哺乳动物和灵长类动物色觉的进化

PDF在非哺乳类脊椎动物中,参与视觉和非视觉光感受的器官包括侧眼及眼外光受体:松果体、松果旁体、额叶、顶眼和深脑光受体。众多的器官参与可以使生物体能同时收集到一个光源的多方面信息,如光的周期性、光强和光谱等,因而能够减少对光信息的误判、对光和时间的测量更为精细。然而,在哺乳动物中,视觉和非视觉光感受仅由眼睛来完成。这种特异性可能与它们的进化有关,因为它们的共同祖先是2.25亿年前出现的夜行性动物,直到今天,还有63.8%的哺乳动物只在夜间活动。在黑暗中导航需要灵敏地区分光照强度或光谱的微小变化,由于只有眼的结构足够敏感,可以区分这些细微的变化,因此哺乳动物逐渐丢弃了眼外光受体。在夜间活动的非哺乳动物中也可以观察到类似的现象,如壁虎就没有顶眼。

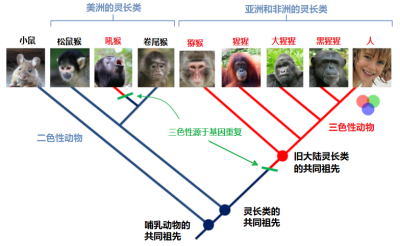

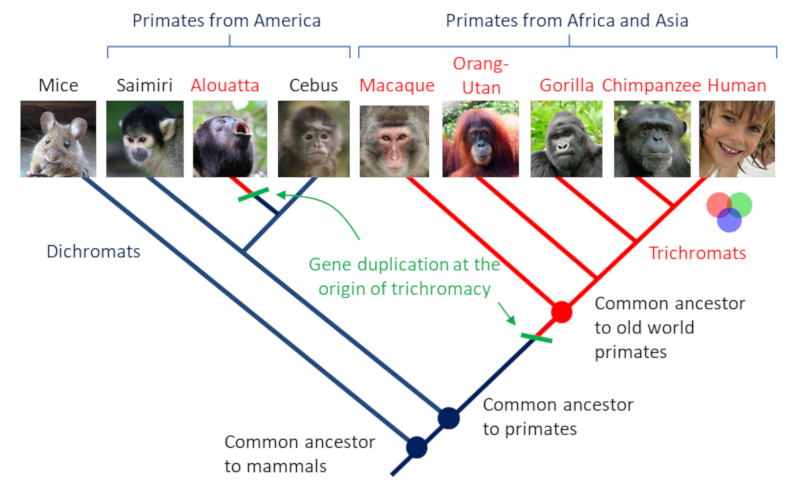

虽然灵长类跟其它哺乳动物的共同祖先是二色生物,但是一些灵长类动物与它们不同,它们(包括人类)再次获得了三色视觉。狭鼻猴(旧大陆猴)和吼猴(南美吼猴)中有SWS1、MWS和LWS三个基因,分别编码三种类型的视锥体。阔鼻猴(新大陆猴)中存在两个基因,其中一个是复等位基因(有几种形式的相同的SWS1基因和三种LWS等位基因),并与X染色体相连。换句话说,物种中只有杂合子的雌性,即有两个不同的LWS等位基因,才有三色视觉;有两个相同LWS等位基因的纯合子的雌性和只有一条X染色体和只有一个LWS等位基因的雄性是二色性的。物种重新拾起三色性的原因是什么?一种可能性是,具有三色性视觉的灵长类动物能够更好地从植被的绿色背景中辨别出成熟的红色果实,因而具有选择优势。事实上,MWS基因和其中一个LWS等位基因编码对绿色敏感的视锥蛋白。

人类所属的猫鼻猴(”古老世界”的猴子:非洲和亚洲)具有三色视觉,而扁鼻猴(”新世界”的猴子:南美洲)除Aluaites外,具有二色视觉。 后者只有SWS1基因(编码蓝色视蛋白)和祖先LWS基因编码红色视蛋白。这些人看到的是红色和蓝色。该基因的复制是三色视觉(蓝色,绿色和红色)的起源。老鼠(不是灵长类动物)在这里被指示以显示灵长类动物和其他哺乳动物的分离。图中所有其他物种都是灵长类动物。

照片来源(维基百科):亚马孙松鼠猴(Saimiri boliviensis) © Julie Langford (CC BY 3.0); 吼猴 © Cephas, Simon Pierre Barette (CC BY-SA 4.0);白额卷尾猴(Cebus albifrons) © Rama (CC BY-SA 2.0-en); 日本猕猴(Macaca fuscata) © Alfonso Paz Photo (CC BY-SA 3.0);猩猩 (c) Lionel Leo (CC BY-SA 3.0);大猩猩 (c) 英国的Carine06 (CC BY-SA 2.0);黑猩猩 © Clément Bardot (CC BY-SA 4.0); 人 © A. Durand (CC BY-SA 3.0)。

参考和引用

[1] 修改自

译者:文静 审校: 崔骁勇 责任编辑:胡玉娇

Evolution of colour vision in mammals and primates

PDFIn non-mammalian vertebrates, visual and non-visual light reception involves ocular, lateral and extraocular photoreceptor structures respectively: pineal organ, parapineal organ, frontal organ, parietal eye and deep brain photoreceptors. These different organs allow individuals to collect, from a single light source, various information such as photoperiod, light intensity and electromagnetic spectrum. This makes it possible to reduce misinterpretation and refine the measurement of light and therefore the measurement of time. However, in mammalian species, visual and non-visual photoreceptions involve only ocular structures. This particularity could be linked to their evolution since a common nocturnal ancestor appeared 225 million years ago. Nowadays, 63.8% of mammals are nocturnal. However, navigating in darkness requires very sensitive structures that can distinguish minute variations in light intensity or the electromagnetic spectrum. Only the ocular photoreceptor structures are sensitive enough to distinguish these variations. This constraint would have led mammals to lose their extraocular photoreceptor structures. This is also observed in nocturnal non-mammalian species such as geckos that have lost their parietal eyes.

However, some primates are the exception. Indeed, while their common ancestor was dichromate, several species (including humans) have once again acquired the trichromatic vision. Thus, among catarhins (monkeys of the “Old World”) and alouates (South American howler monkeys), there are three genes, called SWS1, MWS and LWS, that code for three types of cones. In platyrhinians (monkeys of the “New World”) there are two genes, one of which is poly-allelic (there are several forms of the same SWS1 gene and three LWS allelic forms) and linked to the X chromosome. In other words, for these species, only heterozygous females, which have two different LWS alleles, have trichromatic vision; homozygous females, which have two identical LWS alleles and males, which have only one X chromosome and only one LWS allele, are dichromatic. The reason for a return to trichromatics? It seems that the trichromatic vision has given these primates a selective advantage in distinguishing ripe red fruits on the green background from vegetation. Indeed, the MWS gene and one of the LWS alleles encode cones that are sensitive to the green color.

References and notes

[1] Adapted from http://acces.ens-lyon.fr/acces/ressources/neurosciences/vision/enseigner/pigments-retiniens-et-evolution/les-pigments-retiniens-des-outils-pour-retracer-l2019evolution