法国水法

水这一自然资源在水循环中永久流动,因而难以通过法律进行把控。水的流动是显而易见的,然而将其纳入法律却需要时间。直到近些年人们才开始关注水资源的一体性和全球性属性: 1960年代初,法国把流域概念纳入了法律中。水法的表述并非确定无疑。本文主要探讨两个问题:法国是如何制定水法的?构成水法的主要要素是什么?

1. 水——流动不止的资源

水是不断流动的自然资源,很难通过法律加以把控。正所谓“世界上最好的法律也无法让一滴雨落下。”[1]

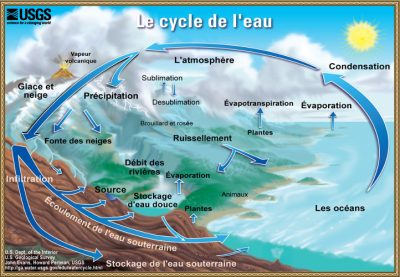

(图片来源:维基百科 By USGS Georgia Water Science Center Illustration by John M. Evans, Howard Perlman, USGS French translation by Monika Michel, Agence de l’Eau Artois-Picardie, Grance [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons)

Le cycle de l’eau 水循环 Condensation 冷凝Evapotranspiration 蒸腾Vapeur volcanique 火山蒸汽 Glace et neige 冰雪 Evaporation蒸发L’atmosphère 大气层 Précipitation 沉淀 Brouillard et rosée 雾与露水Sublimation 升华 Desublimation 去升华 Fonte des neiges 雪融化Ruissellement 径流 Plantes 植物 Débit des rivières 河流流量 Intiltration 渗透 Évaporation蒸发Source 来源 stockage d’eau douce 淡水贮存 Animaux 动物Les océans. 大洋 Ecoulemnent de l’eau souterraine地下水流动Stockage de l’eau souterraine 地下水贮存)

在成为可利用的自然资源之前,水是一个自然系统(图1)。虽然水循环是一个显而易见的事实,但是将其纳入法律却需要时间。法律考虑到水的一体性和全球性是最近才出现的现象。事实上,法律长期以来忽视了地表水和地下水之间的相互依赖关系。直到20世纪初,“流域”这个法律概念的出现[2],才为水资源受法律保护奠定了基础。地表水和地下水具有一定的不可分割性,不应该被分开来看待。

水资源与法的关系源远流长,在水管理方面,罗马法给后世很大启发。正如著名地理学家皮埃尔·乔治所说[3],罗马文明是最伟大的水文明之一。罗马人留下的最伟大的遗迹便是渡槽,如法国的加尔桥(图2)。经久不衰的古代渡槽突显了罗马人的建筑天赋及卓越的组织能力。为了建设、维护和管理水利,罗马在建造运河和浴场的同时,建立了一整套行政和立法体系[4]。图拉真大帝时期,负责管理水域的大臣弗朗廷(Frontin)在他关于罗马渡槽的论著中,对这种水资源管理进行了非常详尽的描述[5]。罗马法律规定可以自由使用公共用水。公共用水指常年流淌的水,如河流中的水。此外,公民如果获得特殊授权,也可将公共用水私有化。

(图片来源:维基百科,摄于Wolfgang Staudt)

自1960年代起,水法适时对水质提供了法律保障[6],主要关注点是控制地表水的化学污染。 水资源保卫战是通过减少或消除水资源污染以保护公共健康或保障水道通航。水资源保护的本质完全是人类中心主义的,即为了人类的利益,而非为了环境。

如今,对于水环境的保护不能仅从服务人类的角度来考虑,这会导致忽视水资源在维持生态系统平衡方面的重要作用。然而,如果仅从“生态中心”角度出发来保护水资源,也同样会忽视水与人类之间的紧密联系。对水资源的任何破坏总是必然导致对人类的损害,因为人类的环境受到了破坏[7]。反之,“为自然服务也就是为人类服务”[8]。

在法国法律中,水法具有长期复杂性的特点。水资源的法律地位和制度缺乏统一性,且与水的所有权密切相关。民法典[9]规定,水是公有财产,不属于任何人。其使用权归所有人共有。此外,1992年1月3日的《水法》规定水资源是国家的公共遗产[10]。然而,《国有财产法典》第L. 2111-7条及以下条款对受公法管辖的国有水道和受私法管辖的非国有水道进行了区分。最终,这种复杂性和混淆性损害了整体水资源保护的有效性。

2. 水权的定义

水权一词没有法律定义。与环境法不同,法国立法者还没有起草专门的水法典[11]。目前,适用于水资源的法律法规分散在多部法典中。例如,水资源管理规划受《环境法》管理,公共饮用水服务受《地方法》管理,河流公共领域受《国有财产法典》管理,水污染犯罪受《刑法》管理等。

由于长期以来水资源政策显示出零散化特征[13],法国的一些学者仍在质疑水权的相关性[12],但也有人试图界定水权的内容。一些人认为,水法是指“确定水的法律制度,个人可以行使的权力以及保护水资源必须采取的措施的一些列规则”[14]。另一些人认为,水法是“一套管理全球大陆水域的规则……是与水资源各方面相关的法律体系,涵盖了自然环境和人文环境之间的相互关系[15]。水法对水资源和水生环境的保护涉及保护水质和水量两个方面。

3. 水权的历史沿革

在法国,水权是在“三大水法“的影响下逐步确立的,为后来建立真正的水资源管理机构打下了基础。即使水法尚未成熟,但在欧盟法律的影响下,水法仍在不断完善,以更好地保护水资源。因此,欧洲标准有助于“全球化统一水法”的构建[16]。

3.1 实施“三大水法”

在法国实施的“三大水法”奠定了现代水法的基础,分别是:

- 1964年12月16日颁布的关于水资源管理和分配以及防治污染的法律。

- 1992年1月3日颁布的第二部水法。

- 2006年12月30日颁布的水与水生环境法。

1964年12月16日颁布的第一部水法是为治理水污染而建立的[17]。该法的通过是防止污染的重要一步,也是保护作为共同遗产的水资源的重要一步。立法机关以流域为单元设立行政区,明确指出造成水污染的犯罪者需承担法律责任。

随后,1992年1月3日的法律首次对水的法律制度进行了统一[18]。因此,水权围绕四项主要原则进行了整合:水资源统一原则[19]、水遗产原则、确认水资源保护的普遍利益以及水资源的均衡和可持续管理原则[20]。该法规定,根据工程的重要性,以及所涉及的妨碍公共健康和水体自由流动的风险因素,对所有非家用目的而进行的工程、安装、活动统一实行单一的授权和申报制度。

此外,立法机关围绕两个规划文件组织水资源管理,即《水资源开发与管理总体规划(SDAGE)》[21]《水资源开发与管理规划》(SAGE) [22]。《水资源开发与管理总体规划》是针对水文流域尺度制定的为期六年的规划文件,而《水资源开发与管理规划》是针对于更小的尺度,即子流域尺度制定的,能将某一地区的具体情况考虑在内。为实现《水框架指令》设定的目标,即所有水体达到良好的生态状况,《水资源开发与管理总体规划》界定哪些区域实施《水资源开发与管理规划》。根据该法,城市规划文件(区域协调计划、地方城市规划和市政地图)必须与《水资源开发与管理总体规划》相一致。2016-2021年,法国对《水资源开发与管理总体规划》进行了修订和更新。例如,针对罗纳-地中海盆地的最新版水资源开发与管理总体规划》于2015年12月21日生效,有效期为6年[23]。

2006年12月30日[24]的水法保留了1992年第二部水法的原则。该法的新增内容包括承认人类用水的优先权,以及为各个收入水平的公民提供饮用水保障[25]。

此外,本法加强了《水资源开发与管理规划》的法律范围,因其与《水资源开发与管理总体规划》一样具有完全监管价值。法律规定,规划中所包含的法规和制图文件可以强制要求第三方在水警部门的管辖下进行工程施工、安装或活动[26]。不过根据政策要求,《水资源开发与管理规划》项目需事先接受公众调查。

3.2 在水利部门设立专门机构

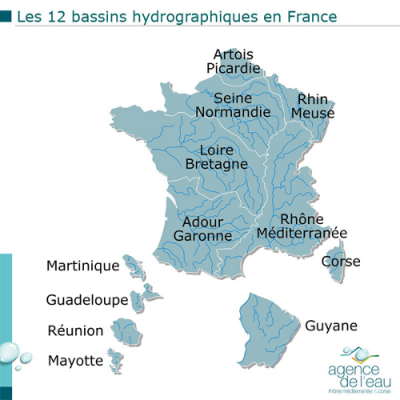

(图片来源:罗纳-地中海-科西嘉水务局)Les 12 bassins hydrographiques en France法国的12个河流流域,Artois Picardie阿图瓦尔—皮卡底流域,SeineNormandie诺曼底塞纳河,Rhin Meuse莱茵河-默兹河,LoireBretagne瓦尔塔卢瓦尔河-布列塔尼,Adour Garonne阿杜尔河-加隆河,RhoneMéditerranée罗纳河-地中海,Martinique马提尼克,Corse科西嘉,Guadeloupe瓜德罗普, Réunion留尼汪,Mayotte马约特,Guyane圭亚那,agence de leau 水务署)

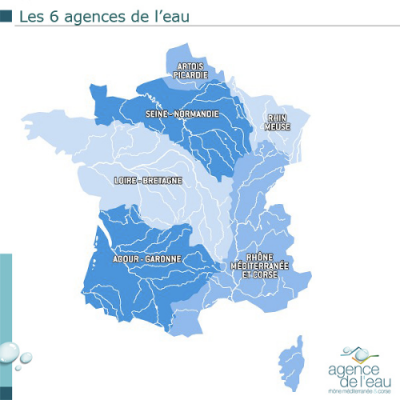

法国境内划分为12个主要流域(图3),其中7个位于本土[27]。国家一级的水资源管理机构主要发挥咨询作用,而流域内的水务局才是真正的决策机构[28]。首先,流域区的流域总协调员[29]需要具备一定专业知识以确保地方水资源管理的一致性和合理化。例如,负责批准流域《水资源开发与管理总体规划》。此外,协调员还担任在每个流域或流域组设立的流域管理委员会主席一职。该委员会的作用主要是提供咨询,协助流域协调员行使权力,并就《水资源开发与管理总体规划》、措施方案和洪水预报总体方案征求其意见。

(图片来源:罗纳-地中海-科西嘉水务局)

根据2005年5月16日[30]的法令,每个流域都设立了一个流域委员会,也称为“水议会”,在流域内发挥咨询和领导作用。委员会的成员由3部分组成,其中40%是地方政府[31]的代表,40%是用水户代表,20%是政府代表。

流域委员会负责制定和修订《水资源开发与管理总体规划》,并对制定子流域的《水资源开发与管理规划》[32]提供指导性建议。在法国,流域委员会在落实水利部门参与原则方面的作用体现在流域水生自然环境委员会中。流域委员会主席可向该委员会咨询有关水生自然环境保护的《水资源开发与管理总体规划》方针,或有关流域水生环境的任何问题。

此外,各个流域成立的水务局[33]在贯彻落实水资源的均衡和可持续管理方面发挥着重要作用。水务局是根据1964年的法律设立的。1991年以前,其前身为流域财政机构,原则上与流域委员会并行运作。如今的水务局为国家公共管理机构[34],设立在各个流域或流域组,并受环境部的监督。

水务局的职责是落实《水资源开发与管理总体规划》和《水资源开发与管理规划》,促进水资源和水环境的均衡经济管理,保障饮用水供应,防洪,促进经济活动的可持续发展。此外,水务局还执行经流域委员会批准的保护湿地[35]的土地政策:水务局可以收回这些地区的土地,以解决土壤人为退化等问题。这项湿地保护政策已经过时。自1971年签署了《关于特别是作为水禽栖息地的国际重要湿地公约》(简称《湿地公约》》,又称《拉姆萨尔公约》)以来,法国一直致力于湿地保护。 2016年8月8日,法国颁布了《生物多样性恢复、自然与人文景观法令》,将水务局的职责扩大到保护海洋环境,以及陆地和海洋生物多样性。

水务局的财政来源主要包括向公共和私营实体收取的费用、偿还的预付款以及公共实体支付的补助等七类。

按照预防原则和环境破坏修复原则,水务局向机构和个人征收水污染处理费、水资源集约化网络建设费、面源污染处理费、水资源取水费、枯水期蓄水费、河道清障费以及水生环境保护费[36]。水务局的财政预算来自这些税收,并以补助金的形式发放给地方政府或缔约机构(市政局、市政组织、农民、企业家),主要用于资助水污染防治行动。其中,水务局约73%的预算来自生活污水收费[37]。因此,为水务局提供的财政预算资金的的大多是家庭用水消费者,而非大多数人认为的农民或企业家。

法国本土设有6家水务局管辖7个本土流域:阿图瓦—皮卡底,莱茵河-马斯河,塞纳河-诺曼底流域,卢瓦尔-布列塔尼流域,阿杜尔-加龙河流域,罗纳河-地中海-科西嘉流域,海外省设有4家水务局,分别管辖4个流域(瓜德罗普岛,法属圭亚那,马提尼克岛,留尼汪岛)。马约特岛是唯一一个设立水务局的省份,但它设有一个流域委员会。

在子流域一级,设立了地方水利委员会,负责跟踪、审查和监督《水资源开发与管理规划》[38]的实施情况。该委员会由三个不同的组成部分: 地方政府及地方公共机构、水用户协会和国家及相关公共机构代表。

最后,法国还有其他机构也会参与水资源管理和保护,例如地方性的公共流域机构[39]、环境领域的公共利益团体(业主工会协会,以及更普遍的环境保护协会)。

3.3 国际法原则

一直以来,国际法都是根据领土主权原则来处理水资源问题。该原则承认,各国有专属的权利,可根据其国内法对其领土管辖范围内的水资源进行管理[40]。自然资源的永久主权原则在1960年代被认为是各国民主主权的一部分[41]。对自然资源领土主权原则的明确表述是“每个国家对其所有财富、自然资源和经济活动拥有充分和永久主权,包括拥有、使用和处置它们的权利”[42]。然而,各国人民在处置作为原材料的资源和处置重要资源之间并无区别[43]。此外,这一权利没有考虑到自然水循环的全球性属性,存在不平等分配。因此,各国人民处置其资源的权利并不能保障他们的水资源得以供应和受到保护,并且有可能将水资源交易置于市场经济规律的波动中。

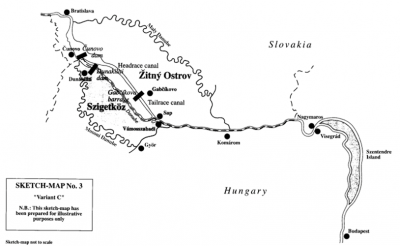

(图片来源:联合国国际法院,Bratislava 布拉迪斯拉发,Slovakia斯洛伐克,Hungary匈牙利,Komárom科马罗姆,Visegrid维斯格里德,Budapes 布达佩斯,Gabikoro加比科罗,Gyór乔尔,Srentendre Island斯伦特雷岛,N.B.: This sketch-map has been prepared for illustrative purposes onlyble a eds注:此示意图仅作说明之用)

然而,水资源的领土主权是通过尊重不造成损害原则和尊重水资源的公平使用原则发展起来的。这些限制主权原则是由国际法院在1997年9月25日判决的匈牙利和斯洛伐克之间关于盖巴斯科夫–拉基玛洛大坝案中确立的(图7)[44]。

不造成损害和公平使用原则与合作原则密切相关。换句话说,如果没有跨界河流沿岸国的相互合作,这些原则就无法得以执行。事实上,国际法院认为“合理、优化使用河流水资源是该合作体系的基石[45]”。根据公平和合理使用水资源的原则,沿岸国必须定期交换关于跨界流域的开发利用规划和水情变化信息。国际法院认为,必须在“一方面将河流用于经济和商业目的开发,另一方面保护河流免受此类活动可能对环境造成的任何损害”[46]之间取得平衡。

不造成损害的原则有一定局限性,因为在实际适用时受到公平合理用水原则的制约。公平原则旨在充分考虑河流自然和地理条件,同时协调各国在水资源方面的利益。

归根结底,由于涉及国家领土主权的权利,国际法并没有为保护整个水资源提供有效的解决方案。

3.4 欧盟法的影响

欧盟法与国际法的不同之处在于,它具有更大的约束力,且适用于所有成员国。此外,欧盟法特别考虑到地表水和地下水之间的相互依存关系。

法国水法是在欧盟法的影响下发展起来的。从2000年起,欧盟立法者开始认识到资源的有限性和保护水质的必要性,同时关注到水的自然循环、流动性质、河流中生命体、河流生态系统和水体环境等问题。

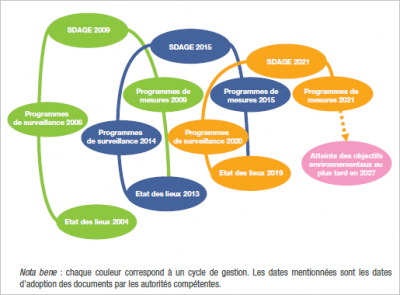

(SDAGE 2000 水资源整治与管理总体规划纲要2000,SDAGE 2015水资源整治与管理总体规划纲要2015,SDAGE 2021水资源整治与管理总体规划纲要2021,Prograrnmes de mesures 2000 实施方案2000,Programmes de mesures 2015 实施方案2015,Programmes de mesures 2021 实施方案2021,Programmes de surveillance 2008 监管计划2008,Programmes de surveillance 2014监管计划2014,Programmesde surveillance 2000监管计划2000,Etat des lieux 2019 2019现状,Etat des lieux 2013 2013现状,Etat des lieux 2004 2004现状, Atteinte des objectifis environnementaux au plus tard en 2027 到2027年实现环境目标,Nota bene: chaque couleur correspond à un cycle de gestion. Les dates mentionnées sont les dates d’adoption des documents par les autorités compétentes注意:每种颜色对应一个管理周期。所述日期为主管当局通过文件的日期)

2000年12月22日颁布了《水框架指令》[47],此后,通过了一系列有关自然水循环水质和水量保护原则的全球标准[48],要求各成员国将其纳入本国法律 (图8)。法国在2004年4月21日将该指令纳入本国法律[49],由此确立了法国水资源管理目标,包括到2015年前实现水体的良好生态状况。

根据该指令,水资源从自然界的源头到消费者的水龙头的整个循环中都受到了保护。此外,欧盟立法者还规定了各成员国达到《水框架指令》中规定的水质和水量目标的最终期限。因此所有欧盟成员国,尤其是法国,都必须遵守欧盟法律设定的目标,否则就有可能被欧盟法院定罪。该指令的目标是在2015年12月之前实现欧盟领土上所有水体的良好生态状态。如有正当的减损理由,也可推迟到2021年或2027年。目前,法国远未实现这一目标,法国政府甚至多次要求欧盟委员会延长该指令设定的最后期限。

该指令还反映了各成员国协调其水资源法律制度的意愿。指令指出“水与其他商品不同,它是一种遗产,必须作为遗产加以保护、捍卫和对待。”[50]。然而,欧盟法律并没有因此承认饮用水的权利。欧盟成员国可以自由选择直接管理公共饮用水服务或委托该领域的大公司进行间接管理。

最后,正如最高行政法院所指出的,该指令“通过改变其方法,重新实现了水法的一致性,虽然这样做对部分成员国带来了阵痛。该指令从长期应实现的结果出发,定期就其实现情况提交报告。[51]《水框架指令》生效后,接着颁布了其他指令[52]作为补充条例,不断加强和巩固了对水资源的保护和水法的建设。

4. 文章提要

- 在法国,由于与水资源保护和治理的法规分散在若干法典、法律、法令等中,水法仍是十分复杂且难以获取的权力。

- 而在欧盟法律的影响下,水资源的法律框架将更多地考虑到其自然循环、生态现实、自然环境和水生环境。

参考资料及说明

封面图片:大坝(38). 维基百科. By Parisdreux (Own work)[CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons]

[1] GAZZANIGA J.-L., LARROUY-CASTERA X., Le droit de l’eau et les droits d’eau dans une perspective historique, in AUBRIOT O., JOLLY G. (coord.), (2002), Histoire d’une eau partagée (Provence, Alpes, Pyrénées), Publications de l’Université de Provence, Aix-en-Provence, p.18.

[2] 所谓水文流域,是指由同一水文网络,即由主干水道的一组支流灌溉的一组土地, RAMADE F., (2002) Dictionnaire encyclopédique de l’écologie et des sciences de l’environnement, Dunod, Paris, 2nd edition, p. 734.

[3] GEORGE P., (1984-1985), Water in Mediterranean Civilizations and Economies, Paralelo, No. 37, Revista de estudios geograficos, Volumen Homenaje a Manuel de Teran, No. 5-9, p. 299.

[4] MALISSARD A. (2002), The Romans and Water. Fountains, bathrooms, thermal baths, sewers, aqueducts… Les Belles Lettres, Paris, p. 309.

[5] FRONTIN, Les aqueducts de la ville de Rome, text prepared, translated and commented by P. Grimal, 3rd ed., Paris, Les Belles Lettres, 2003, p. 113. It is a treaty on the water system in Rome at the height of the Empire written between 97 and 103 AD.

[6] 此外,值得注意的是,法国早在 1669 年就颁布了保护水和森林资源的皇家法令,禁止在河流中倾倒垃圾和废物。

[7] FABRE-MAGNAN M., Postface. Pour une responsabilité écologique, in NEYRET L., MARTIN G. J. (dir.), (2012), Nomenclature des préjudices environnementaux, L.G.D.J., Paris, p. 393.

[8] MORAND-DEVILLER J., (2010), Le droit de l’environnement, 10th ed., PUF, Paris, coll. Que sais-je?, p. 5.

[9] Art. 714 of the Civil Code.

[10] 该法条款1规定: “水是国家共同遗产的一部分。在尊重自然平衡的前提下,对水及可利用资源的保护开发是普遍关心的问题。在法律法规和先前确立的权利框架内,水的使用属于所有人。”

[11] 不过,应该指出的是,《水法》是现行法律规则的汇编。 参见 DROBENKO B. and SIRONNEAU J., (2013), Le Code de l’eau, 3rd ed., Johanet, Paris, XII-105 p.

[12] 值得注意的是,在一些国家如西班牙或意大利,使用的术语是 “水法 “或 “水资源法”。

[13] SAOUT A., (2011), Théorie et pratique du droit de l’eau, Johanet, Paris, 472 p.

[14] GAZZANIGA J.-L., OURLIAC J.-P., LARROUY-CASTÉRA X., (2017), “Eaux”, JurisClasseur Rural, fasc. 10, § 10.

[15] JÉGOUZO Y., (2010), “Is there a right to water? “, in Report of the State Council, Water and its Law, vol. II, La documentation française, Paris, p. 567.

[16] Ibid. at 570.

[17] Law No. 64-1245 of 16 December 1964 on the regime and distribution of water and the fight against pollution, JORF, 18 December 1964, p. 11258.

[18] Water Act No. 92-3 of 3 January 1992, JORF, No. 3, 4 January 1992, p. 187.

[19] 这是一个考虑到水资源及其自然循环的物理现实的问题。

[20] JÉGOUZO Y., (2010), “Is there a right to water? “, op. cit. , p. 570.

[21] SDAGE 由流域一级的流域委员会制定。

[22] SAGE 由分流域一级的当地水务委员会制定。

[23] 该文件可在罗纳-地中海盆地官方网站上查阅: www.rhone-mediterranee.eaufrance.fr.

[24] 2006 年 12 月 30 日第 2006-1772 号关于水和水生环境的法律, JORF No. 303 of 31 December 2006, p. 20285.

[25] 第一条,编入《环境法》第 L. 210-1 条。

[26] 《环境法》第 L. 212-5-2 条。

[27] 依据《环境法》第 L.213-13 条及其后条款,这六个流域是 卢瓦尔-布列塔尼流域、罗纳河-地中海-科西嘉流域、阿杜-加龙河流域省、塞纳河-诺曼底流域、阿图瓦-皮卡第、莱茵-马斯河流域。自 2002 年起,科西嘉岛拥有一个水文流域。自 2003 年起,海外省拥有四个河流流域:瓜德罗普岛、法属圭亚那、马提尼克岛和留尼汪到。依据第二部《环境法》第L. 213-14条款,海外省新增一个新的流域,马约特岛流域。

[28] 这些机构包括国家水务委员会、国家水和水生环境办公室(ONEMA)(其任务已移交给法国生物多样性署)、水坝和水利工程常设技术委员会、沿海自然环境保护协会,以及水利部际特派团。该特派团协助环境部长协调水利部门的各个部委。

[29] 6 个水务局所在省的省长担任流域协调员。

[30] 为制定水资源开发和管理总体规划而划定流域或流域组别的2005 年 5 月 16 日法令,JORF, No. 113, 17 May 2005, p. 8556.

[31] 自 2016 年 8 月 9 日《生物多样性、自然和景观重建法》颁布以来,国会议员(一名众议员和一名参议员)一直是该组织成员。

[32] 在海外各省,2016 年 8 月 9 日颁布的《生物多样性、自然和景观重建法》将流域委员会更名为水和生物多样性委员会。

[33] 在海外各省,水利委员会取代了水务局。原则上,为海外省设立的系统与为法国本土设立的系统基本相同。

[34] 《环境法》第 L. 213-8 条。

[35] 根据《环境法》第 L.211-1 条规定,”湿地是指无论是否被开发利用,通常被淡水、盐水 或咸水或永久或临时淹没的土地”。这些区域在 SDAGE 中进行了划定,例如,可能与 “自然 2000 ”网络覆盖的区域相吻合。

[36] 《环境法》第 L. 213-10 条。

[37] DROBENKO B., (2007), Droit de l’eau, Gualino, Paris, p. 269.

[38] 《环境法》第 L. 212-4 条。

[39] 《环境法》第 L. 213-12 条。

[40] P. Daillier, M. Forteau, A. Pellet, Droit international public, 8ème éd., Paris, L.G.D.D.J., 2009, p. 513, 527.

[41] 联合国大会 1962 年 12 月 14 日第 1803(XVII)号决议第 1 条 “对自然资源的永久主权”;联合国大会1973 年 12 月 17 日第 3171(XXVIII)号决议第 1 条 “对自然资源的永久主权” 联合国大会 1974 年 12 月 12 日第 3281(XXIX)号决议 “各国经济权利和义务宪章 “第 2 条第 1 款。

[42] 1974 年 12 月 12 日《各国经济权利和义务宪章》第 2 条第 1 款。

[43] S. Paquerot, Le statut des ressources vitales en droit international. Essay on the concept of the common heritage of humanity, Brussels, Bruylant, 2002, p. 13.

[44] I.C.J., 25 September 1997, Case concerning the Gabcikovo-Nagymaros Project, Hungary v. Slovenia, ICJ Reports, 1997, p. 7; S. Maljean-Dubois, “Presentation of the Case” in P.-M. Eisemann, P. Pazartis (dir.), La jurisprudence de la Cour internationale de justice, Paris, Pedone, 2008, pp. 487-503.

[45] § 174.

[46] § 175.

[47] 欧洲议会和理事会 2000 年 10 月 23 日第 2000/60/EC 号指令,建立了水政策领域的共同体行动框架, OJEC, No L 327, 22 December 2000, pp. 1-73.

[48] 如地表水体和地下水体的 “良好生态状况 “或 “良好化学状况”。生态状况的合格与否是根据生物、水文形态和物理化学质量来确定的。地表水的良好化学状态是指污染物浓度不超过《水框架指令》和欧盟其他补充标准规定的环境质量标准的地表水体所达到的化学状态。实际上,水体的生态和化学状况是由生物学家和化学家来确定的。

[49] 2004 年 4 月 21 日第 2004-338 号法律,该法律纳入了欧洲议会和理事会 2000 年 10 月 23 日关于建立水政策领域共同体行动框架的第 2000/60/EC 号指令。

[50] 欧洲议会和理事会 2000 年 10 月 23 日第 2000/60/EC 号指令,该指令建立了水政策领域的共同体行动框架,OJEC, No. L 327, 22 December 2000, p. 1.

[51] EC, Public Report, (2010), L’eau et son droit, EDCE, n° 61, La Documentation française, Paris, p. 58.

[52] 例如,2006 年 12 月 12 日欧洲议会和理事会关于保护地下水免受污染和恶化的第 2006/118/EC 号指令;2007 年 10 月 23 日欧洲议会和理事会关于评估和管理洪水风险的第 2007/60/EC 号指令; 欧洲议会和理事会 2008 年 12 月 16 日第 2008/105/EC 号指令,关于水政策领域的环境质量标准,修正和废除理事会第 82/176/EEC、83/513/EEC、84/156/EEC、84/491/EEC、86/280/EEC 号指令,并修正第 2000/60/EC 号指令;理事会 2013 年 10 月 22 日第 2013/51/Euratom 号指令,就供人类饮用的水中的放射性物质规定了保护公众健康的要求。

环境百科全书由环境和能源百科全书协会出版 (www.a3e.fr),该协会与格勒诺布尔阿尔卑斯大学和格勒诺布尔INP有合同关系,并由法国科学院赞助。

引用这篇文章: CHIU Victoria (2024年3月13日), 法国水法, 环境百科全书,咨询于 2025年4月6日 [在线ISSN 2555-0950]网址: https://www.encyclopedie-environnement.org/zh/societe-zh/water-law-in-france/.

环境百科全书中的文章是根据知识共享BY-NC-SA许可条款提供的,该许可授权复制的条件是:引用来源,不作商业使用,共享相同的初始条件,并且在每次重复使用或分发时复制知识共享BY-NC-SA许可声明。