亚马孙:持续进化的巨型生态系统

亚马孙河地区是仅次于西伯利亚森林的世界第二大森林所在地,但在生物多样性方面却居世界第一。赤道横穿该地区,区域气候“温暖湿润”。虽受季节节律(旱季、雨季)影响,但森林总保持绿色(常绿)。包括世界第一大河——亚马孙河在内的广阔水网为其提供灌溉。从当地到全球,这一独特而复杂的区域都是许多环境、经济和社会问题的核心,涉及的问题是如此之多,以至于科学研究都投入了巨大的精力[1]。尽管如此,我们对它的了解仍然非常有限。这片森林也成为或多或少一些奇幻故事的主题:《黄金国》(Eldorado)、《绿色地狱》(Green Hell)、《翡翠森林》(emerald forest)、《地球之肺》(lung of the planet);它曾庇护着与世隔绝的人们,可怕的美洲印第安人,有时还有食人族,但事实上,他们常常是受害者,而如今被却视为和平爱好者和生态学家……人们的认知并不都是错的,但需要思考:关于这片森林,我们知道什么?我们需要获得哪些知识以及如何获得?如何利用并补充这些知识,以在这种环境下用最佳方式做出决定和采取行动?这样做有什么好处?这里的居民未来如何?

亚马孙森林生态系统在温室气体(GHGs)的调节中发挥着全球性的作用,同时也是生物多样性的宝库。此外,该生态系统蕴含的资源、居住在其中的人口及它引发的关注,使其也成为经济学、人类学和社会学的研究对象。该生态系统分布在九个国家,它的未来取决于多种政策,包括非亚马孙区域机构制定的政策。生物气候的变化可能改变其功能。人类活动可以改变其结构:从小块地的砍伐到整片区域的滥砍滥伐,或在更细微层面上的区域性改变,例如“有用”物种的增加。我们对它们的描绘和从中产生的想法,有时与现实相去甚远,但发挥着决定性作用,特别是在政治和技术决策方面。最后,自发的生物物理和生态过程使其具有高度随机的结构。例如,植物种子,尤其是树木种子,通过流体、空气和水传播,其流动通常是紊流(turbulent),或通过动物(鸟类、哺乳动物)传播,它们的运动大多是变化无常的。

1. 亚马孙森林:我们讨论的是什么?

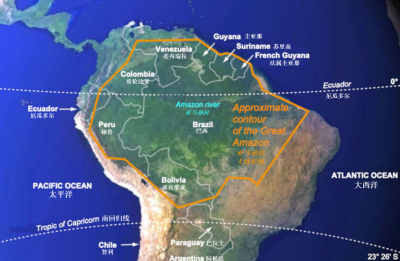

(图中,右上赤道上标注“厄瓜多尔(Ecuador)”,有误,应为“赤道(equator)”;“Approximate contour of the Great Amazon”译为“广阔亚马孙的大致轮廓”——校订者注)

“森林”一词,指的是树木茂密并占据一定陆地空间的生态系统。根据其所处的生物气候条件,森林分为不同类型。从而,我们可以区分北方针叶林、温带森林、地中海森林和热带森林。此外,还定义了森林的亚类,如温带或热带干旱和湿润森林。因此,亚马孙森林属于“热带湿润林”类型。

除了这些一般特征,在该生态系统获取的数据表现出时空的显著变异。这些变异通常是由于研究人员使用的方法和技术差别引起的。在这些计量学的变化之外,有必要加上影响生态系统动力学的生物气候和生态过程引发的变异性。人类活动也起到重要作用,在过去非常轻微和不易察觉的行为,现在可能是残忍的:大规模砍树毁林,随后焚烧。

1.1. 一片巨大的赤道空间

亚马孙森林[2]面积约550万平方公里,赤道穿过(纬度在8.5°N到20°S,经度为48°W到79°W,图1)[3],气候温暖湿润(平均气温20~30°C,最低19°C,最高35°C,年降水量2~4 m,局部1.5 m,有时6 m)。林冠*获得的光照非常重要,它有多种测量单位,最常用有光合有效辐射(photosynthetically active radiation,PAR)(考虑了光子的能量)或与其相关的光子通量密度[4]。由于植被覆盖情况不同,该通量变化很大。最多有1%入射光通量到达地面;在这一过程中,部分被捕获的光使得植被上层的附生植物*得以生长(图2)。

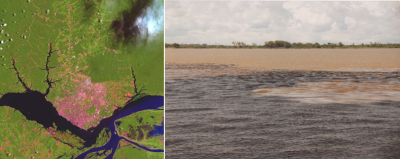

对森林动态起作用的庞大水文系统为森林排水,反之亦然。据估计,亚马孙河河口处的年平均流量在200,000~250,000 m3/s;每年流入海洋的泥沙约有10亿吨,其流域面积为679万平方公里。相当大的区域不定期会被洪水淹没而暂时形成大片湿地(图3)。

亚马孙流域降雨充沛,而且在一定程度上是自我维持的,这是蒸散*在紧挨着林冠上方形成的云所致。尽管雨来自东方,但该机制保证了距大西洋海岸2700千米的安第斯山麓也有充足的降水。云就在森林上方极低的高度形成。事实上,这些云的形成过程主要是由于树木释放的挥发性有机物(VOC)*发生光氧化使水分子聚集在亲水自由基上,而不是水蒸气在高空冷却而成。因此,水分是由森林自身维持的[5]。

1.2. “纷繁的”生态系统

查尔斯·达尔文(见焦点“达尔文”)在《物种起源》的最后一段中所用的“纷繁的”(entangled)一词,似乎很适合反映亚马孙生态系统的复杂性,就像本文最开始的照片中展示的那样。

人们对全球林分特征的了解正在日益加深:16,000个高度混杂的树种(其中227种是优势种),共计3900亿棵[6][7]。相比之下,全球树木总数估计为30400亿棵(是此前估计的4002.5亿棵的近8倍),其中热带和亚热带森林为13900亿棵,北方针叶林为7400亿棵,温带森林为6100亿棵。每年有150亿棵树被砍伐,据估计,自人类文明伊始,已有46%的树木消失[8]。显然,不同时期的估算值之间的差异不容忽视,而绝大多数关于这一主题的讨论都没有考虑到这些不确定性。此外,植被覆盖高度依赖气候条件,会随时间的推移而变化,且在冰期覆盖最小。

亚马孙生态系统包含陆地生物多样性的10%~13%,占地表生物多样性的5%[9]。目前没有对亚马孙物种数目的精确统计。对树的那项研究是个特例[10]。综合所有物种,我们可以文献中收集到的一些估计数据为基准:大约有200万物种,例如包括约4.5万种植物,约130万种动物,其中包括约100万种昆虫,约500种哺乳动物,1300种鸟和3000种淡水鱼。我们远没有鉴定出所有物种,甚至还没有对所有类群做出可靠估计[11]。如今,研究更多地聚焦于过程而非统计数量,且现在数量只是根据功能研究的需要进行估计。

1.3. 在全球环境中的作用

尽管数据波动很大,亚马孙森林生态系统是一个碳库和碳汇。据估计,地上的碳储量为1000亿吨[12]。碳储量的年际波动取决于降雨量,在干旱年份,森林与大气的碳交换平衡可能是负值,即森林吸收的温室气体少于其排放的,但只要干旱年份出现的频率保持中等,这一平衡即可在几年内得以补偿。湿地与大气之间没有明显的碳交换,湿地与河流,尤其是亚马孙河的水量大幅波动相关(图4)。

然而,太平洋的厄尔尼诺和拉尼娜事件正在迅速影响亚马孙,以至于在2010—2017年间的碳平衡为零,而根据此前的估计,这段时间的碳平衡变化极大[13]。在厄尔尼诺期间,南极绕极流的变化导致来自南极洲的干燥风增加。这些机制也许可以解释许多历史事件,如全新世的干旱期(见下文)。像这样的事件是间断出现的。

一天之中,温室气体的交换也会有变化。植物在夜间呼吸释放CO2,而白天光合作用则吸收CO2。而在季节水平上,雨季CO2的吸集比旱季更为高效。

尽管可以粗略估计出地上碳储量(见上文),但就土壤而言,由于亚马孙流域系统的规模、土壤多样性、植被覆盖、农业和其他利用,以及测量和利用结果的技术和方法等,人们面临种种困难。近年来,随着REDD(在发展中国家减少毁林和森林退化所致排放量)的实施,人类进行了巨大努力,使农业生产和土地使用情况发生了很大变化。

提出对亚马孙区域及其森林进行估计是很大胆的。我们可以引用Lucelma Aparecida Nascimento的工作[14]来简要说明结果的可变性,该工作估算森林土壤(位于马托格罗索州西北部)碳含量在0~8.89 kg/m2。这项工作包含了不同土壤和植被覆盖情况下的许多数据和分析结果。研究人员正在评估土地利用变化带来的影响,初步结果表明,草地土壤的有机碳储量高于森林的。另一方面,耕作土壤的有机碳储量则低于森林的[15]。需要指出的是,这类研究越来越使用整合分析[16]以辅助具体的实地测量工作。

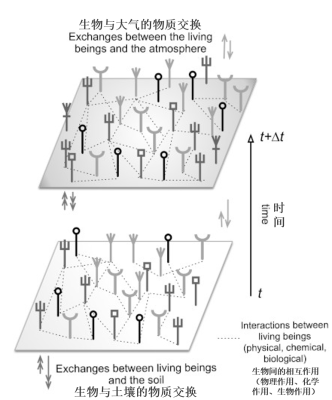

无论如何,亚马孙森林在主要的生物地球化学平衡中都发挥着重要作用。白天,像所有森林一样,它吸收二氧化碳并释放氧气(由于光合作用)。夜间,它通过呼吸作用“吸入”氧气并释放二氧化碳。它还不断释放其他气态化合物:NOx、挥发性有机物(VOCs),等等。它主要利用树木储碳,有助于在区域水平上维持湿润气候。然而,它绝不是“地球之肺”,也不是主要产氧者,其他森林和草原,特别是海洋,都对地球的氧气量有贡献。后文将提到,亚马孙森林生产了包括木材(一种长期的碳储存方式!)在内的可利用的可再生资源。最先担心该产出的维持甚至发展的,是这片森林的居民。在讨论“全球作用”(见第3小节)前,我们应该先谈谈他们。

1.4. 历史

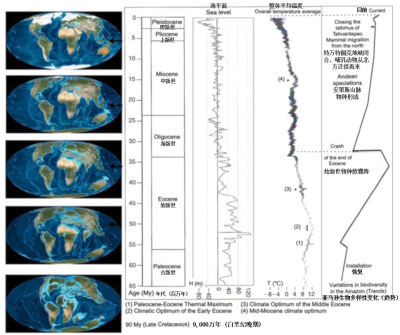

((1) 古新世-始新世极热事件(2) 早始新世气候适宜期 (3) 中始新世气候适宜期 (4) 中中新世气候适宜期)

据估计,亚马孙森林的形成始于5500万年前,即在始新世中期(图5)。其生物多样性在该期末(距今约3700万年)达到顶峰[17]。那时,全球平均气温比现在高10~12℃[18],但气温高出的幅度各地分布并不均匀,尤其是在亚马孙区域,那里的气温比现在高大约5℃[19]。两极几乎没有或根本没有冰,山上几乎没有或根本没有冰川。300万年前巴拿马地峡关闭,使得大型捕食者从北向南迁徙,这解释了在更新世-上新世过渡期前后生物多样性的下降。

在末次冰期,亚马孙森林似乎很好地抵御了干旱。过去一万年(全新世),气候和森林覆盖情况显著变化,这些变化出现于距今10,000-8,000年、距今6,000-4,000年和更近的距今1,500-1,100年和距今800-500年[20][21][22]。

2. 亚马孙森林的结构和功能

这片森林与法国的森林等其他众所周知的森林不同:

自然更新VS人类主导的更新;

生物气候带(热带VS温带);

生物多样性高(1公顷圭亚那森林平均有200个乡土树种,超过整个法国本土的树种总和:在5,500万公顷上有137个树种);

规模差异巨大(数十亿公顷VS最多数千公顷)等;

下面介绍的内容提供了更多的信息,同时也知道主要的基本生态机制是存在的。

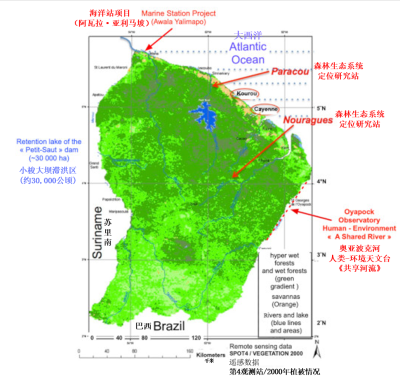

(极湿润与湿润雨林:绿色渐变区,热带稀树草原:橙色区,河流与湖泊:蓝色线条和区域)

树木分布具有高度随机性、异质性和混杂性:相邻个体通常属于不同物种(每公顷有至少1个个体为代表的,多达200个物种)。显然,这样的结构有利于增强其恢复力和生物多样性的维持[23]。这一点在森林样地,如法属圭亚那[24]的帕拉库[25]和努里格森林生态系统定位研究站的研究中可以观察到。在更大尺度上,依照大陆腹地距海洋的远近,尤其是能反映森林类型的降雨,从航空和卫星传感影像中可以看到异质性(图6)[26][27]。

在这些总体框架下,生物间存在多种生态关系,例如,树木间的竞争(获取光照和水资源)、动物的捕食、树木与动物在传播种子过程中的合作或树木之间共享菌根*的合作。在亚马孙流域由动物为传播媒介的植物是优势类群,共享菌根合作中,挥发性有机物的释放可作为捕食者或害虫(食木或食叶动物)到来的信号[28]。这些都提示我们,森林不止是树的集合,更是由其他植物、动物和微生物共同组成的生态系统。多种多样的实体会相互作用。

森林的自我更新为人熟知:树木破坏引起干扰后,喜阳树种*定居下来。随后,在其形成的遮盖下,一种相当喜雨的植被逐渐取代喜阳植物。这块森林重建后,虽与原来的森林不完全相同,但与相邻和破坏前林分的生物多样性接近[29]。

长期以来,亚马孙森林一直被认为是最初的*或原始的,即使不能忽略人类活动对森林结构和功能的影响,这些人类影响也是微不足道的。事实上,即使在考古文物缺失的情况下,许多观察结果还是引起了研究人员的注意,比如 “有用”物种在当地的增加或可持续的土壤转换。人类参与了这片森林的动态变化过程。根据这一观察结果,有必要重新审视原始森林或未开发森林这一概念。

3. 亚马孙流域:人类化的生态系统

[来源:图片 © Alain Pavé]

到2015年,亚马孙流域的人口数量约为2200万(约4人/km2),主要集中在城市(约占70%),但也分散在河流沿岸和广阔的森林中。尽管法属圭亚那是移民区,那里的人口同样很少:不足30万居民(人口密度约3.6人/km2,与亚马孙其他地区相当)(图7)。

考古学研究表明,人类在全新世伊始到达亚马孙区域(根据安娜·罗斯福的研究,距今约12,000年[30]),那些被称为“美洲印第安人”的土著人来自末次冰期末(距今约15,000年,所谓的晚冰期)[31]的西伯利亚-美洲大迁徙。亚马孙河流域的人类居住史阐明了南美定居模式:据说始于森林,随后继续迁徙到安第斯山脉和沿海地区。这些来自森林的人带来了“进步”[32],并为亚马孙河流域的生物多样性动态做出贡献,他们还发展出了基于“刀耕火种”的乡村农业(图8)。

事实上,要引发真正意义上的火灾,需要砍伐大片森林,然后让其干燥并燃烧。大多数情况下,火势在森林边缘停止蔓延,或由于湿度高而迅速停止蔓延。然而,人们担心大规模毁林会破坏森林自我维持的气候模式,引发森林干旱进而易发生火灾的连锁反应。

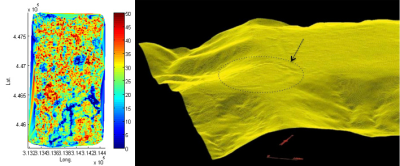

新型探测技术(见焦点“法属圭亚那与生态学新技术”)如激光雷达(激光探测及测距系统)的使用,使人们可能发现更多考古文物,并支持人类已长期定居并穿越亚马孙森林的观点(图9)[33][34]。

其中惊人的发现之一是支撑美洲印第安人农业结构的自然生态机制——800年前在沿海稀树草原上建立的“台田(raised field)”[35]。尽管处于降雨量极大的环境中,但这些结构在居民离开后依然存在(图10)。

亚马孙森林中的人既有美洲印第安人,但也有“黑棕色”血统的人,即逃出大型种植园的奴隶。那些逃脱文化渗透的人保留了非洲的知识。内河航行和建造航行所需的大型独木舟就用到了这些知识。在主要河流沿岸,还有“卡布克罗人(caboclos)”混血人群,主要是葡萄牙人和美洲印第安人通婚的后代。在那里,有欧洲血统的居民大多集中在城市区域。总的来说,人群多样性极高。

亚马孙的生物资源非常丰富。有些资源已被欧洲人利用,在亚马孙之外广受重视,比如可可、菠萝、木薯、多种豆类[36]、棕榈芯等。有许多质量很高但未充分开发的木材资源,可利用现代“可持续”提取技术对其进行干燥和加工。产乳胶的三叶胶得益于其在许多热带种植园的种植而大获成功。巴拉塔橡胶机械性能极佳,用于制造“顶级”高尔夫球。在药用方面,我们可以提到产自茜草科金鸡纳树的奎宁,该树原生于亚马孙的安第斯山脉的山坡上。然而,需要指出的是,来自森林的药用产品数目和传统医药知识有限,虽说约有1300种植物可作药用,但没有任何实质性开发。出于药理学目的的生物剽窃与其说是现实,更像是个传说。这可能并非“亚马孙的绿色黄金”[37]。

生物多样性还包括令人恐惧的病原体,特别是微生物。例如,从非洲输入的黄热病已经蔓延,在整个亚马孙流域造成了大量感染。由于其疫苗100%有效,大规模感染已不复存在,但黄热病仍然是地方性的。疟疾也是输入的,在许多地区变为地方病。南美锥虫病(chagas disease)*源于南美洲,但并不特指来自亚马孙。尽管不能穷尽亚马孙的所有病原微生物,仍然有必要提及蝙蝠传播的地方性地索美定(desmodine)*狂犬病,而蝙蝠是多种病毒的真正宿主。

环境状况是改善亚马孙地区人口健康状况的一个重要考虑因素。除病原体及病媒生物,污染也会改变环境,如淘金过程中产生的汞污染[38]。但应该指出的是,物理化学污染可通过切断污染源而阻止。如果切断污染源后污染不会逐渐减少,最坏的情况是保持不变。但可以复制并扩散的病原体却并非如此。它们还会快速演化,对包括抗生素在内的控制措施表现出抗性。生物多样性本质上并不一定是什么好事,我们的研究远远不够:剧毒的植物、危险的动物等。

包括黄金在内的矿产资源非常重要。疯狂开采破坏了当地环境,然而,绝大多数淘金活动是暗中进行的,其造成的健康和社会后果是灾难性的。另一方面,有些公司试图尽量减小破坏,并在开采后采取修复,如图11所示。巴西的卡拉加斯(Carajas)矿山(产铁和锰)与阿马帕州的塞拉都纳维(Serra do Navio)矿山都做的很不错。值得庆幸的是,曾备受威胁的伦卡(Renca)(约4.1万平方公里,位于帕拉州和阿马帕州交界处)暂时得到了保护[39]。

4. 生态学研究方法的发展

对亚马孙森林的研究已从探险模式转为生态学和人类学研究模式。探险和数据收集的第一阶段是殖民和新殖民主义背景下博物学家、地质学家、地理学家、人类学家和民族学家所做的工作[40]。随后,人们建立了野外台站。就法属圭亚那而言,从1980年代起,帕拉库和努里格(见图7)及其他一些次要台站都得以建立。与此同时,技术革命逐渐将生态学从“刀绳生态学(opinel knife ecology,piece of string)”转变为“技术生态学(technology ecology)”[41](见焦点“法属圭亚那与生态学新技术”)。之后,科学研究的结果得以高效呈现。

事关重大,森林的管理必须考虑各种目的,包括在保护居民利益的同时维持高水平的生物多样性。这种管理必须基于扎实的基础知识和多元的方法,而不仅是对单维的反映,比如严格的经济因素[42]。这样才可以为设计一个真正的生态系统工程构建完美的环境背景。

4.1. 处于非稳态中的亚马孙森林

在森林具有明显同质性的情况下,即使从很远的地方也可以利用卫星传感器区分不同林分。亚马孙森林异质性极高,非常混杂;在小尺度上,邻近树木的种类与树龄不同,因而大小不同。还可以通过土壤*(排水或不排水的土壤)和如图7(原文有错,应为图6——校订者注)所示圭亚那的陆地距海洋的远近等生物气候条件区分生态群落。亚马孙森林的年龄及历史表明其并非一成不变,而是持续变化,但以人类的时间尺度来看,这种变化非常缓慢。在这里,顶极*的概念如果没有被抛弃,那么也应该是相对的。极短时期内的观察会给人以一种平衡的错觉,从而导致自然固定不变的观念。人类活动和自然突发事件都可以暂时破坏这种状态。类似地,构成该生态系统的实体间的相互作用促进了其演化。

树木间的相互作用,树木和动物、微生物等其他生物的相互作用,或树木和仅物理化学因子的相互作用,其本质是不同的(图12)。

多样性、参与多样性的物种数目及它们的非线性相互作用使系统具有复杂性。系统中是否存在不能还原为统计平衡的“新兴”特性?这仍是个未解之谜。

4.2. 手中的机会

无论面对任何情况,仍然可以认为,随机性*和“灵活多变的”相互作用网络提升了这些森林的恢复力*。应该优先研究产生变异性进而产生多样性的过程,不仅在生态学领域如此,而且在更为广泛的生命科学领域也应如此,从而整合对“秩序与混沌生态学(ecology of order and chaos)”的争论[43]。这是可以追溯到2500年前巴门尼德和赫拉克利特争论的现代形式[44]。

即使冒着广泛宣传可能导致概念本身被消弱的风险,我们也必须在理论上做出重大努力,以推动生物多样性等方面的发展。这是包括本文作者在内的多位作者所关心的问题[45]。

最后,生物学的大部分知识都是从有限种类生物模型的基础上获得的,这些生物模型涉及的物种包括著名的果蝇和大肠杆菌在内的共约50个。有些生态系统可以为生态学发挥这种模型作用,亚马孙森林的部分或全部,就可以作为其中之一。

5. 要记住的信息

让我们回到最初在引言中提出的问题:

- 关于这片森林,我们对它了解多少?尽管人类付出了长期巨大的努力,但有关亚马孙的数据仍是零碎的、不准确的。森林并非只是树木的集合,而是树与其他动植物和微生物共同组成的生态系统,由庞大的水文系统浇灌,存在多种相互作用的。要当心过于简单化的信息和想象大于科学的描述。

- 我们需要获得哪些知识?如何获得这些知识?除实际数据外,还要对该区域进行综合、系统的描述,以指导获取环境数据,这也需要继续进行技术努力。要时刻对理论进行反思。

- 如何将这些知识在这种环境下以最佳方式用于决策和行动?建立模型以检验关于演化的设想,推广适应力强的森林物种,改进森林管理策略,建立真正的生态系统工程。

- 这样做有什么好处?这些措施首先是有利于该区居民,也有利于保护这一地区的国家,也不要忘记亚马孙生态系统,尤其是森林的全球作用(气候和生物多样性),它与全人类息息相关。

- 生活在这里的人们未来如何?(图13)这一未来必须是“合理的、精心选择的、共享的”,并通过动态管理辅以建模和仿真[46]不断重新评估和调整。

参考资料和说明

封面图片. [来源:法国国家科学研究中心,Pavé A. & Fornet G. 参考文献3]

[1] 法国的贡献主要是在法属圭亚那与其他国家(特别是巴西)的团队合作完成的。

[2] 随时间推移,人们鉴别并纠正了错误的来源。这个原因解释了估计数据的变化,550万平方公里是最小估计值。常识参考:地球表面积=5.1亿平方公里(510,067,420 km2),海洋面积=3.62亿平方公里(3.618 亿平方公里),陆地面积= 1.48亿平方公里(1.482亿平方公里),森林面积(2010)=40.33亿公顷或4003.3万平方公里(陆地面积的约27%)。

[3] Pavé A. & Fornet G., Amazonie, une aventure scientifique et humaine du CNRS, Ed. Galaade, Paris. 2010.

[4] 植物光合作用的有效辐射波长范围主要为400-700nm,被照射表面接收到的光能单位表示为µmol·m-2·s-1。

[5] U. Pöschl et al, Rainforest Aerosols as Biogenic Nuclei of Clouds and Precipitation in the Amazon. Science, 329, 2010.

[6] Stephen P. Hubbell et al. How many tree species are there in the Amazon and how many of them will go extinct? Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA, 105, supp. 1, 2008.

[7] ter Steege H. et al. Hyperdominance in the Amazonia Tree Flora. Science 342, 2013.

[8] Crowther T. W. et al. Mapping tree density at a global scale, Nature 525, 2015, 201-205.

[9] Lewinsohn T.M., Prado P.I. How many species are there in Brazil? Conserv. Biology, 19, 2005, 619-624.

[10] 事实上,这些树木仍在原地。树木很大,寿命很长。观察它们比观察更小的、会动的有机体,如动物要更容易。不过,树木也会移动,但这种移动发生在代际之间:种子扩散,然后根据当地的生物生态条件,发芽和生长可能成功或失败。这就是树木种群在生物气候变化期间迁移的方式。

[11] 事实上,在亚马孙地区经常能发现新物种。在2017年8月30日世界自然基金会(WWF)发布的报告中,鉴定出了381个新种(不包括昆虫)。

[12] Fernando D.B. Espírito-Santo et al. Size and frequency of natural forest disturbances and the Amazon forest carbon balance. Nature Communications volume 5, Article number: 3434, 2014

[13] Lie Fan et al. Satellite-observed pantropical carbon dynamics. Nature Plants, 07/29/2019. And “La biomasse aérienne de la végétation de la zone tropicale n’a plus d’impact positif sur le stockage du carbone”

[14] Nascimento L.A. Stockage du carbone dans les sols et dynamique des paysages en Amazonie : l’exemple du Nord-Ouest de l’État de Mato Grosso – Brésil dans le cadre du REDD (Réduction des Émissions par Déforestation et Dégradation).Geography. University Rennes 2, 2015. French. https://www.theses.fr/2015REN20028

[15] Fujisaki K., Perrin A. S., Desjardins T., Bernoux M., Balbino L. C. & Brossard M. (2015). From forest to cropland and pasture systems: a critical review of soil organic carbon stocks changes in Amazonia. Global Change Biology, 21 (7), 2773-2786. ISSN 1354-1013

[16] 对荟萃分析更准确的描述可以查阅:Makowski D., Synthétiser les connaissances en agronomie。Notes from the Académie d’agriculture de France, 2017. https://www.academie-agriculture.fr/publications/notes-academiques/n3af-2017-3-note-de-synthese-synthetiser-les-connaissances-en

[17] BP(距今),BC(公元前),AC(公元后)。

[18] Hoorn C. & Wesselingh F (Eds). Amazonia Lanscape and Evolution. A look into the past. Whiley-Blackwell, Oxford, UK, 2010.

[19] Randford T., Could humans cause another Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum? Climate Homenews, 2013.

[20] Schwarz D. Expansions et recul des forêts équatoriales. Pour la Science, 271, 2000. 在这篇法语文章中,我们可以找到以下两篇参考文献中介绍的大部分结果。这些结果主要来自由联合国教科文组织(UNESCO)资助、IRD/CNRS(环境项目)发起的ECOFIT“热带森林生态系统”项目。

[21] Poncy O., Sabatier D., Prévost M.F. & Hardy I. The lowland high rainforest structure and tree species diversity, in Bongers F., Charles-Dominique P., Forget P.M. & Théry M. (Eds) ” Nouragues. Dynamics and Plant-Animal Interactions in a Neotropical Rainforest”, Kluwer Acad. 2001, 32-46.

[22] Servant M & Servant-Vildary S. (Eds, 2000). Dynamiques à long terme des écosystèmes forestiers intertropicaux CNRS, UNESCO, MAE, IRD, Paris, 427p.

[23] Pavé A. Necessity of chance: biological roulettes and biodiversity, C.R. Biologies, 330, 2007, pp. 189-198

[24] 法属圭亚那面积约为84,000平方公里(接近葡萄牙的面积),其中75,000平方公里是森林(约为(法国)本土森林面积的50%)。

[25] Gourlé-Fleury S., Guehl J.M. & Laroussinie O. Ecology and Management of a Neotropical Forest. Lessons drawn from Paracou, a long-term experimental research site in French Guiana. Elsevier, 311p, 2004.

[26] Saint-Jean D. & Pellet E. Explorateurs d’Amazonie. Aventuriers de la Science en Guyane. Ibis Rouge Éditions, 2008 (Preface Alain Pavé).

[27] http://www.guyane.cnrs.fr/

[28] 人们必须谨慎使用这些最初是与人类目的有关的词语:生态系统中的竞争和合作背后并无任何目的。这些机制是自发形成的。

[29] Norten N., Angarita H. A., Bongers F., Martinez-Ramos M., Granzow-de la Cerda I., van Breugel M., Lebrija-Tejos E., Meave J.A., Vandermeer J., Bruce Williamson G., Finegan B., Mesquita R. & Chazdon R.L. Successional dynamics in neotropical forests are as uncertain as they are predictable. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA, 112, 8013-8018, 2015.

[30] 安娜·罗斯福(Anna Roosevelt)是研究亚马孙的最著名的考古学家和生态学家之一。从她的曾祖父西奥多·罗斯福(Theodore Roosevelt),这个家族就对这个地区感兴趣。西奥多曾任美国总统(1901—1909),并在两届任期后多次在亚马孙逗留。安娜有许多作品,如:Roosevelt A. Twelve Thousand Years of Human-Environment Interaction in the Amazon Floodplain. Advances in Economic Botany, Vol. 13, New York Botanical Garden. pp. 371-392, 1999. 她是法国国家科学研究中心亚马孙项目科学委员会成员。

[31] Reich D. et al. Reconstructing Native American population history. Nature, 488, 370-375, 2012. 该工作由法国国家科学研究中心亚马孙项目资助。

[32] Rostain S., Amazonie : les 12 travaux des civilisations précolombiennes. Belin, Paris, 2017; & Rostain S., Amazonie un jardin sauvage ou une force domestiquée. Essai d’écologie historique.. Actes Sud, wandering, 2011.

[33] Molino J.F., Mestre M. & Odonne G. La biodiversité de l’Amazonie, un héritage des Précolombiens ? Research, 527, 67-71, 2017.

[34] Jérémie S., Dambrine E.. Impact des occupations amérindiennes anciennes sur les propriétés des sols et la diversité des forêts guyanaises. In, Alain Pavé and Gaëlle Fornet, Op. Cit.

[35] McKey D., Rostain S., Iriarte J., Glaser B., Birk J.J., Holst I. &Renard D., “Pre-Columbian Agricultural Landscapes, Ecosystem Engineers, and Self-organized Patchiness in Amazonia”, Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA, 107, 2010, p. 7823-7828. CNRS press release, March 13, 2010.

[36] 位于哥伦比亚卡利的国际热带农业研究中心保存了约5,000个品种的活体标本。这些收藏是保持生物多样性的方式之一。

[37] 在1997年的一档电视节目中,我的态度比现要在乐观得多。在增加了20年的亚马孙经历后,我变得保守得多……获取摘录,可以点击网页:http: //www.cnrs.fr/cw/dossiers/dosbiodiv/index.php?pid=decouv_chapC_p3

[38] http://www.epoc.u-bordeaux.fr/index.php?lang=frage=eq_ea_flash01 and the summary document: https://hist-geographie.dis.ac-guyane.fr/…/2d1_les_defis_de_la_sante_en_guyane.doc

[39] 伦卡(Reserva Nacional do Cobre e Associados)于1980年代早期出于未来采矿的目的成立。在未进行开发的情况下,它实际上成了自然保护区。2017年,时任巴西总统米歇尔·特梅尔(Michel Temer)对这一状态构成威胁。面对国内外抗议,其自然保护区的状态得以保持。

[40] Raby M. The Colonial Origin of Tropical Field Station. Am. Scientist, 105, 216-223, 2017.

[41] Legay J.M. & Barbault R. (Dir.). La révolution technologique en écologie. Masson, 1995.

[42] Pavé A., Comprendre la biodiversité, vrais problèmes et idées fausses. Threshold Edition, 2019.

[43] Worster D. The Wealth of Nature, Environmental History and the Ecological Imagination. Oxford University Press, 1993.

[44] 这两位苏格拉底之前的哲学家恰巧生活在同一时期,但彼此相距甚远。巴门尼德生活在今意大利南部的埃雷,赫拉克利特生活在今土耳其西海岸的以弗所。这场辩论无疑是虚构的,是根据两位哲学家的作品及受其引导的人们的作品重新构建的。从广义上讲,用现在的话说,巴门尼德捍卫的是世界静止的观点,而观察到的运动和变化是对持续作用力的响应。赫拉克利特认为世界在不断演变(“你永远不会在同一条河中洗两次澡”),而常常是混沌动力学。这一争论无疑在思想史上留下了深刻的烙印,甚至至今仍然存在,特别是在生态学中(见上一条参考文献)。

[45] Casseta E & Delors J (Eds). La biodiversité en question. Enjeux philosophiques, éthiques et scientifiques. Editions Matériologiques, 2014, Paris.

[46] 多因子技术已证实了其有效性,尤其是在社会生态系统建模方面。伴随建模的概念似乎很适于这种情况。参见:Collectif Comod, La modélisation comme outil d’accompagnement, Natures Sciences Sociétés, 13, 165-168, 2005。从自动化工程师的工作中汲取灵感也不无道理,但令人奇怪的是,他们的工作在工业工程领域之外鲜为人知。1980年代,在罗讷-阿尔卑斯地区,里昂的生物统计学家和格勒诺布尔的自动控制专家开始合作,后合作扩展到法国国家信息与自动化研究所的爱朵拉俱乐部,合作非常有效,尤其是在建立这种合作方面非常有效。

环境百科全书由环境和能源百科全书协会出版 (www.a3e.fr),该协会与格勒诺布尔阿尔卑斯大学和格勒诺布尔INP有合同关系,并由法国科学院赞助。

引用这篇文章: PAVE Alain (2024年3月14日), 亚马孙:持续进化的巨型生态系统, 环境百科全书,咨询于 2024年4月26日 [在线ISSN 2555-0950]网址: https://www.encyclopedie-environnement.org/zh/vivant-zh/amazonia-ecosystem-constant-evolution/.

环境百科全书中的文章是根据知识共享BY-NC-SA许可条款提供的,该许可授权复制的条件是:引用来源,不作商业使用,共享相同的初始条件,并且在每次重复使用或分发时复制知识共享BY-NC-SA许可声明。