高山冲积景观和生物多样性

在水陆交界处,沿河道分布的植被群落可作为部分生物的栖息地,为水、沉积物、能量与植被之间相互作用提供场所。河流动力是生态和水文地貌过程的起源,也是导致环境因子具有高时空变异性的主要原因。生物多样性在纵向上从河流源头向河口变化,横向上从开阔水域到定期被洪水淹没的回水区变化,同时生物多样性也与地下水流密切相关。在过去的两个世纪中,大多数河流都受到了人类活动干扰,由于河流对气候变化和人类活动对流域的影响高度敏感,因此导致了生物多样性受到严重破坏。目前生物多样性的恢复和管理需要依靠可持续河流动力以及河流栖息地的定期更新来完成。

1. 植物对洪水的适应性

冲积植物群落主要存在于水域和陆地环境之间的过渡区域,受河流活动影响不断地发生改变[1]。植物在外界各种约束条件下,已经形成了适应性响应,使它们能够在受水流、能量和物质流影响的栖息地中发育和繁殖[2]。植物的适应响应主要表现为:

- 高度发达的根系,能将植物牢牢固定在沉积物中,抵抗水流侵蚀;

- 能够通过埋藏在沉积物中茎和枝干再发育;

- 能够进行营养繁殖(根茎)并能通过水和风传播大量种子而迅速拓展适宜的生存环境;

- 能够适应长时间缺氧的环境。

洪水发生的频率、强度、范围和时间都是随机变化的,因此植物的适应性变化对于抵抗洪水带来的环境压力是必不可少的。河流动力变化有利于创造新的栖息地,其创造的各种各样的栖息地可以得到有效的利用,这是是形成高度生物多样性的主要原因。栖息地里柳树和杨树等植物生长和传播都与外界环境干扰有关。在洪水过后保留下的大量营养丰富的沉积物为植物发芽后的发育提供了有利的环境,并且需要在一年生物种群所需的较短时期和成熟的多年生阔叶冲积林所需的较长期间内保持稳定。

2. 河岸景观的时空组织

在平原冲积水流中,输沙泥沙的通量和粒径以及植被是主要的环境因子。植被会固定河岸,捕获沉积物(图1),然后造成大型碎屑堵塞,影响水流的分布。物理过程和生物过程之间的相互作用导致陆地和河流中栖息地的分布产生了永久性变化[1]。在这些生态系统中,如果栖息地的优势竞争物种与适应中等干扰水平的逃逸物种共存[3],其生物多样性会比较高。这些植物群落在空间上分为三个维度:

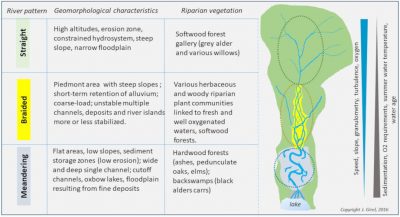

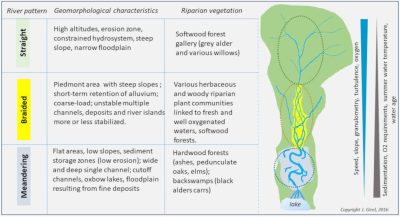

River pattern(河流类型)、Geomorphological Characteristics(地貌特征)、Riparian vegetation(河岸植被)、Straight(顺直型)、High altitudes,erosion zone,constrained hydrosystem,steep slope,narrow floodplain(高海拔,侵蚀地带,水文系统受限,坡度陡,河漫滩狭窄)、Softwood forest gallery(grey alder and various willows)针叶林(灰桤木及各种柳树);Braided (辫状河)、Piedmont area with steep slope;short-term retention of alluvium;coarse-load;unstable multiple channels,deposits and river islands more of less stabilized(山前地区有陡坡;冲积物短期滞留;荷载较粗;沟道多、不稳定,沉积物较多,河岛不稳定)、Various herbaceous and woody riparian plant communities linked to fresh and well oxygenated waters,softwood forests(各种各样的草本和木本河岸植物群落依靠淡水、含氧良好的水域,软木林);Meandering(迂回型)Flat areas,low slopes,sediment storage zones(low erosion);wide and deep single channel;cutoff channels,oxbow lakes,floodplain resulting from fine deposits(平坦地区,低斜坡,泥沙储存区(低侵蚀);宽深的单一河道;断流河道,牛轭湖,由细小沉积物形成的泛滥平原)、Hardwood forests (ashes,pedunculate oaks,elms);backswamps (black alders carrs)(平坦地区,低斜坡,泥沙储存区(低侵蚀);宽且深的单一河道;断流河道,牛轭湖,由细小沉积物形成的泛滥平原)

- 纵向分布。从河流源头到河口,水、物质和养分的供给增加;然而,河床坡度和流速减小。因此需对地貌模型进行修正(图2),在河流中段的生物多样性最高[4]。例如,在800米以下的辫状山麓地区[5],生长在白桤林下的灌木和草本植物层的物种丰度最高。

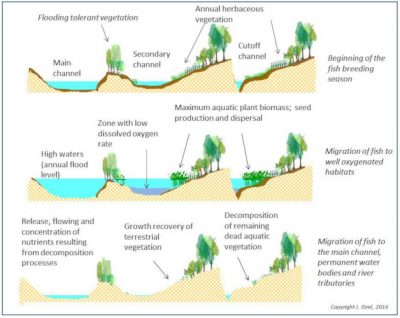

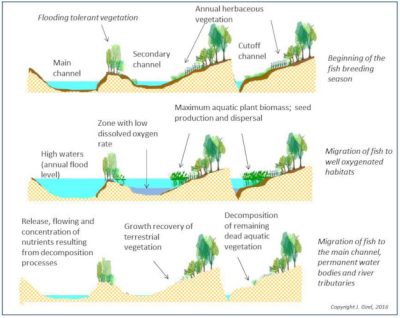

Beginning of the fish breeding season(鱼类繁殖季节开始);Main channel;flooding tolerant vegetation;Secondary channel;annual herbaceous vegetation;cutoff channel(主河道;抗洪植被;次生河道;一年生草本植被;截流河道);Migration of fish to well oxygenated habitats(鱼类迁移到含氧良好的栖息地);High waters(annual flood lever);zone with low dissolved oxygen rate;maximum aquatic plant biomass;seed production and dispersal(高水位区(年洪水位区);溶解氧率低;水生植物生物量最大;种子成熟和传播);Migration of fish to the main channel(鱼类洄游到主河道);Permanent water bodies and river tributaries:Release,flowing and concentration of nutrients resulting from decomposition processes;growth recovery of terrestrial vegetation;decomposition of remaining dead aquatic vegetation(永久水体和河流支流:分解过程中产生的营养物质的释放、流动和浓缩;陆地植被的生长恢复;残留的死亡水生植被的分解)

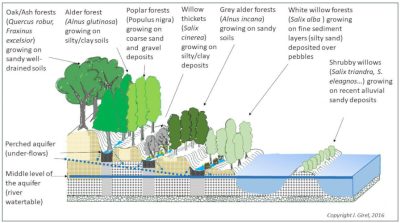

- 横向分布。水位的季节性变化导致了河道的横向动态变化,并控制冲积物的补充和养分的再分配[6](图3)。其他河道蓄水时间根据到功能性河道的距离而变化

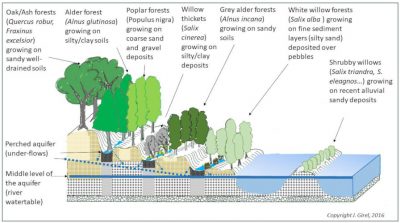

Oak/Ash forests(quercus robur,fraxinus excelsior)growing on sandy well-drained soils生长在排水良好的沙质土壤上的橡树/白蜡林(橡树,白蜡树);Alder forest(alnus glutinosa)growing on silty/clay soils 桤木林(欧洲凯木)生长在淤泥质/粘质土壤上;Poplar forests(populus nigra)growing on coarse sand and gravel deposits生长在粗砂砾层上的杨树(黑杨树);Willow thickets(salix cinerea)growing on sandy soils在沙质土壤上生长的柳树(灰柳)White willow forests(salix alba)growing on fine sediment layers(silty sand)deposition over pebbles生长在卵石上的细泥沙层(粉砂)上的白柳林;Shrubby willows(salix triandra) growing on recent alluvial sand deposits生长在新生冲积沙土上的一种灌木柳树;Perched aquifer(under-flows); middle level of the aquifer(river water table)栖居含水层(下流水位);含水层中层(河流水位)

- 垂直分布。生活在河道或陆地的物种类型取决于临时地下水的流速和深度以及永久性地下水位的变化(图4)。

此外,河岸景观仍处于可恢复重构的旧态和难以预测未来发展状态之间的过渡期。

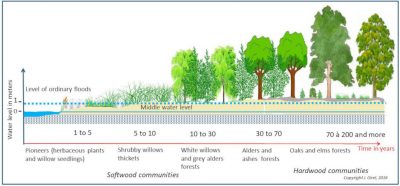

3. 生态和水文地貌过程

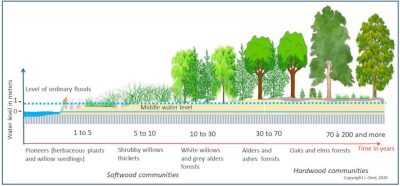

Pioneers(herbaceous plants and willow seedlings)先锋植物(草本植物及柳苗);Shrubby willows thickets柳树灌木丛;White willows and grey alders forests 白柳和赤杨树林;Alders and ashes forests赤杨和重生林;Oaks and elms forests橡树和榆树林;Water level in meters水位(米);Level of ordinary floods普通洪水水位;Middle water level中间水位;Softwood communities针叶林群落;Hardwood communities阔叶林群落

植物演替。在沉积物稳定的基础上,植被会随着时间而变化。已落位的植物物种让位给具有竞争优势的新来物种。植物群落的组成将从草本、灌丛和针叶林阶段演化到阔叶林阶段(图5)。这种演化可以用内部生态条件的变化来解释——由植物群落控制(自发演替)或由外部因素造成。外部因素所导致的变化也被称为异发演替模式,这是动态的河道中最常见的模式,因为洪水带来冲积沉积物有利于新物种的形成。在这种情况下,开始了由洪水引起并强化的异基因演替,导致了生物多样性在过渡阶段的增加。成熟阔叶林的最终阶段在真菌和细菌的参与下,在土壤中开始缓慢自发进化(图5)。

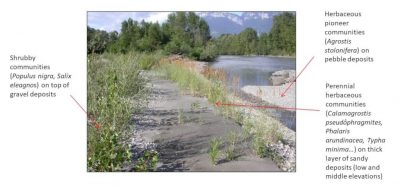

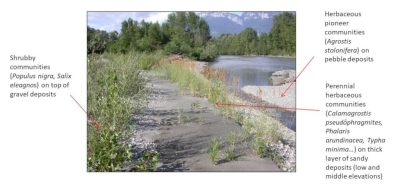

分区。河流冲刷产生的沉积物由不同比例的黏粒、粉沙、沙粒、砾石和卵石组成。它们的厚度和结构,以及地表水和地下水的特征决定了栖息地的分布状况(图4)。物种会根据当地的环境条件进行自我更替与组织。与演替一样,这些区域会突显一个或多个优势物种(图6)。

Shrubby communities(populus nigra)on top of gravel deposits砾石沉积物上的灌木群落(黑杨);Herbaceous pioneer communities(agrostis stolonifera)on pebble deposits卵石沉积物上的草本先锋群落(匍匐茎);Perennial herbaceous communitieson(Calamogrostis pesudophragmites,phalaris orundinacea)thick layer of sandy deposits(low and middle elevations)沙质沉积物厚层(中、低海拔)多年生草本群落(拟枝石竹、鹰嘴豆)

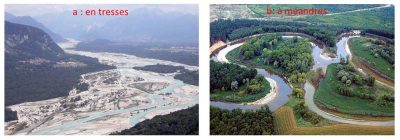

水流量,搬运负载,河流格局和植被。当水流充足,推移质丰富且可移动时,河床坡面增大,以保证向下游的运输。然而水流并不具备通过跃移来排出全部推移质的流量,因此河流床面升高。由此形成的多条河道和岛屿形成了一个交叉系统(图2、7a和8)。岛屿和河道的构成和寿命取决于洪水的强度和频率,在透水沉积物逐渐演生出各种栖息地。河道为生长快速且需氧木本植物提供了良好的栖息环境,如灰桤木、黑杨树、沙棘、德国柳和各种灌木柳。

当河道流量大、推移质少时,河道的输送能力超过了所消耗的能量时,将导致河床加深,河道延伸,坡度降低,形成弯道,洪水从悬浮物中沉淀出细小的物质。这种河流模式造就的栖息地中的植物以黑赤杨、鼠李木或灰柳等为主,这些植物逐渐适应了流速慢、含氧低的水流和紧密的土壤(图2和7b)。

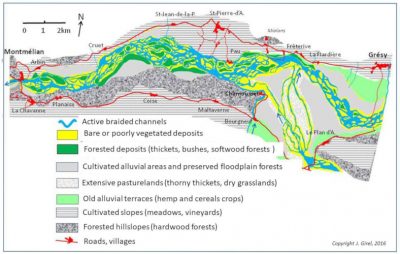

4. 人类活动的长期影响

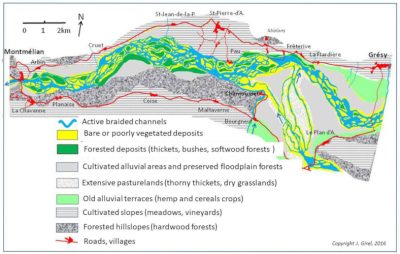

Active braided channel活跃的辫状河道;Bare of poorly vegetated deposits植被贫乏的沉积区;Forested deposits(thickets,bushes,softwood forests)森林(灌木丛、灌木丛、针叶林);Cultivated alluvial areas and preserved floodplain forests开垦的冲积地区和保护的冲积平原森林;Extensive pasturelands(thorn thickets,dry grasslands)广阔的牧场(刺灌丛,干草地);Old alluvial terraces(hemp and cereals crops)古冲积梯田(大麻和谷物作物);Cultivated slopes(meadows,vineyards)斜坡耕地(草地,葡萄园);Forested hillslopes(hardwood forests)森林山坡(阔叶林);Rods,villages道路、村庄

河型变化和生物多样性。阿尔卑斯山河流流域受气候灾害和用途变化的影响,经历了多次河型变形[7]。例如,在小冰期,降水增加、裸露山坡上侵蚀增加是山麓地区交叉分区形成的基础。由繁茂植被覆盖的岛屿和多条河道组成的辫状河景观是阿尔卑斯山景观的一个典型特征(图8),其生物多样性可能是最高的。这一假设能够在“天然”辫状河上得到验证[8],与中间扰动的假设是相吻合的[3]。

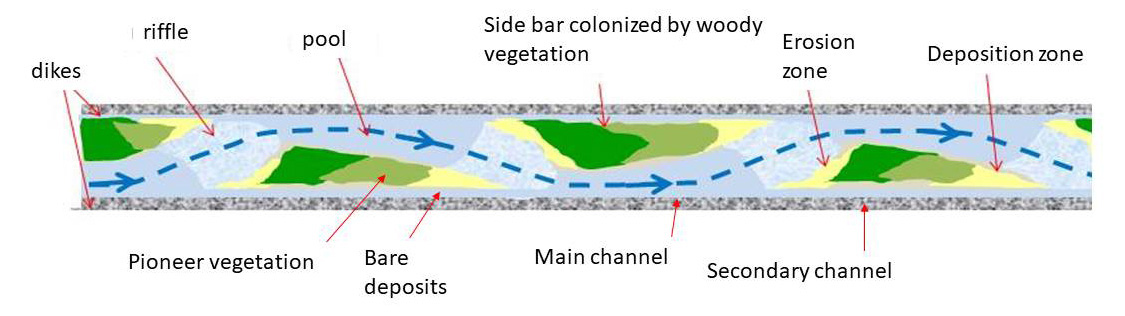

19世纪:冲积地貌结构改变。在19世纪,辫状河上建造了大量堤坝,通过引水、储水和排水工程控制流量(水、泥沙和能量),改善了河道外平原地区的洪水泛滥情况[9]。

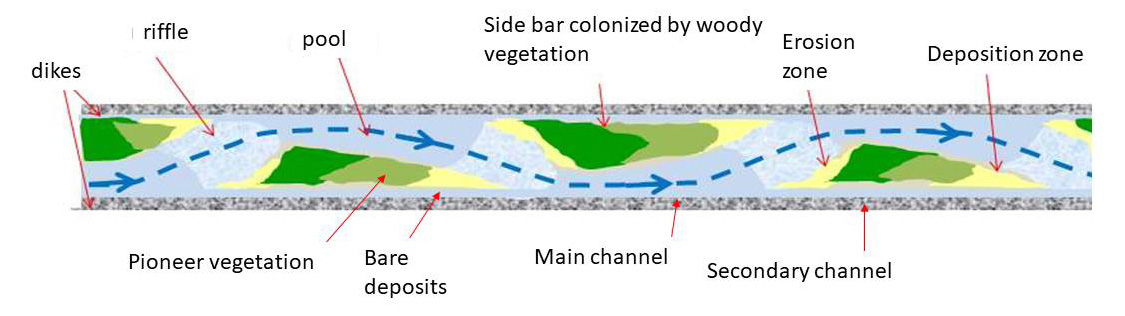

Dikes堤坝;Riffle浅滩;Pool水塘;Pioneer vegetation先锋植被;Bare deposits裸露沉积;Side bar colonized by woody vegetation被木本植被占领的侧边坝;Main channnel主河道;Secondary channel次河道; Erosion zone 侵蚀地区;Deposition zone沉积带

系统的简化[10]在景观层面影响生物多样性[11]。另一方面,在堤坝之外,碱性沼泽正在扩大。在上升的人工河床中,浅滩和水池的相继形成促使侧坝生成(图9)。这些流动的侧坝,特别是在有陡坡的河流中,通常是植物在辫状河流系统中生长的 “最后避难所”。

20世纪:生物多样性流失。20世纪初以来,流域降水减少和裸地植被化对河流动力产生了影响。山坡上减少的径流限制了侵蚀,大部分沉积物都储存在上游水力发电站中,导致河床加深,此外从河流中开采沙石更加重这种河床演变,于是出现了一种稳定的侧向沉积。现在人们常利用水坝进行储水泄洪,水坝的建造及使用进一步削弱了洪水对水文地貌的更新能力。

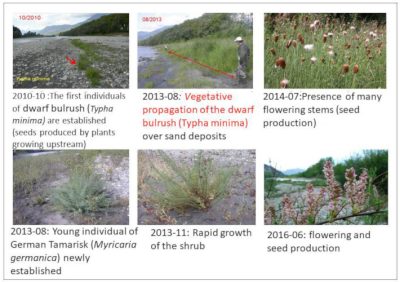

另一方面,在植物生长期间,十余年的洪水期带来了大量的沙土淤积,使河流岛屿和侧沙洲的稳定性增加,残留在植物演替末期的木本阶段的植被均质化,导致生物多样性降低。与河道相连的早期的演替植物,如矮蒲草,正面临灭绝的威胁。同样柳树(目前有六种)、德国红柳、沙棘、黑杨树和灰桤木(一种典型的高海拔山麓树种)也处于濒临灭绝的危险中。由具备自然自我更新能力的本地物种组成的结构不均的冲积群落正在被均质、稳定的优势竞争的外来物种代替。

21世纪: 河道振兴。河流岛屿和侧坝的造林绿化活动增加导致堤坝河道的通行能力降低,如发生大洪水,河道的运输能力堪忧。对高度人为改造后的冲积平原需要进行适当的干预,在允许的范围下,可以扩大流域范围,或在堤岸外的冲积林、白杨人工林或湿地和沼泽的地区建立保留地。砍伐森林和平整河道及岛屿仍然是确保人类财产安全以及保护生物多样性的必要措施。在河道内创造出裸露空间有利于提高生物丰富度,植物在这些空间内开始演替的初始阶段。不应有大型树木导致碎屑沉积物堵塞河道。

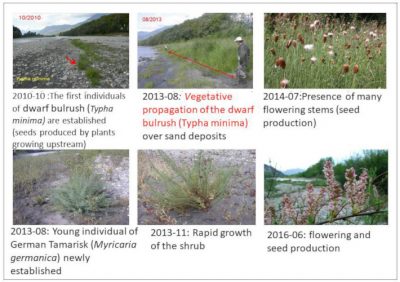

2010-10: The first individuals of dwarf bulrush are established (seeds produced by plants growing upstream) 2010年十月矮蒲草的第一批个体(生长在上游的植物产生的种子)诞生;2013-8: Vegetative propagation of the dwarf bulrush over sand deposits2013年八月矮蒲草在沙地上开始营养繁殖;2014-7: Presence of many flowering stems (seed production) 2014年七月出现有许多花茎(种子成熟);2013-8: Young individual of German Tamarisk (Myricaria germanica) newly established 2013年八月德国红柳(德国杨梅)开始生长;2013-11: Rapid growth of the shrub 2013年11月灌木迅速生长;2016-6: Flowering and seed production开花并且种子成熟

21世纪:管理河流以保护生物多样性。为确保为冲积物种创造出利于发芽、生存、繁殖、扩散的生存环境,必须要保留水流和物质流。例如,2010年5月伊泽尔河一场十年一遇的洪水重建了上一年冬天消失的侧边冲积扇。7月后黑杨树、几种柳树包括黄柳、德国红柳和各种草本植物开始生长。随着德国红柳的繁衍,黄柳这种稀有物种得到了大面积的传播(图10)。另外,由于建议让已恢复的水系统自我调节,以促进冲积地貌的定期更新,管理者可使用两种物质流:固体流(粗推移质)和液体流,但流量指标必须与水力发电厂的管理者协同进行测试。与此同时,还需要建立模型,以确定需要创建人工干扰参数,包括振幅(河道保留流量[12])、范围和具有类似自适应时间[13]。

5. 生物多样性恢复的参考状态

气候、阿尔卑斯山资源利用和辫状支流发展。在铁器时代(2700/2400 BP),后罗马时期(公元500-700 AD)和小冰期(1550-1850 )期间,阿尔卑斯山河流的粗物质运输量显著增加。主要原因包括降雨增加以及人类活动加剧,如森林砍伐和畜牧业发展。河道中的古沉积物可以很好的记录这种变化[14],这被视为辫状发育过程的起源。

古地图和参考状态的表示形式。在小冰期,山麓河流提供了与“植被覆盖型岛屿的辫状河流系统”相关的全部栖息地(约40个植物群落)。18世纪和19世纪的地图(图8和[9])所表示的多样性表明,辫状河流系统提供了阿尔卑斯山冲积平原重新发育的所有特征[15]。许多生物多样性高的地区是由于人类开发种植植物所导致的,所以回归自然状态在此存在争议[16]。此外由于社会经济方面的原因,在筑堤工程之前恢复自然生态景观是不切实际的。但研究表明,通过提升河流的空间自由度可以显着增加物种丰富度。“珠链修复理念” 的应用也证实,可以无需重建整个河道走廊就可以恢复其大部分生态潜力[17]。修复部分河流动力能实现栖息地定期更新,这些栖息地能够成为生物多样性的储存库。如阿尔克河等河流中(图11),他们确保了下游伊泽尔河的河岛上出现矮蒲草、沙棘和德国红柳等大型群落[18],另外通常生长在高海拔地区的许多物种在这里也很常见。

阿尔卑斯山冲积区生物多样性的未来。全球变暖引起的主要问题之一是水资源管理难度加大及其对河流生态的影响。如果不通过增加保留流量来恢复冲积平原生态,河岸景观的空间结构和生物多样性将有可能发生重大变化[12]。

参考资料及说明

封面图片:辫状河的植被:意大利塔利亚门托Cover image. Vegetation of a braided stream: Tagliamento, Italy. [Source: © Photo J. Girel]

[1] Concept of permanent habitat renewal in the mosaic (Shifting Habitat Mosaïc = SHM); Stanford J.A., Lorang M.S. & Hauer F.R. (2005) The shifting habitat mosaic of river ecosystems. Verhandlungen der Internationalen Vereinigung für theoretische und Angewandte Limnologie, 29, 123-136.

[2] Hauer F.R., Locke H., Dreitz V.J., Hebblewhite M., Lowe W.H., Muhlfeld C.C., Nelson C.R., Proctor M.F. & Rood S.B. (2016) Gravel-bed river floodplains are the ecological nexus of glaciated mountain landscapes. Science Advances, 2(6), 1-13.

[3] Intermediate disturbance hypothesis; Wilkinson D.M. (1999) The Disturbing History of Intermediate Disturbance. Oikos 84(1), 145-147.

[4] River Continuum Concept (RRC); Vannote R.L., Minshall G.W. & Cummins K.W. (1980) The river continuum concept. Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences, 37, 130-137.

[5] Prunier P., Bonin L. & Frossard P.-A. (2013) Guide des espèces in: Interreg France-Suisse, Programme “GeniAlp” Génie végétal en rivière de montagne, 318 pages.

[6] Flood Pulse Concept (FPC); Junk W.J., Bayley P.B. & Sparks R.E. (1989) The flood-pulse concept in river-floodplain systems. Canadian Special Publication of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences, 106, 110-127.

[7] Bravard J.-P. (2016) La longue durée des métamorphoses fluviales, in Bethemont J. & Bravard J.-P. « Pour saluer le Rhône », Ed. Libel, Lyon, 50-61

[8] Beechie T.J., Liermann M., Pollock M.M., Baker S. Davies J.R. (2006) Channel pattern and river-floodplain dynamics in forested mountain river systems. Geomorphology, 78(1-2):124-141.

[9] Girel J. (2016) La vallée de l’Isère entre Albertville et Grenoble: un paysage alluvial lié aux aménagements hydrauliques du XIXe siècle et à leurs impacts. in : P. Fournier & G. Massard-Guilbaud, (Dir), Aménagement et Environnement, Perspectives historiques, Collection “Histoire”, Presses Universitaires de Rennes, 149-161.

[10] Girel J., Garguet-Duport B. Pautou G. (1997) Present structure and construction processes of landscapes in Alpine floodplains. A case study: the Arc-Isère confluence (Savoie, France). Environmental Management, 21(6), 891-907.

[11] Girel J. (2010) Histoire de l’endiguement de l’Isère en Savoie : conséquences sur l’organisation du paysage et la biodiversité actuelle. Géocarrefour, 85(1), 2010, p. 41-54.

[12] 水力结构(大坝、堰、水力发电机组等)管理者必须为水道和生态系统的最低功能的强制保留最小水流量(以平均总流量的百分比表示)。

[13] Merritt D.M., Scott M.L., Leroy-Poff N., Auble G.T. & Lytle D.A. (2010) Theory, methods and tools for determining environmental flows for riparian vegetation: riparian vegetation-flow response guilds. Freshwater Biology, 55(1), 206-225.

[14] Salvador P.-G. (1991) La métamorphose des cours du Drac et de l’Isère à l’époque moderne dans la région grenobloise (Isère, France). Physio-Geo. (Paris), 22/23, 173-178.

[15] Ward J.V., Tockner K., Edwards P.J., Kollmann J., Bretschko G., Gurnell A., Petts G.E. & Rossaro B. (1999) A reference river system for the Alps: the “Fiume Tagliamento”. Regulated Rivers: Research & management, 15, 63-75.

[16] Girel J. (2011) Les communaux dans une vallée alpine au XIXe siècle: Impacts de l’endiguement sur le statut, la productivité et les usages des délaissés alluviaux (exemple de l’Isère dans la Combe de Savoie) in: C. Beck, J.-M. Derex & B. Sajaloli (eds), Usages et espaces communautaires dans les zones humides, Collection Journées d’études, GHZH, P. de Maisonneuve, Vincennes, 89-106. http://ghzh.free.fr/.

[17] Galat D.L., Fredrickson L.H., Humburg D.D., Bataille K.J., Bodie J.R., Dohrenwend J. et al (1998) Flooding to restore connectivity of regulated large-river wetlands. BioScience, 48, 721-733. 根据本文中提出的“串珠恢复概念”,连续扩大的冲积带(如项链中的珍珠)允许生物多样性发源地水文地貌和生态过程的正常运行。

[18] Till-Bottraud I., Poncet B.-N., Rioux D. & Girel J. (2010) Spatial structure and clonal distribution of genotypes in the rare Typha minima Hoppe (Typhaceae) along a river system. Botanica Helvetica, 120, 53-62.

环境百科全书由环境和能源百科全书协会出版 (www.a3e.fr),该协会与格勒诺布尔阿尔卑斯大学和格勒诺布尔INP有合同关系,并由法国科学院赞助。

引用这篇文章: GIREL Jacky (2024年2月23日), 高山冲积景观和生物多样性, 环境百科全书,咨询于 2024年7月27日 [在线ISSN 2555-0950]网址: https://www.encyclopedie-environnement.org/zh/vivant-zh/alpine-alluvial-landscapes-and-biodiversity/.

环境百科全书中的文章是根据知识共享BY-NC-SA许可条款提供的,该许可授权复制的条件是:引用来源,不作商业使用,共享相同的初始条件,并且在每次重复使用或分发时复制知识共享BY-NC-SA许可声明。