisation:数字化

Photo:拍照; scan:扫描

Saisie des donnees d’archieves 输入存档数据

(papier:文件; microfiche:缩微胶片; microfilm:缩微胶卷)

Images:图像

Donnees metadonnees:元数据

Controle et archivage:控制和存档

Controle de la numerisation:数字化控制

Controle des donnees saisies:检查输入的数据

Archivage dans une base de donnees:在数据库中存档

Mise a disposition:交付使用

Usagers:用户

Projets de recherche:研究项目

与数值天气预报模式不同,气候模式不需要一直输入气象观测数据,而是将观测数据用于定义大气的初始状态,然后模型根据已定义的规则和假设(例如,100年的温室气体含量[19])计算气候演变。此外,观测数据还被用于验证模型重建过去气候的能力,从而得出其与模拟的未来气候的相关性。气候模式使用的是均一化的气象观测数据,以消除它们在不同观测条件下的差异和变化。 世界气象组织(WMO)启动了一项庞大的气象观测记录恢复(数据救援)项目以便研究人员获得观测数据(图18),从而重建地球近期的气候[20]。

7. 需要记住的信息:

- 16世纪气象观测仪器的出现为气象观测提供了测量数据。

- 建立标准化的气象观测网络可以将测量数据转化为气候学观测数据,并对地球气候进行比较。

- 19世纪下半叶,电报的出现使得人们可以快速交换观测数据从而预测天气。

- 20世纪两次大战期间航空业的发展和气象资源的投入,使人们对大气有了更充分的认识。

- 20世纪70年代,计算机和卫星的发展标志着气象观测领域的一个转折点,气象观测被用于预测天气和研究气候变化。

参考资料及说明

封面图片:1950年代的气象观测。[图片来源:©法国气象局]

[1] FIERRO A. (1991). History of meteorology. Paris: Denoël

[2] THE ROY LADURIE E. (1967) History of climate since the year 1000. Paris: Flammarion

[3] LITZENBURGER L. (2015), A City Facing Climate: Metz at the End of the Middle Ages, Nancy: PUN

[4] PASCAL B. (1663) Treatises on the balance of liquors, and the gravity of air mass…Paris: Guillaume Desprez

[5] JAVELLE JP, ROCHAS M., PASTRE C., HONTARREDE M., BEAUREPAIRE M., JACOMY B. (2000), Du baromètre au satellite, Paris : Delachaux & Nestlé

[6] JAVELLE JP, ROCHAS M., PASTRE C., HONTARREDE M., BEAUREPAIRE M., JACOMY B. (2000), Du baromètre au satellite, Paris : Delachaux & Nestlé

[7] RENOW E. (1876), Histoire du thermomètre, Annuaire de la Société météorologique de France, n°24, http://bibliotheque.meteo.fr/exl-php/oaidoc/DOC00028778.html

[8] AVELLE JP, ROCHAS M., PASTRE C., HONTARREDE M., BEAUREPAIRE M., JACOMY B. (2000), Du baromètre au satellite, Paris : Delachaux & Nestlé

[9] JAVELLE JP, ROCHAS M., PASTRE C., HONTARREDE M., BEAUREPAIRE M., JACOMY B. (2000), Du baromètre au satellite, Paris : Delachaux & Nestlé

[10] FIERRO A. (1991). History of Meteorology, Paris: Denoël

[11] COTTE L (1774), Traité de météorologie, Paris: Imprimerie Royale http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k94863w

[12] SOCIETAS METEOROLOGICA PALATINA (1781-1786), Ephemerides Societatis meteorologicae palatinae, Manheim : Schwan, http://bibliotheque.meteo.fr/exl-php/vue-consult/mf_-_research_advance/ISO0000008104

[13] PARROCHIA D. (1998), Météores – Essay on the sky and the city, Paris:ChampVallon

[14] PARENT OF CHATELET J. (2003), Aramis, the French radar network for precipitation monitoring, La Météorologie, n°40, http://documents.irevues.inist.fr/handle/2042/36263(1922), Weather prediction by natural process, Cambridge University Press, https://archive.org/details/weatherpredictio00richrich

[15] RICHARDSON LF. (1922), Weather prediction by natural process, Cambridge University Press, https://archive.org/details/weatherpredictio00richrich

[16] ROCHAS M., JAVELLE .-P. (1993), La météorologie : la prévision numérique du temps et du climat, Aubenas : Syros

[17] PAILLEUX J., (2002), Les besoins en observations pour la prévision numérique du temps, La Météorologie, n°39, p29-35, http://documents.irevues.inist.fr/bitstream/handle/2042/36244/meteo_2002_39_29.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

[18] ROUSSEAU D., LE PHAM H, JUVANON DU VACHAT R. (1995), Vingt-cinq ans de prévision numérique du temps, La Météorologie, n°spécial, p129-134. http://documents.irevues.inist.fr/bitstream/handle/2042/52038/meteo_1995_SP_129.pdf

[19] PLANTON S., DUFRESNE J.-L. (2007), Description of a generic organizational chart, Le climat à découvert, p150-153, https:https://books.openedition.org/editionscnrs/11431?lang=en

[20] JOURDAIN S., ROUCAUTE E., DANDIN P., JAVELLE JP, DONET I., MENASSERE S., CENAC N., (2015), Le sauvetage de données climatologiques, La Météorologie, N°89, p47-55

环境百科全书由环境和能源百科全书协会出版 (www.a3e.fr),该协会与格勒诺布尔阿尔卑斯大学和格勒诺布尔INP有合同关系,并由法国科学院赞助。

引用这篇文章: PEPIN Marie-Hélène (2024年3月6日), 过去几个世纪的气象观测, 环境百科全书,咨询于 2025年4月5日 [在线ISSN 2555-0950]网址: https://www.encyclopedie-environnement.org/zh/air-zh/meteorological-observations-over-past-centuries/.

环境百科全书中的文章是根据知识共享BY-NC-SA许可条款提供的,该许可授权复制的条件是:引用来源,不作商业使用,共享相同的初始条件,并且在每次重复使用或分发时复制知识共享BY-NC-SA许可声明。