在保护与防御之间:植物表层

PDF乔伊德·雅克,法国格勒诺布尔阿尔卑斯大学细胞与植物生理学实验室名誉主任。

大约4.5亿年前,在古生代中期,第一批在地球上定居的植物不得不面对一系列与先天的恶劣环境相关的挑战。在从水生生活方式转移到陆地生活方式的过程中,植物必须应对干燥、极端温度、重力、紫外线辐射增加等风险。它们引入了新的形态和生理特征,使它们能够在新的环境中生活。例如,现代陆生植物的特点是发展复杂的细胞壁,以提供生物力学支持和细胞结构保护。

然而,这些生物体离开水生存的最关键的适应特性当然是避免干燥的能力,即在细胞和组织内保留水分。因此,在接触空气的器官表面形成和维持疏水表层或角质层的能力可能是陆生植物进化史上最重要的创新之一。化石证据和从苔藓到开花植物的所有陆生植物中无处不在的角质层证实了这一观点[1]。

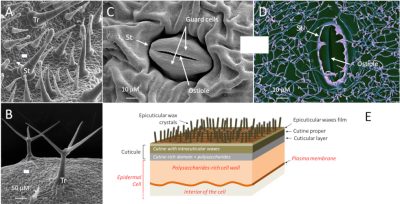

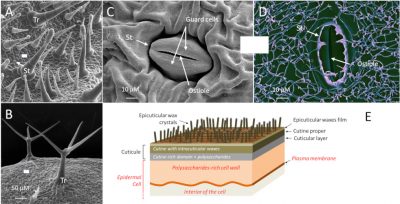

扫描电子显微镜观察(图1A-D),叶片的外表面或多或少光滑。它通常有小的卵形结构,称为气孔。它们允许植物和大气之间的气体交换,这对光合作用和呼吸作用至关重要。外观各异的毛状体(或叶面毛)主要从表面显露出来。叶面毛是一种能适应环境条件的结构,它含有萜类、酚类化合物、生物碱或其他驱避物质,在植物抵御昆虫或其他捕食者的防御反应中发挥着重要作用。

覆盖叶子的或多或少光滑的表面实际上是植物角质层的外部部分。它是覆盖所有陆生植物空气中的表皮的细胞外疏水层。角质层(图1E)根据其化学成分分为两个区域:

- 在基部,覆盖着表皮细胞的区域称为角质层。它由角质组成,富含多糖。

- 上面是角质[2]本身,富含蜡[3](它是疏水的,即排斥水)。沉积在角质基质内的蜡称为角质内蜡。在表皮上,角质被一层薄膜和表皮蜡晶所覆盖,这些蜡晶或多或少给叶子带来了明亮的外观。

由于角质层的疏水特性,它为叶子提供了对抗干燥和外部环境压力的保护。陆生植物拥有具有保护作用的表皮和一系列获取和保存水分的适应策略,使它们能在许多干燥的环境中发展壮大起来。

许多叶子都有一个特别的特点:水倾向于像水滴一样在叶子表面运动(图2),清洁表面的颗粒和碎片。这是超疏水。这种被称为“莲花效应”的自清洁机制的有效性因物种而异,它与表皮蜡晶体[4]的丰度有关。这种观察的结果是开发有效的仿生技术材料[5]的源头,如涂料或自清洁玻璃。

角质层在很大程度上允许光合作用的活性波长通过的同时,也提供了一个非常有效的屏障,可以防止UV-B射线改变细胞结构(特别是DNA)。然而,表皮蜡晶体促进了叶片表面的光反射:有光泽的表面比其他表面反射光更多。

最后,植物角质层对病原体(如真菌)架起了一座物理屏障,至少对那些不通过气孔或伤口进入叶片的病原体是这样的。一些病原体可以将角质聚合物水解成单体,然后作为植物防御反应的激发剂。表皮蜡质在某些真菌的致病性或植物与昆虫的相互作用中也起着重要的作用[1]。

关于莲花效应的视频:

参考资料及说明

封面图片。[资料来源:© Jacques Joyard]

[1] Yeats T.H. & Rose J.K.C. (2013)植物角质层的形成和功能。植物生理学. 163, 5-20.

[2] 在过去的十年中,在理解角质层的两个主要成分角质层和角质层蜡的生物合成途径(以及编码负责它们的酶的基因)方面取得了相当大的进展。

[3] 蜡不溶于水,溶于有机溶剂。它们是脂质。

[4] Barthlott W. & Neinhuis C. (1997)《神圣莲花的纯度,或逃避生物表面的污染》。植物 202, 1-8.

[5] Bhushan B. (2012)生物启发的结构表面。朗缪尔 28, 1698-1714.

Between protection and defence: the plant cuticle

PDFJOYARD Jacques, Honorary CNRS Research Director, Laboratory of Cellular & Plant Physiology, Grenoble Alpes University.

About 450 million years ago, in the middle of the Paleozoic, the first plants to colonize the Earth had to face a set of challenges related to this a priori hostile environment. In moving from an aquatic to a terrestrial lifestyle, plants have had to cope with the risks of desiccation, extreme temperatures, gravity, increased exposure to UV radiation, etc. They have introduced new morphological and physiological characteristics that allowed them to live in this new environment. For example, the development of complex cell walls for biomechanical support and structural protection of cells characterizes modern terrestrial plants.

However, the most critical adaptive trait for the survival of these organisms out of water is certainly the ability to avoid desiccation, i.e. to retain water inside cells and tissues. Therefore, the ability to form and maintain a hydrophobic surface layer, or cuticle, on the surfaces of airborne organs is probably one of the most important innovations in the history of terrestrial plant evolution. This idea is confirmed by fossil evidence and the omnipresence of cuticles among all existing terrestrial plants, from mosses to flowering plants [1].

The more or less smooth surface covering the leaf is in fact the outer part of the plant cuticle. It is an extracellular hydrophobic layer that covers the aerial epidermis of all terrestrial plants. The cuticle (Figure 1E) is divided into two areas based on its chemical composition:

- at the base, covering the epidermal cells, a domain called the cuticular layer. Composed of cutin, it is rich in polysaccharides.

- above, the cutin [2] itself, enriched with waxes [3] (which are hydrophobic, i.e. repel water). The waxes deposited inside the cutin matrix are called intracuticular waxes. On the surface, the cutin is covered with a film and epicuticular wax crystals that give the leaf a more or less brilliant appearance.

Thanks to its hydrophobic properties, the cuticle offers the leaf protection against desiccation and external environmental stresses. Armed with protective skin and a range of adaptation strategies for water acquisition and conservation, terrestrial plants have developed in many drying environments.

While the cuticle provides a very effective barrier against UV-B rays that alter cellular structures (DNA in particular), it largely allows the active wavelengths for photosynthesis to pass through. However, epicuticular wax crystals promote the reflection of light by the leaf surface: shiny surfaces reflect light more than others.

Finally, the plant cuticle presents a physical barrier to pathogens (e.g. fungi), at least against those that do not enter the leaf via stomata or wounds. Some pathogens can hydrolyze the cutin polymer into monomers which then act as elicitors of plant defense responses. Epicuticular waxes also play an important role in the pathogenicity of certain fungi or in plant insect interactions [1].

Videos on the Lotus effect:

References and notes

Cover image. [Source: © Jacques Joyard]

[1] Yeats T.H. & Rose J.K.C. (2013) The Formation and Function of Plant Cuticles. Plant Physiol. 163, 5-20.

[2] The last decade has seen considerable progress in understanding the biosynthetic pathways (and the genes encoding the enzymes responsible for them) of the two major components of the cuticle, cutin and cuticular waxes.

[3] Insoluble in water, waxes are soluble in organic solvents. They are lipids.

[4] Barthlott W. & Neinhuis C. (1997) Purity of the sacred lotus, or escape from contamination in biological surfaces. Planta 202, 1-8.

[5] Bhushan B. (2012) Bioinspired structured surfaces. Langmuir 28, 1698-1714.