光的周期性与生物

PDF1.太阳周期和季节节律

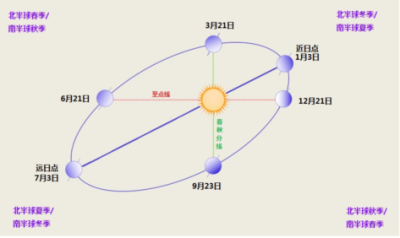

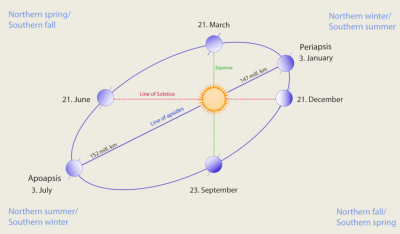

地球绕其自转轴以24小时一圈的旋转周期形成了昼夜交替。自从38亿年前地球上出现生命以来,已经发生了14 000亿个昼夜交替。地球绕太阳的公转周期,即地球年的时间是365.25天。地球赤道与公转平面(即黄道面)的倾角是23.5°。自转和公转共同影响了季节周期的形成。被太阳光直射的陆地面积是地球相对于太阳的位置的函数。由于太阳光的光子越接近垂直角度入射,其所传递给地表的能量也越大,产生的热也越多,这就是为什么我们能够区分夏天和冬天,以及中间的秋天和春天。在一年的不同季节,每天24小时中的白天长度也不相同,地轴相对于黄道面倾斜也是季节变化的缘由。因此,随着纬度的改变,白天的时长也随之变化。无论是南半球还是北半球,白昼最长的都是在夏至日,最短的一天在冬至日。因此,除赤道外,无论哪个地理区域,一年中每日白昼的长度变化与季节的年度变化紧密联系,而赤道处的每一天白昼长度都相同(图1)。

2.月相周期与生物

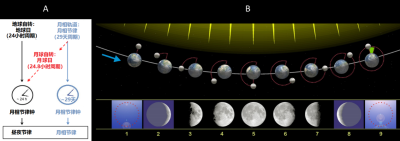

月亮受太阳照射,并反射太阳光。因此,在夜晚地球上可以看见月球,它的光照亮了大气层。月球绕地球旋转的一个完整周期为29天,月球绕其自转轴旋转的一个完整周期为24.8小时,太阳、地球和月亮的位置一直在不断变化,因而月球反光的部分和在地球上可以看到月球的部分也在持续的变化。大气层接收到的月光光照度变化很大:从新月的0.0001勒克斯到满月的1勒克斯。半月为 0.1 勒克斯,四分之一月为 0.01 勒克斯。

月球月是月球绕地球旋转一周的天数,在此期间地球还在绕太阳旋转(B):1&9. 新月(第0~29夜);2. 第一个新月(第4晚);3. 上弦月(第7夜);4. 渐盈凸月(第11晚);5. 满月(第15晚);6. 渐亏凸月(第18晚);7. 下弦月(第22晚);8. 最后一个新月(第26晚)。这种周期持续29天,生物内部主生物钟与之同步,并调节生物的行为和某些生理功能,包括生殖功能。月球日对应于月亮绕其自转轴旋转一周的时间,这一周期持续24.8小时,并与24小时的昼夜循环一起作用,使昼夜节律生物钟同步。A塔莱克根据克朗菲尔德-肖尔等人修改的图[1];B ©猎户座 8(CC By-sa 3.0)。来源:维基百科。

月相周期中光照强度的变化影响了生物体的行为和生物节律。尤其是月相周期通过改变环境的光照度,增加了对捕食风险的感知能力并且改变了生物的运动和饮食习惯。因此,大多数小型夜间哺乳动物会在满月之夜减少活动。相反,照度的增加往往有利于捕食者的觅食。生物节律也随月相周期而变化。在某些物种中,月相周期使个体之间的繁殖周期同步,如两栖动物和珊瑚。这些行为和节律将受29天的月相节律诱导和同步化。但是迄今还缺乏深入研究,其相关机制和光受体都还没有确定(图2)。

参考和引用

[1] 克隆费尔德-肖尔 ·N, 多米诺尼·D, 伊格莱西亚·De H, 李维·O, 赫尔佐格·ED, 达扬·T & 赫尔弗里希-福斯特·C (2013) 月光下的时间生物学,皇家学会论文集,生物科学280, 1-11.

延申阅读

勃莱德肖·WE & 浩尔萨普费尔·CM (2007) 动物的光周期进化。生态学、进化学和系统学年度评论 38, 1-25

CEA,法国原子能委员会(2009)。太阳,CEA版本

寇卡利·WL & 索特恩·RB (2006) 生物节律概况. 纽约, 斯普林格出版社

Light cycles and living organisms

PDF1. The solar cycle and seasonal rhythms

2. The lunar cycle and living organisms

Illuminated by the sun, the Moon reflects its light. At night, the Moon is therefore visible from the Earth and its light illuminates the atmosphere. The lunar cycle lasts 29 days for a complete rotation of the Moon around the Earth and 24.8 hours for a complete rotation of the Moon on its own axis. Sun, Earth and Moon are constantly changing positions. As a result, the portion of the Moon illuminated and visible from the Earth also changes. The illumination of our atmosphere varies greatly: from 0.0001 lux at the new moon to 1 lux at the full moon. It is 0.1 lux for a half moon and 0.01 lux for a quarter moon.

References and notes

[1] Kronfeld-Schor N, Dominoni D, De Iglesia H, Levy O, Herzog ED, Dayan T & Helfrich-Forster C (2013) Chronobiology by moonlight. Proceedings of the Royal Society: Biological Sciences 280, 1-11.

Further reading

Bradshaw WE & Holzapfel CM (2007) Evolution of animal photoperiodism. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, & Systematics 38, 1-25.

CEA, French Atomic Energy Commission (2009). The Sun. CEA editions.

Koukkari WL & Sothern RB (2006) Introducing biological rhythms. New York, Springer Verlag.