Billows below the sea surface – Internal waves

PDF

The internal temperature and salinity of the ocean are not uniform and always maintain a stable layered structure. Internal waves -which are disturbances of the pycnoclinepycnocline, in oceanography, boundary separating two liquid layers of different densities. In oceans a large density difference between surface waters (or upper 100 metres [330 feet]) and deep ocean water effectively prevents vertical currents; the one exception is in polar regions where pycnocline is absent.– exhibit larger amplitudes and lower frequencies compared to ocean surface waves due to their reduced restoring force. They are commonly generated by external disturbances along continental shelf edges or mid-ocean ridges, provided that seawater stratification and seabed topography are favorable. Internal waves occur in the form of internal tides, internal solitons, and small-scale internal waves. Internal wave activities pose safety hazards to marine structures, contribute to background noise in underwater sound channels, and act as “agitators” for deep-sea mixing. Internal wave research has been applied in many fields of marine science and engineering.

- 1. Giant underwater wave

- 2. Density stratification of the ocean

- 3. Detection and spatiotemporal distribution of internal waves

- 4. Various internal waves

- 5. Safety hazards of marine structures

- 6. Source of background noise in the underwater sound channels

- 7. Deep water mixing “agitator”

- 8. Messages to remember

1. Giant underwater wave

Since internal waves occur in the water body, it is often not easy to perceive the existence of internal waves and their activities on the surface of the ocean, which makes observation and study of internal waves shrouded in a layer of mystery.

During a 1893 Arctic expedition in the North Atlantic, F. Nansen observed that the Norwegian research ship Fram suddenly slowed down. This occurred while the ship was navigating through a region of fresh water, formed by melting ice on the upper layers, near the coast of Nordenskiöld Archipelago off Siberia. It was later found that this phenomenon was called “dead water” which can occur when a ship was sailing on the pycnoclinepycnocline, in oceanography, boundary separating two liquid layers of different densities. In oceans a large density difference between surface waters (or upper 100 metres [330 feet]) and deep ocean water effectively prevents vertical currents; the one exception is in polar regions where pycnocline is absent. as an iso-density surface. This ship needs to spend energy overcoming internal waves in the ocean, which made it difficult to move forward. It was the early discovery of internal waves [1].

In a stably stratified ocean, density increases continuously with depth. However, an ocean with a strong thermoclinean abrupt temperature gradient in a body of water such as a lake, marked by a layer above and below which the water is at different temperatures. can be approximated as consisting of two uniform-density fluid layers: a lighter top layer and a denser bottom layer. In 1847, G.G. Stokes studied interfacial waves between the two layers. In 1883, J.W.S. Rayleigh studied continuous stratified structure. As for the study of actual internal waves in nature, little progress was made over a long period of time due to the difficulty of observation.

Why is it that the same external factors causing only small disturbances on the surface of the ocean can set off huge waves in the ocean? The density difference (or gravity and buoyancy difference) in the stratified ocean is much smaller than that between the atmosphere and seawater. Consequently, the restoring force, which depends on the density difference, is significantly reduced to about 0.1% of that for surface waves. This reduction results in an increase in wave amplitude [3]. Therefore, the amplitude of the internal waves can reach up to over 100 meters, 20 to 30 times that of the surface waves. Internal wave cycles range from a few minutes to dozens of hours; wavelengths up to hundreds of meters, or even tens of kilometers, which is not uncommon. Therefore, internal waves are huge underwater waves. For the same reason, internal waves propagate slowly, with a phase speed of the order of 1 m/s, while the induced current speed can reach 2 m/s [3].

2. Density stratification of the ocean

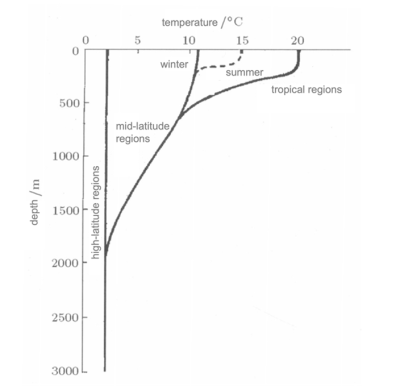

Internal waves refer to the fluctuations that occur in the stable stratified ocean and whose maximum amplitudes occur in the interior of the ocean. Understanding …. density stratified structure of the ocean is the prerequisite for exploring the mechanism of the formation of internal waves. The ocean can be broadly divided into three vertical layers. The upper mixing layer (UML), typically several dozen meters thick, is formed by wind shear and surface wave breaking. Turbulence within this layer results in a nearly uniform temperature distribution. At the seafloor, the turbulent bottom boundary layer (BBL), about 10 meters thick, is driven by flow shear. Between these two layers lies the mesosphere, a relatively calm region within the ocean interior. In this layer, weak interstitial disturbances are intermittently induced by internal waves [4].

Between the upper mixed layer and the deep water there exists a thermocline with a large temperature difference that virtually prevents the transfer of momentum, energy and mass between the upper and lower water bodies. There are two types of thermoclines as follows.

- Permanent thermocline: its depth (about 100~800 meter) and intensity do not vary with time but vary with latitude. Near the equator, the thermocline is shallower and intense; it becomes deeper and less intense at middle latitudes and then becomes shallower or even disappears in the Arctic region.

- Seasonal thermocline: it changes with time and generally occurs in summer and autumn with depths of around 100 meters (Figure 2).

The evolution of the thermocline occurs through the process of entrainment/retreat of lower ocean water into/from UML, due to external forcing such as wind stress, heating and cooling. For theoretical research, this layered structure can be approximated by a certain density model, which is often replaced by interface waves where the density gradient is large. In fact, ocean surface waves can also be regarded as a kind of “internal wave” in the Earth’s atmospheric ocean system.

With the improvement of the accuracy of detection, additional lamellar microstructures, which extend horizontally 2~20 km with thickness of 2~10 m have also been discovered in thermocline and deep water. The formation mechanism of this jagged microstructural layers has yet to be further explored. Perhaps the lamellar microstructures could be attributed to the interaction between different water masses and the breaking of small-scale internal waves.

3. Detection and spatiotemporal distribution of internal waves

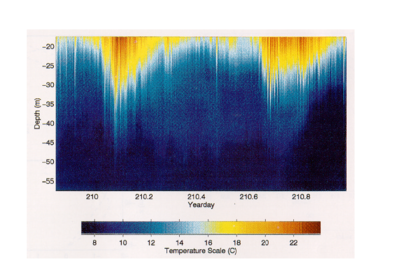

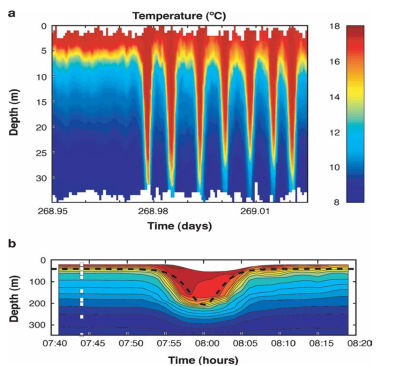

The data of isothermal surface variations can be measured by the above instruments to obtain the information of internal waves (Figure 3) [5],[6]. Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) primarily detects internal waves by exploiting the phenomena of amplitude dispersion and amplitude aggregation. Amplitude dispersion, occurring at the peaks of underwater internal waves, leads to the thinning of sea surface capillary waves, while amplitude aggregation, at the valleys, results in their densification. These processes modify the ripples and roughness of the water surface, enabling SAR to detect the traces of internal waves. Although visible light and other radars can also be used for detection, SAR is highly sensitive and unaffected by clouds and sunlight, making it the primary means of detection.

Since 1960, traces of internal waves have been successively detected in ocean waters using various new sensors, thus promoting the study of internal waves. In particular, remote sensing and on-site observation by various countries on the ERST/LAND STAT-1 space station have made it possible to map the global distribution of internal waves. It has been found that most of the internal waves often occur in marginal regions of the oceans where the stratification, topography and ocean currents are suitable, and that most of the strong thermoclines occur during the summer months. [7],[8],[9]

The ocean waters where internal waves occur can extend to as far as Bering Strait in the Arctic and the Weddel Sea in the Antarctic. There are some exceptions. For example, solitary waves can be observed north of the Azores on mid-Atlantic ridge; solitary wavelet packets can be observed northeast of the Bismark-Solomon Islands in the South Pacific using an Acoustic Doppler Current Profile meter (ADCP). The former is caused by the passage of the current of Mexico Gulf over the seafloor ridge, while the latter is attributed to the presence of sills between the Bismark-Solomon Islands. [10],[11]

4. Various internal waves

In 1834, I.S. Russell, a British scientist, observed a permanent wave rising from the water surface in front of the ship in a canal. People investigated the reason and found that the wave evolution was generated by two physical factors: the dispersion effect makes the waveform flat while the nonlinear effect renders the waveform steeper. When the two factors are balanced, the waveform remains unchanged, which is called isolated wave [8],[9],[10]. A series of isolated waves can form a wave packet, which can be modulated by wave interactions. A similar phenomenon of internal isolated waves modulated by tides can form an internal solitary wave packet as shown in Figure 3.

Tides are a significant source of disturbance for the generation of internal waves. The water bodies on Earth are continually influenced by the gravitational pull of the Moon and the Sun, resulting in the formation of tides that create powerful tidal currents. When these currents flow over seabed topography or the slopes of the continental shelf, they can disturb the pycnocline, producing a wave packet made up of a series of solitons, which is referred to as internal tides.

In the northern part of the South China Sea, several factors contribute to the prevalence of internal tides. These factors include the seasonal thermocline that develops in spring and summer, the gradually shallowing topography from southeast to northwest, and the narrow waterways in the eastern Philippines [10] [11]. The interaction between barotropic tides and the complex topography generates large waves or splits, making this region one of the most active areas for internal tides [12].

5. Safety hazards of marine structures

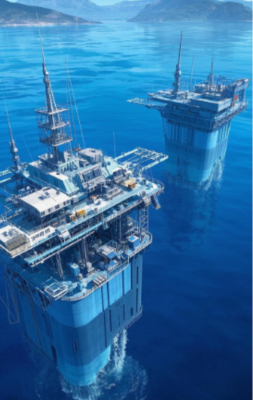

In order to meet energy needs, the first offshore platform was launched in the Mexico Bay in 1947. In the following decades, more than 1,000 offshore platforms were erected in the Gulf of Mexico, Northern Europe, West Africa, South America, the South China Sea and other waters. As water depths range from tens of meters to 3,000 meters, the platforms vary from jacket, compliant to floating (including semi-submersible, SPAR and TLP) ones (Figure 4). In the severe oceanic environment of wind, wave and current, the external loads to which the platforms are subjected must be considered for the safety of platforms and personnel in operation. The internal wave loads are one of the most significant factors [13],[14].

Previous research on internal waves only focuses on the wave motion, neglecting the analysis of its flow field. Only a few works deal with the internal wave flow field and its interaction with structures. Through the analysis of internal wave flow field, the following conclusions can be drawn: Velocity shear occurs above and below the cline. The density difference between the upper and lower layers of the cline influences its properties: a larger density difference leads to a thinner cline and stronger shear. This conclusion has been validated by observations in the Messina Channel, located in Sicily, in the Mediterranean Sea. When an internal wave propagates from a depth exceeding the critical depth to a shallower region, its solitary form transitions from convex to concave. Due to the small ratio of water depth to wavelength, the horizontal velocity within the flow field induced by the wave remains nearly uniform. This uniformity can generate substantial horizontal thrust forces, potentially causing the displacement or torsion of marine structures. When the peak of the internal wave arrives, it has an impact on the structure. In view of the characteristics of the internal wave force, the structure strength near the thermocline can be enhanced; the windward surface in the direction of the prevailing wave can be reduced; To ensure the safety of the production, the symmetry of the left and right structural design in the direction of the prevailing wind and current should be maintained as far as possible, the foundation should be strengthened, and the vibration isolation and anti-vibration engineering measures should be taken.

As for the safety of navigation, there are records of underwater vehicles falling to the bottom and being through out of the water. By analysis of the residual nucleus fragments, people concluded that the reason for the sinking was that the vehicle happened to encounter a strong internal wave when sailing in the water. The dramatic vertical force dragged it to the bottom of the ocean. The vehicle was unable to withstand the extreme pressure and then broke into pieces. Therefore, the crew of the underwater vehicle must always be alert to avoid internal waves or cline interface in front of the submarine, so as to adjust the hull balance in time and avoid accidents.

6. Source of background noise in the underwater sound channels

The absorption attenuation rate of underwater sound is 1 dB/km, which is much smaller than that of electromagnetic waves of at least 100 dB/km. Therefore, sound waves can travel farthest in water, so sound is the most favoured means of underwater detection.

The sound speed in the ocean depends on the density and pressure of seawater. The ocean’s density stratification, influenced by gradually increasing pressure, leads to a distinct stratification of sound speed. This sound speed varies depending on the season and the sea area. In general, the main thermocline, extending from the water surface to a depth of several hundred meters, exhibits a strong negative sound speed gradient. This occurs because the temperature decreases with increasing depth, leading to a corresponding reduction in sound speed. In the deep-sea isothermal layer below this layer, the seawater is in a cold and uniform stable state and the sound speed increases with growing pressure, namely with a positive sound speed gradient. Thus, around the depth where the sound speed is the minimum forms a stable deep sea sound channel. Because sound waves can be refracted and reflected in the channel, the sound waves can travel a long distance in a certain direction, and the detection distance can even exceed thousands of kilometres.

To correctly identify the target, it is necessary to understand the characteristics of the target acoustic signal, including: target reflection signal (active detection) and target radiation signal (passive detection). The target reflection signal is composed of reflection, scattering, internal reflection and induced resonance of the transmitted signal from the target mirror, which can make the transmitted signal Doppler shift, modulation and delay. And the target signal intensity and spectral characteristics can be used for identification of the target radiation signals such as mechanical noise, propeller noise, etc. Mechanical noise is superposition of strong line spectrum and weak continuous spectrum. Propeller noise is composed of blade vibration caused by water flow (KHZ and low frequency line spectrum) and cavitation noise (continuous spectrum with 100~1000Hz spectral peak). Moreover, the target signal must be extracted from the background noise and reverberation effect in the acoustic signal processing. Internal waves are an important source of background noise in the ocean, which can cause acoustic signal fluctuation strongly related to the internal wave activity up to 20dB in summer. These non-monotony declining fluctuations in amplitude and phase share the same peak position.

It can be used to explore regular and random internal wave properties. The spectrum of random internal waves in deep water discovered in the 1970s is of general significance. Because of many influencing factors in shallow water, especially the interaction between internal tides and internal solitary waves with topography, the study of internal waves in shallow water is the focus of attention of academic and engineering communities.

7. Deep water mixing “agitator”

Ocean circulation serves as a conduit for the transport of energy and materials, exerting a significant influence on global climate and marine ecosystems. It is generally understood that wind-driven circulation is responsible for the horizontal movement of ocean currents, while thermohaline circulation causes the vertical movement of currents within the meridional plane. In other words, akin to the atmospheric Hadley cell, water masses cool and become denser due to evaporation, subsequently sinking at the poles. Upon reaching the equator, they become lighter as a result of precipitation and heating, leading to their ascent. Thus, buoyancy is considered the primary driving force behind meridional overturning circulation.

Some scholars have raised doubts about this explanation. This is because most ocean circulation systems exist in a stably stratified state (with only occasional occurrences of unstable water masses on the scale of several kilometers and lasting several hours), and the configuration of heating and cooling sources differs significantly from that of Rayleigh-Bénard convection and atmospheric circulation. As early as 1916, Sandström concluded that horizontally and vertically separated cold and heat sources can only drive convection in the space between their horizontal locations if the heat source is situated below the cold source. In reality, solar heating at the equator penetrates only tens of meters, while polar cooling is confined to the surface layer. Therefore, buoyancy can only induce mixing in the surface layer. Recently, experiments by Huang Ruixin and Wang Wei have further validated Sandström’s principle. Consequently, it is essential to address the question of the energy source responsible for deep-sea mixing.

Research indicates that the energy responsible for deep-water mixing originates from wind and tides. The former contributes 20 terawatts (TW) of power to the ocean through wind stress, with 95% generating surface waves and mixed-layer turbulence, 4% driving ocean circulation, and 1% producing mesoscale eddies. The latter contributes 3.6 TW, of which 75% dissipates over continental shelves, while 25% is converted into internal tides. Geothermal heat and atmospheric pressure account for only a minor fraction of the total energy input. Previous observations have shown that only 0.1 TW of power is converted into small-scale internal waves. Considering that the destabilization of mesoscale eddies can provide an additional energy source of 0.6 TW, small-scale internal waves can allocate 0.2 TW of power to deep-water mixing. The role of internal waves as “mixers” for deep-water mixing provides a plausible explanation for the maintenance mechanism of vertical convection in the meridional plane [16]. Although many aspects of this model remain to be investigated, it fundamentally alters our understanding of ocean circulation from an energy balance perspective, thereby influencing the transport of marine materials, water masses, and heat, as well as future climate predictions.

8. Messages to remember

- Unlike the atmospheric troposphere, the ocean maintains a stable density stratification structure, and internal waves are the manifestation of pycnocline disturbances. Compared with surface waves, internal waves are characterized of larger amplitude, longer period, slower propagation and higher current speed.

- Under the external disturbance such as wind, air pressure, tides, seabed landslides and object movements, various forms of internal waves can be induced under appropriate stratified structure and terrain conditions, including micro-amplitude waves, nonlinear internal waves, solitary waves (clusters), internal wavelet package, internal tides, etc.

- Internal waves are a hidden danger to the safety of marine structures, a source of noise for underwater acoustic detection and an “agitator” for deep-sea circulation, so the study of internal waves is of great scientific and engineering significance.

Notes & references

Image de couverture. Dutch Boats in a Gale by Joseph Mallord William TURNER [Source:J. M. W. Turner, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons]

[1] Masahide Tominaga,Ocean Waves- Fundamental Theory and Observation, Science Press, Beijing,1976:423-456.

[2] Osborne AR, Burch TL. Internal solitons in the Andaman Sea. Science, 1980, 208: 451~460

[3] Tritton DJ. Physical Fluid Mechanics. Van Nostrand Reinhold Company, 1977

[4] Li JC. Turbulence in Atmosphere and Ocean. In: New Trends on Fluid Mechanics and Theoretical Physics. Peking University Press, 1993. 427~433

[5] Apers W., Heng W.C. and Lim H., Observation of internal waves in the Andaman Sea by ERS SAR in the Third ERS Symposium on Space at the Service of Our Environment Vol.3, 1997, 1287-1291.

[6] Duda TF et al. 2004, Internal tide and nonlinear wave behavior in the continental slope in the northern South China Sea. IEEE J. Ocean Eng.29:1105-31.

[7] Karl R. Helfrich & W. Kendall Melville, long nonlinear internal waves, Ann. Rev. Fluid Mech. 38, 2006. 395-425

[8] Stanton T.P et al, 1998, observations of highly nonlinear solitons over the continental shelf, Geophys. Res. Lett.25:2695-98.

[9] Jackson CR, Apel JR. An Atlas of Internal Waves and Their Properties. Global Ocean Associates, 2002

[10] Grimshaw R. Internal solitary waves. In: Liu Philip L-F, Eds. Advances in Coastal and Ocean Engineering. Vol. 3 World Scientific. 1997. 1~30

[11] Cai SQ., Gan ZJ, Long XM. Some Characteristics and evolvement of the internal solution in the northern South China Sea. Chinese Science Bulletin, 2001, 46 (15) :1245-1250

[12] Orr MH, Mignerey PC. Nonlinear internal waves in the South China Sea: observation of the conversion of depression internal waves to elevation internal waves. J. Geophys Res, 2003, 108(C3): 3064~3076

[13] Sarpkaya T, Isaacson M. Mechanics of Wave Forces on Off-shore Structures. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1981

[14] Chakrabarti SK, Fluid Structure Interaction in Offshore Engineering. Computational Mechanics Publication, 1994

[15] Caruthers JW. Elementals of Marine Acoustics. Elsevier Company, 1977

[16] Wunsch C, Ferrari R. Vertical mixing, energy and the general circulation of the oceans. Ann Review of Fluid Mech. 2004. 36: 281~304

The Encyclopedia of the Environment by the Association des Encyclopédies de l'Environnement et de l'Énergie (www.a3e.fr), contractually linked to the University of Grenoble Alpes and Grenoble INP, and sponsored by the French Academy of Sciences.

To cite this article: Li Jiachun (December 22, 2025), Billows below the sea surface – Internal waves, Encyclopedia of the Environment, Accessed January 25, 2026 [online ISSN 2555-0950] url : https://www.encyclopedie-environnement.org/en/water/billows-below-the-sea-surface-internal-waves/.

The articles in the Encyclopedia of the Environment are made available under the terms of the Creative Commons BY-NC-SA license, which authorizes reproduction subject to: citing the source, not making commercial use of them, sharing identical initial conditions, reproducing at each reuse or distribution the mention of this Creative Commons BY-NC-SA license.