共生与寄生

生物与其他生物之间有着永久的密切联系,其相互作用可以根据生物体的关联程度、这些相互作用的持续时间及其对双方的有益或有害影响来分类。所有的中间情况都存在,这形成了一个真正的连续体,其中既有需要其他生物体以养活自己的自由生物,也有生命周期完全受制于特定宿主的寄生虫。共生和寄生说明,除了极端多样化的情况外,相互作用在任何情况下对生物间的生活都至关重要,而且往往是由此构成的系统出现新特性的根源(are often at the origin of the emergence of new properties for the systems thus constituted)。例如,与每个生物体相关的微生物群正是如此。不过与健康个体相比,那些被寄生虫改变的生物体也是这种情况,寄生虫感染了它们,甚至扰乱受感染宿主的行为。

1.一些定义

生物圈内数十亿生物之间存在着相互作用和相互依赖的网络{生物圈指地球所有生态系统所在的生存空间,与存在生命的大气层、水圈和岩石圈的薄层相对应。这种动态的生存空间是由能量供应(主要来自太阳)和生物体与其环境相互作用的新陈代谢来维持。},生物圈这一层级是生物多样性概念的基础(阅读什么是生物多样性?)。这些相互作用通常是互利的,并在生物体的生理和适应环境方面发挥着至关重要的作用。例如,许多动物如果没有消化道中细菌的帮助就无法消化,大多数植物仅能通过定值在根部的真菌来利用土壤,作为回报,真菌以植物为食。[1]

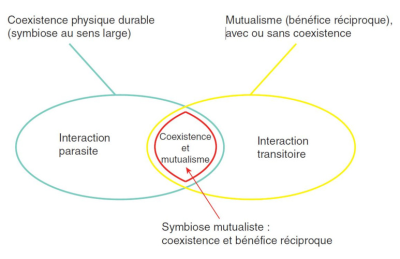

(Coexistence physique durable(symbiose au sens large) 可持续的物理共存(广义上的共生);Mutualisme(bebefice reciproque), avec ou sans coexistence 互惠主义(互惠互利),有无共存;Interaction parasite 寄生相互作用;Coexistence et mutualisme 共存与互惠;Interaction trasitoire 瞬态交互;Symbiose mutualiste: coexistence et benefice reciproque 互惠共生:共存互利)

但情况并非总是如此:两种生物之间的相互作用可以根据它们对双方的有益、有害或中性影响进行分类。因此,人们可以区分对一方有利而对另一方有害的相互作用(捕食、寄生)、对一方有利且对另一方无害的相互作用(共生)和互利的相互作用(互利共生)。所有中间情况都存在,由此形成了相互作用类型的连续体(图1)[2]。它们也可以根据它们的瞬时性(捕食)或可持续性质(寄生、互利共生等)以及共生体双方之间的关联程度进行分类[2]。在词源上,共生一词指“不同物种的生物体的共同生活”。这个广义的定义是指的是一种可持续的共存,包括两种生物的全部或部分生命周期,而不管生物间的交换。“共生”更狭义的定义仅指可持续和互惠共存(见图1红色部分)。

2.互惠共生

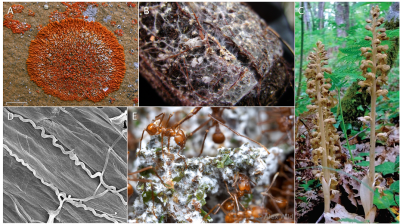

A,绿藻和子囊菌共生形成的丽石黄衣[来源:©杰森·霍林格(Jason Hollinger)@蘑菇观察者(CC BY-SA 3.0)通过Creative Commons]; B,与青云杉(棕色)根相关的外生菌根真菌的菌丝体(白色)[©安德烈-皮卡德博士(André-Ph. D. Picard)(CC BY-SA 3.0)通过Wikimedia Commons]; C,鸟巢兰,一种非叶绿素植物,利用菌根真菌和其他植物的碳[来源:©马克-安德烈·塞洛塞(Marc-André Selosse)]; D,苇状羊茅内生真菌,一种生活在高羊茅(高羊茅属)中的内共生真菌,它通过分泌对食草动物有毒的生物碱来保护其免受食草动物的侵害。[http://betterknowamicrobe.tumblr.com/post/75909408589/neotyphodium-coenophialum]; E.微小的真菌从一群大头切叶蚁身上长出蘑菇,形成白色的霉菌,生长在蚂蚁带来的叶子上。[来源: ©亚历克斯(Alex)Wild/alexanderwild.com,已获许可].

A,海葵中的小丑鱼。[来源:©尼克·霍布古德(Nick Hobgood)(CCBY-SA 3.0)通过Wikimedia Commons]; B,海葵中的共生虾岩虾[来源:©伊利斯·拉兹洛(Ilyes Lazlo) (CC BY 2.0)通过Wikimedia Commons]; C,共生型珊瑚的虫黄藻[来源:©宾夕法尼亚州立大学/弗利克(Flickr)(CC BY-NC 2.0)]; D,附着在珊瑚上的侏儒海马[来源:©约翰·西尔(John Sear)(CC BY 3.0) 通过Wikimedia Commons]

其他好处取决于其中一方的移动能力,例如蜜蜂授粉、蚂蚁或鸟类传播种子的能力。在资产负债表上,类似功能的联盟合作在进化过程中多次出现。培育真菌的昆虫(蚂蚁、白蚁、甲虫)和细胞中含有光合藻类的真核生物{单细胞或多细胞生物,其细胞有细胞核和细胞器(内质网、高尔基体、各种质体、线粒体等),并由剥膜分隔。真核生物、细菌和古细是三类生物群之一。}(例如真核细胞中出现叶绿体)的多样性说明了这种趋同(叶绿体指光合真核细胞(植物、藻类)细胞质的有机体。作为光合作用的场所,叶绿体产生氧气并在碳循环中发挥重要作用:它们利用光能固定二氧化碳并合成有机物。因此,叶绿体负责植物的自养。叶绿体是大约15亿年前光合原核生物(蓝藻型)在真核细胞内共生的结果。}(见共生和进化)。在进化过程中,所有的组织都有机会形成一种或多种互惠共生关系。对于构成微观生物生态系统的大型多细胞生物而言尤其如此。因此,根际(植物根部周围的土壤)或动物的消化道是主要的微生物生态位,每个宿主都有数千种物种,其中一些寄生对宿主有利。因此,每个生物都有一系列共生体,在多细胞生物中尤为发达。

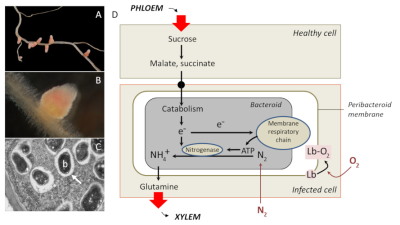

3.新兴共生特性

A,苜蓿根上的苜蓿中华根瘤菌引起的根瘤(注意粉红色,由于一种携氧蛋白质,豆血红蛋白, Lb); B,苜蓿根上由苜蓿中华根瘤菌引起的根瘤部分的视图; C,透射电子显微镜显示共生类细菌体 (b) (Bradyrhyzobium 日本慢生根瘤菌) 在大豆根瘤中,被内吞膜包围(白色箭头); D,根瘤代谢,类菌体通过受控供应来自植物的氧气和碳质底物来确保固氮. A & B: [来源:©忍者塔可壳(Ninjatacoshell)(知识共享许可协议文本,CC BY-SA 3.0)通过Wikimedia Commons]. C:[来源:©路易莎·霍华德(Louisa Howard)-达特茅斯电子显微镜设备,通过Wikimedia Commons].(图4D PHLOEM 韧皮部;Healthy cell 健康的细胞;Sucrose 蔗糖;Malate 苹果酸;succinate 琥珀酸;Peribacteroid membrane 菌周膜;Catabolism 分解代谢;Bacteroid 拟杆菌;Membrane respiratory chain 膜呼吸链;Nitrogenase 固氮酶;infected cell 被感染的细胞;Glutamine 谷氨酰胺;XYLEM 木质部)

其他特征是功能性的。在根瘤的例子中(图 4D),拟杆菌利用呼吸获得的能量,通过固氮酶{某些原核生物特有的复合酶,可催化完整的反应序列,在此过程中,二氮 N2 的还原导致氨 NH3 的形成。该反应伴随着氢化反应。}将大气中的氮 N2 还原为铵 NH3,这是植物(和拟杆菌)的氮来源。相反,植物提供碳和氧。呼吸需要氧气,但固氮酶被因氧气而失活,这一矛盾解释了为什么土壤中的游离根瘤菌{可与豆科植物共生的好氧土壤细菌。这些细菌存在于根瘤中,可以固定和减少大气中的氮,然后被植物吸收。作为交换,植物为细菌提供碳质基质。}无法固氮。另一方面,氧气不会在结节中自由扩散,而是被宿主细胞的一种蛋白质豆血红蛋白捕获[7]。豆血红蛋白位于拟杆菌周围,可保护固氮酶免受氧气的灭活作用,并为细菌呼吸提供氧气储备。因此,只能在结节内实现固氮。

共生还能诱导许多其他功能特性,例如一些依赖于诱导共生体双方防御的保护作用,共生体可以容忍这种保护作用,但对病原体是有害的。例如,菌根真菌诱导根部积累保护性单宁酸,这可以诱导整个植物(包括地上部分)提高防御和反应性水平。因此,与非菌根对照植物相比,菌根植物对食草动物或寄生虫的反应更快、更强烈。在地衣中,藻类诱导真菌合成次级代谢物,能抵御强光、保护食草动物。

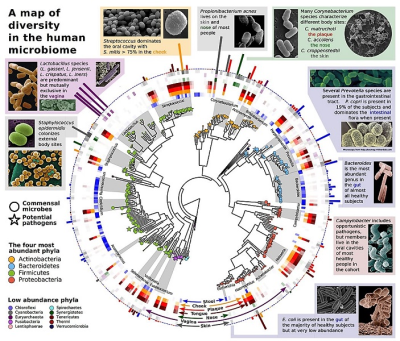

中间是代表微生物群落物种的系统发育树。在外围是特定微生物群的代表 (肠道、胃、口、阴道,等等)。[来源:从摩根(Morgan)等人复制的方案 (2013); 见参考文献[9].](A map of diversity in the human microbiome 人类微生物组多样性图;Lactobacillus species (L.gasseri,L. jensenii.L.crispatus,L. iners) are predominant but mutually exclusive in the vagina 乳酸杆菌(Lactobacillus)属(格式乳杆菌(L. gasseri),詹氏乳杆菌( L. jensenii),卷曲亚种(L.crispatus), 惰性乳杆菌(L.iners))在阴道中占优势,但是相互排斥;Streptococcus dominates the oral cavity with S.mitis > 75% in the cheek 链球菌(Streptococcus)在口腔中占主导地位,脸颊上的缓症链球菌(S.mitis)>75%;Propionibacterium acnes lives on the skin and nose of most people 痤疮丙酸杆菌(Propionibacterium acnes)存在于大多数人的皮肤和鼻子上;Many Corynebacterium species characterize different body sites:C.matruchoti the plaque C.accolens the nose C. croppenstedtii the skin 许多棒状杆菌(Corynebacterium)是不同身体部位的特征:马氏棒杆菌(C.matruchoti)是牙菌斑的特征菌,拥挤棒杆菌(C.accolens)是鼻子的特征菌,克氏棒杆菌(C. croppenstedtii)是皮肤的特征菌;Several Prevotella species are present in the gastrointestinal tract. P. copri is present in 19% of the subjects and dominates the intestinal flora when present 胃肠道中存在着几种普雷沃氏菌(Prevotella)。19%的受试者中存在着粪源普雷沃氏菌(P. copri),并在存在时支配肠道菌;Bacteroides is the most abundant genus in the gut of almost all healthy subjects 在几乎所有的健康受试者的肠道中,拟杆菌(Bacteroides)是数量最多的一个属;Campylobacter includes opportunistic pathogens,but members live in the oral cavities of most Healthy people in the cohort 弯杆菌(Campylobacter)包括机会性病原体,但其成员生活在人群中大多数健康人的口腔中;E.coli is present in the gut of the majority of healthy subjects but at very low abundance 大肠杆菌(E.coli)存在于大多数健康受试者的肠道中,但含量非常低;Staphylococcus epidermidis colonizes external body sites 表皮葡萄球菌(Staphylococcus)定植于身体外部部位;Commensal microbes 共生微生物;Potential pathogens 潜在病原体;The four most abundant phyla 最丰富的四个门;Actinobacteria 放线菌门;Bacteroidetes 拟杆菌门;Firmicutes 厚壁菌门;Proteobacteria 变形菌门;Low abundance phyla 低丰度门;Chloroflexi 绿弯菌门;Spirochaetes 螺旋体门;Cyanobacteria 蓝细菌;Synergistetes 氧菌门;Euryarchaeota 广古菌门;Tenericutes 软壁菌门;Fusobacteria 梭杆菌门;Thermi 热硫杆状菌;Lentisphaerae 黏胶球形菌门;Verrucomicrobia 疣微杆菌门;Lactobacillus 乳酸杆菌;Streptococcus 链球菌;Corynebacterium 棒状杆菌属;Actinomyces 放线菌;Bifidobacterium 双歧杆菌属;Porphyromonas 卟啉菌属;Prevotella 普雷沃氏菌属;Bacteroides 拟杆菌属;Campylobacter 弯杆菌属;Neisseria 奈瑟氏菌属;Acinetobacter 不动杆菌属;Haemophilus 嗜血杆菌属;Escherichia 埃希氏菌属;Veillonella 韦荣氏球菌属;Selenomonas 月形单胞菌属;Fusobacterium 梭杆菌属;Anaerococcus 厌氧球菌属;Clostridium 梭菌属;Ruminococcus 瘤胃球菌属;Staphylococcus 葡萄球菌;Stool 粪便;Cheek 脸颊;Plaque 牙菌斑;Tongue 舌头;Nose 鼻子;Vagina 阴道;Skin 皮肤)

总的来说,生物体的表型{指一个人可观察到的所有特征}也由其共生体产生,共生可以增加了生物体的能力或改变了生物的表型。因此,表型不仅仅是基因组编码的结果。共生体及其基因是道金斯[8]所说的“扩展表型”的一部分,即在环境中加入的、改变物种表型的一系列元素。例如,人类消化道中就含有大量细菌种类(图5):对我们肠道进行宏基因组分析,结果表明,肠道内包含近100万亿个微生物,是我们自身细胞的十倍!这就是所谓的微生物群。(见人类微生物:我们健康的盟友)

肠道微生物群{生活在动植物宿主的特定环境(称为微生物组)中的所有微生物,包含细菌、酵母菌、真菌、病毒。例如生活在肠道或肠道微生物群中的一组微生物,之前称为“肠道菌群”。}对人类身体的正常运作至关重要,不仅能帮助消化、促进维生素生成,而且在新陈代谢、免疫……或神经系统方面也发挥重要作用。人们怀疑肠道菌群不平衡是一系列病理的根源,例如肥胖、糖尿病、心血管疾病、过敏、炎症性疾病,甚至自闭症[2],[7]。人类微生物群并不局限于消化道:国际宏基因组计划已经从生活在口腔、鼻子、阴道或皮肤上的大量共生微生物中发现了基因(图5)。

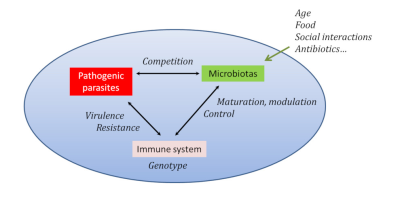

宿主基因型的作用(由蓝色椭圆表示)和所有影响微生物群组成的环境因素都会影响宿主与其寄生虫/病原体之间的相互作用,特别是通过免疫系统。[来源:改编自格洛斯(Gross)等人。见参考文献[10]](Age 年龄;Food 食物;Social interactions 社会互动;Antibiotics 抗生素;Pathogenic parasites 致病性寄生虫;Microbiotas 微生物群;Immune system 免疫系统;Competition 竞争;Maturation 成熟;modulation Control 调制控制;Genotype 基因型;Virulence 毒性;Resistance 抵抗力)

因此,有人提出,与生物学或进化相关的单元不应是生物体,而应是共生体:有人提出,与生物学或进化论相关的单位与其说是生物体,不如说是共生体:我们称其为整体生物体(holobionte),以命名这个与生物相互作用的重要性更为相关的实体。我们以全息生物{指由宿主(植物或动物)及其所有微生物组成的生物单位。}来命名这个实体,是为了让它与生物相互作用的重要性更相关。

4.寄生,一个进化的成功故事

如果共生关系中的一方发现了如何有效地利用另一方,它就变成了寄生虫。共生和寄生之间确实存在着连续性[5]。寄生虫利用另一个不相关的个体(即宿主)提供的资源,从而损害其利益。与捕食不同,寄生是与宿主的长期相互作用,这种相互作用持续时间与捕捉和消化的时间一样长。然而,从进化的角度来看,可以说捕食是寄生的一种极端形式。有些寄生虫会慢慢杀死宿主。植物寄生真菌(霉菌、蜜环菌、蹄真菌等)就是这种情况,它们在死亡的组织上完成其生命周期。当猎豹抓住一只羚羊时,会进行能量交换,而且只有能量交换。在宿主存活的宿主-寄生虫系统(称为生物营养性寄生)中,相互作用的持续时间则截然不同:两种生物体共同生活,通常一个生物在另一个体内,有时是细胞寄生在细胞内,甚至是基因组寄生在基因组内。每一方的遗传信息在一小部分空间[11]中并列且持续地表达。

所有生物作为宿主或寄生虫都会受到寄生作用的影响(图7)。在已知物种中,约200万真核生物中有30%被认为是寄生虫[12]。最著名的寄生动物{指一个有机体的所有寄生生物群。}是人类。人体包含179种寄生虫,其中35种似乎是智人[13]特有的。如果考虑超寄生(寄生虫的寄生虫),人体的寄生虫总数还要增加。超寄生是寄生节肢动物和类寄生虫{一种在“宿主”生物体上或体内发育的生物体,分为两个阶段:首先是生物营养的,然后是捕食性的,最终导致宿主死亡。}中普遍存在的现象[[14]。最近的估计表明,病毒数量被严重低估了,而病毒通过将功能转移到新生病毒颗粒来寄生到细胞中。病毒存在于所有生态系统中,是生物体中最丰富、最多样化的遗传实体[15]。

A, 缩头鱼虱(Cymothoa exigua),寄生甲壳类动物,附着在鱼的舌根上,上图是附着在大理石花纹的鱼(细条石颌鲷,Lithognathus mormyrus) 舌部[来源©马可·芬奇(Marco Vinci) (CC BY-SA 3.0),维基共享资源];

B,寄生在鱼盖(比目鱼,Platichthys flesus)上的桡足类角棘球绦虫(Acanthochondria cornuta)的卵袋,袋长约4毫米,[来源:©汉斯·希勒沃特(Hans Hillewaert),维基共享资源]; C,由德洛里欧(1831)制作的版画[16],描绘了一条绦虫(猪带绦虫,Taenia solis)); D.被寄生线虫感染的热带蚂蚁(黑门蚁,Cephalotes atratus)[来源:©史蒂夫·亚诺维克(Steve Yanoviak)/阿肯色大学,维基共享资源]; E,寄生在团藻群落中的轮虫[来源:©米歇尔·德拉鲁(Michel Delarue),生物媒介-巴黎第六大学]; F,蛹虫草(Cordyceps militaris)侵染的中国家蚕害虫柞蚕(柞蚕,Antheraea pernyi)[来源:©郑等人。参考[17]; G,被寄生真菌蝇虫霉(Entomophthora muscae)寄生的粪蝇(黄粪蝇,Scathophaga stercoraria)[来源:©汉斯·希勒沃特(Hans Hillewaert),维基共享资源]; H,被顶点线虫(nematomorphic)寄生的直翅螽斯(Anonconotus orthopter)[来源:©罗杰·德·拉格兰迪埃(Roger de La Grandière)].

与任何生物一样,寄生虫的生物特征也受到其环境施加的选择压力。寄生虫成年阶段的体型是迄今为止最重要的特征,它可以决定其他寿命或生育能力等关键特征的价值。但是,如果生长条件(寄主摄食、种内{描述属于同一物种的个体之间建立的关系的术语。}和种间{描述属于不同物种的个体之间建立的关系的术语。}竞争)不是最佳的,寄生虫可能会调整发育。此外,寄生虫的最大体型仍然受到宿主身上或内部可用空间的限制(图 7)。最后,寄生虫的成年体型通常存在性别二态性{同一物种的雄性和雌性个体之间或多或少的形态差异。}:雌性通常比雄性大得多。

5.寄生周期

寄生虫一生中为确保其繁殖而在其占据各种生态位(宿主、外部环境),寄生虫周期是其生态位转变的结果。许多寄生虫物种利用单一的宿主物种、周期简单,但另一些奇生虫则连续利用多个宿主物种:这允许季节性轮换,或增加感染形式,因为宿主定殖的成功率通常很低。周期的复杂性在进化过程中独立出现了几次。最复杂的寄生周期可以提到血吸虫(Halipegus ovocaudatus)的案例,它的周期内包括4个强制性宿主:软体动物、甲壳类桡足类、蜻蜓幼虫和青蛙。除了这些极特殊情况外,还有两至三个宿主的复杂周期,特别是在蠕虫(helminths){包括各种类型的一般寄生蠕虫的通用术语:蛔虫(线虫)、刺状树干蠕虫(棘头虫——“带刺的”蠕虫)和扁虫(扁虫:这些是线虫和吸虫)。}或锈菌(病原真菌)中。除了简单循环的复杂性外,二次简化的演化过程中也存在复杂循环。

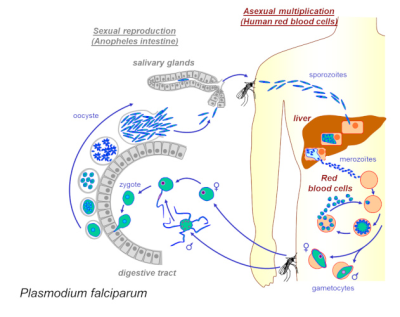

疟原虫周期(见重点)在人类(在肝脏和血液中)和蚊子(在肠道和唾液腺中)中有两个阶段[来源:©埃里克·马歇尔(Eric Maréchal)的方案].(Sexual reproduction 有性繁殖;Anopheles intestine 按蚊肠道;Asexual multiplication 无性繁殖;Human red blood cells 人体红细胞;salivary glands 唾液腺;sporozoites 孢子体;liver 肝;merozoites 裂殖孢子;Red blood cells 红细胞;gametocytes 配子体;digestive tract 消化道;zygote 受精卵;oocyste 卵囊;Plasmodium falciparum 恶性疟原虫)

感染疟原虫(Plasmodium)后,蚊子行为就会改变:它们变得更加活跃、更具攻击性并叮咬更多的人,传播的几率增加[2]。这些变化似乎与寄生虫的发育同步,例如,当寄生虫未成熟时蚊子叮咬率降低,当寄生虫达到可传播阶段时,叮咬率增加。一旦进入脊椎动物宿主体内,这些相同的寄生虫似乎能够改变宿主的气味,使它们对蚊虫更具吸引力。改变感染后宿主的行为是寄生虫操纵的一个典型例子[2]。

6.寄生虫操纵

一些寄生虫能够显著改变宿主的生理、形态或行为,从而增加其传播几率。这种利用宿主的策略现在在许多宿主-寄生虫系统{描述远距离生物之间关系分析结果的副词}中都有被描述。受感染宿主的表型{指可以分析的生物体的特征或特点,包含解剖学、生理学、分子或行为特征。}变化通常被认为是扩展表型概念的例证[18]。这些表型变化实际上对应于寄生虫基因的表达以及相应蛋白质对宿主表型的影响。根据这一观点,这些诱导的修饰是寄生虫的适应性改变,而不是宿主的适应性改变

A,瓢虫照顾瓢虫茧蜂(Dinocampus coccinellae)的幼虫。[来源:© BeatWalkerCH (CC BY-SA 3.0),维基共享资源]; B,被真菌弓背蚁僵尸真菌(Ophiocordyceps camponoti-rufipedis)寄生的巴西森林蚂蚁。[来源:©大卫·休斯(David Hughes),宾夕法尼亚州立大学]; C,来自蝴蝶尺蠖蛾的幼虫(Thyrinteina leucocerae)照顾着刻绒茧蜂(Glyptapantel)的蛹[来源:©何塞·利诺-内托(José Lino-Neto) (CC BY 2.5), 维基共享资源]; D,双盘吸虫(Leucochloridium paradoxum)感染了琥珀螺(Succinea putris)蜗牛[来源:© Studyblue 温哥华岛大学]; E,甲壳类蟹奴虫(Sacculina carcini)寄生梭子蟹(Liocarcinus holsatus)[来源:©汉斯·希勒沃特(Hans Hillewaert),维基共享资源].

一些寄生虫的操纵会导致宿主出现自杀行为。一个很典型例子是无节线虫{圆柱形的蠕虫,极其细长,平均直径为0.5-2.5毫米,长度为10-70厘米),因为给人的印象是用自己的身体打复杂的结,因此也被称为戈尔迪蠕虫。},其成虫生活在水中,看起来像一种线。宿主通常是一种陆生昆虫,例如无节线虫的幼虫寄生在蚱蜢上(图 7H)。无节线虫成虫必须返回水环境中繁殖。为此,它会操纵宿主的行为,迫使其跳入水中。由于这最后的“溺水”行为,它才能回到它完成生命周期的环境中。然而,这种类型的自杀可能对未受感染的同类动物有益,因为它降低了污染的风险。被蛇形虫草菌(Ophiocordyceps)寄生的蚂蚁正是这种情况(图 9B),它被其同类识别后,被排斥出蚁穴。

在一些涉及植物的案例中,操纵的确定性更为人所知。它揭示了病原真菌和细菌以及植物寄生线虫{圆形、不分节的蠕虫。有些蠕虫在土壤、水中等过着“自由”的生活,另一些则寄生在真菌、植物或动物体内。}中惊人的趋同机制。植物寄生线虫在根据栖息和进食、导致根部变形,称为虫瘿。这些生物的基因组编码了大量的小分泌蛋白或多肽,这些小分泌蛋白改变了其他宿主蛋白的功能。我们所说的效应蛋白是指这些细胞能够穿透宿主细胞,重组新陈代谢或改变防御反应……有时它们在细胞核水平起作用,并负责改变基因表达。这些机制很可能在其他类型的寄生中也发挥作用:它们甚至存在于菌根真菌中。这表明分泌的多肽可能有助于在互惠共生中观察到的变化,这就再次强调了互惠共生和寄生共生存在相似的机制。

除了寄生虫操纵的壮观和迷人的性质之外,所涉及的一些病原体造成了许多作物损失,而且还造成严重疾病,包括上述疟疾、登革热{全球热带和亚热带地区的蚊媒病毒感染。会导致流感样综合征,可发展为危及生命的并发症。登革热没有特殊的治疗方法。}、锥虫病{由锥虫寄生虫引起的感染}或利什曼病{如果不治疗,会导致严重致残甚至致命的皮肤或内脏疾病的一种寄生虫病。利什曼病由利什曼原虫属的各种寄生虫引起,通过俗称白蛉的昆虫叮咬传播。}等病媒传播疾病,因此构成了重大的公共卫生问题[19]。

参考文献和说明

封面照片:©黄珍妮(Jenny Huang)来自台北 (CC BY 2.0) 通过维基共享资源。

[1] Selosse M.A. (2000). La Symbiose. Vuibert, Paris.

[2] Lefèvre T., Renaud F., Selosse M.-A., Thomas F. (2010). Chapitre 14, Évolution des interactions entre espèces, in F. Thomas, T. Lefèvre & M. Raymond (ed.), Biologie évolutive, p. 555-653. De Boeck, Paris.

[3] Selosse MA, Gilbert A (2011) Des champignons qui dopent les plantes. La Recherche 457, 72-75.

[4] Selosse MA & Gilbert A (2011) Mushrooms that boost plants. Research 457, 72-75.

[5] Cleveland A., Verde E.A. & Lee R.W. (2011) Nutritional exchange in a tropical tripartite symbiosis: direct evidence for the transfer of nutrients from anemonefish to host anemone and zooxanthellae, Marine Biology, 158: 589-602

[6] Corbara B http://www.especes.org/#/1-menage-a-trois/4541755

[7] 豆血红蛋白。结构与血红蛋白非常相似的氧结合蛋白。存在于豆类的根瘤中,它保护酶复合物(固氮酶/氢化酶)免受氧气的影响,氧气会使其失活并构成细菌的氧气储备(有氧活性)。

[8] Dawkins R. (1982) The extended phenotype. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

[9] Morgan X.C., Segata N. & Huttenhower C. (2013) Biodiversity and functional genomics in the human microbiome, Trends Genet. 29, 51–58

[10] Gross R., Vavre F., Heddi A.&Hurst G.D.D., Zchori-Fein E.&Bourtzis K.(2009)Immunity and symbiosis. Molecular Microbiology 3,751-759.

[11] Selosse M.A. (2016) Au delà de l’organisme: l’holobionte. Pour la Science,269,80-84.Combes C.(1995)Interactions durables. Écologie et évolution du parasitisme. Éditions Masson,525p.

[12] From Meeûs T. & Renaud F(2002)Parasites within the new phylogeny of eukaryotes. Trends in Parasitology 18, 247-251.

[13] De Meeûs T., Prugnolle F. & Agnew P. (2009) Asexual reproduction in infectious diseases. In Lost Sex, Schön I, Martens K & van Dijk P eds, Springer, NY, p. 517-533.

[14] 寄生生物:一种在“宿主”生物体上或体内发育的生物,分为两个阶段:首先是生物营养性的,然后是捕食性的,导致宿主最终死亡。

[15] Hamilton G. (2008) Welcome to the virosphere. New Scientist 199, 38-41.

[16] 来源http://www.archive.org/stream/traitzoologiqu00brem#page/n613/mode/2up

[17] Zheng et al (2011) Genome sequence of the insect pathogenic fungus Cordyceps militaris, a valued traditional Chinese medicine. Genome Biology 12: R116

[18] Dawkins R. (1976) The selfish gene. Oxford University Press.

[19] Lefèvre T.&Thomas F(2008)Behind the scene, something else is pulling the strings: Emphasizing parasitic manipulation in vector-borne diseases. Infection, Genetics and Evolution 8,504-519.

环境百科全书由环境和能源百科全书协会出版 (www.a3e.fr),该协会与格勒诺布尔阿尔卑斯大学和格勒诺布尔INP有合同关系,并由法国科学院赞助。

引用这篇文章: SELOSSE Marc-André, JOYARD Jacques (2024年3月12日), 共生与寄生, 环境百科全书,咨询于 2024年4月18日 [在线ISSN 2555-0950]网址: https://www.encyclopedie-environnement.org/zh/vivant-zh/symbiosis-and-parasitism/.

环境百科全书中的文章是根据知识共享BY-NC-SA许可条款提供的,该许可授权复制的条件是:引用来源,不作商业使用,共享相同的初始条件,并且在每次重复使用或分发时复制知识共享BY-NC-SA许可声明。