Restoring savannas and tropical herbaceous ecosystems

PDF

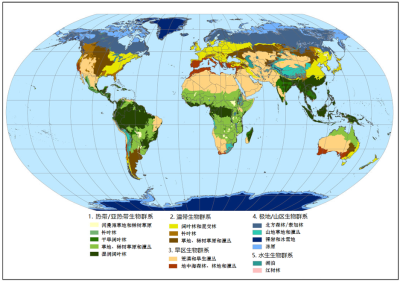

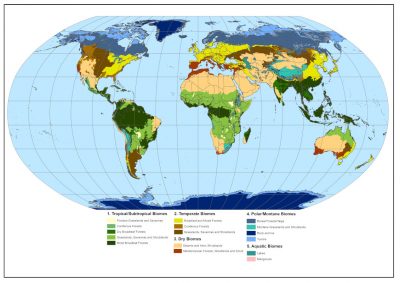

When people think of savannas, they think of the vast African landscapes where elephants, wildebeest, giraffes or lions used to roam. With the seasons, the vegetation – tall grasses more or less scattered with trees and shrubs – changes from green to yellow. These herbaceous ecosystems cover about 20% of the earth’s surface and are present throughout the world’s tropical belt, in Africa of course, but also in America and Asia. Recurrent fires or herbivores, themselves controlled by predators, keep these environments open by limiting the presence of trees and shrubs. Due to the complexity of savanna vegetation dynamics, the impacts of climate change and land use on savannas are highly uncertain. In addition, savannas are already largely threatened by human activities: conversion of land for agriculture, urbanization, etc. They are also threatened by the massive planting of trees, often implemented within the framework of carbon compensation. The natural resilience of these ecosystems to human-induced degradation is low and restoration actions are often necessary, but remain an ongoing challenge.

1. Tropical primary herbaceous ecosystems

- In Africa, in the sub-Saharan zone, in the greater East Africa region, in Central Africa and as far as South Africa (Figure 2) ;

- in South and Central America (Figure 3), mainly in the centre of the continent, in a region locally known as Cerrado, but also in Venezuela and Colombia where the savannas are known as Llanos. They also exist in the middle of the Amazon rainforest and in Guyana ;

- in northern Australia and southern New Guinea ;

- in Asia, especially in India and China, where they are less well known and cover smaller areas.

2. Organization of a savanna

2.1. Origin of savanna structure

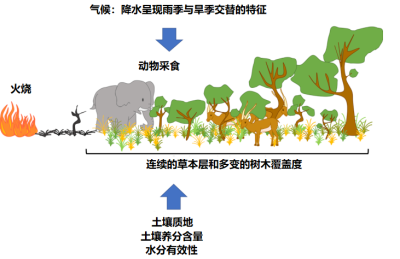

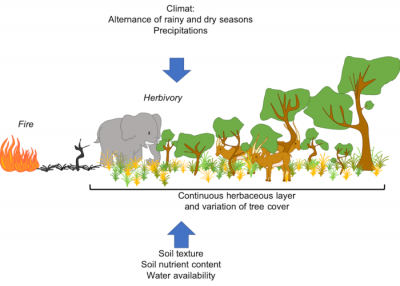

While trees are often resistant* or resilient* to fire, species in the herbaceous stratum are generally shade intolerant [2]. This coexistence is quite unusual. It is the interaction of several processes related to water use, soil properties and disturbance regimes* -such as fire- which is at the origin of the vegetation structure of these ecosystems [2],[3]:

- The climate (quantity of rainfall and length of the rainy season, among other things), since a minimum amount of rainfall is needed to allow tree to establish [4], [5], [6]. Tropical regions are characterized by a high seasonality with an marked dry and wet season [4], [6]. Many tropical areas are occupied by savannah -open ecosystems- [2], [5], [7], whereas one would expect to observe forests because of the amount of rainfall.

- chronic disturbances, including fire and herbivory, limit woody cover and thus maintain savannas (Figure 5).

- soil characteristics, such as composition and texture: sandy soil – with lower water retention – will tend to support more shrubs, while clay soil – with higher water retention – will have more herbaceous vegetation (see Figure 2).

2.2. Fire, a major player in savanna ecosystems

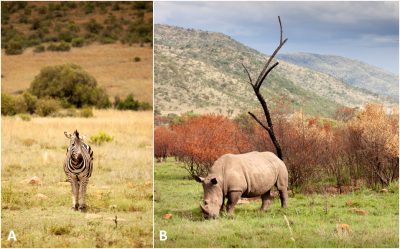

The distribution of savannas cannot therefore be predicted by climate alone. Thus, disturbances such as herbivory (especially that of “mega-herbivores”, such as elephants and ungulates) and fire play a major ecological and evolutionary role in savannas[2], [5], [9] (see Figures 2 to 5).

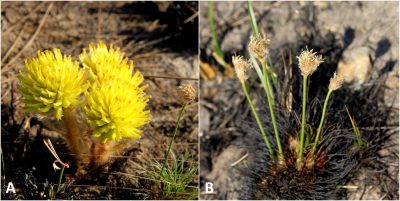

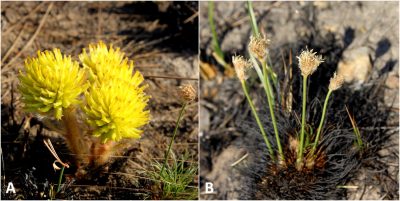

In the herbaceous stratum, grasses are a major biofuel. Their presence favours fires, limiting the growth of trees and shrubs. The life cycle of grasses, and herbaceous species in general, is well adapted to fire: they are able to regrow and reproduce very quickly following a fire (Figure 6). Their presence in these ecosystems therefore depends on the recurrence of fires.

- Savannah species exhibit traits related to fire resistance, in particular thick bark, such as Curatella americana L. (Dilleniaceae), Caryocar brasiliense (Caryocraceae), Handroanthus ochraceus (Bignoniaceae), Pterodon emarginatus (Fabaceae), Bowdichia virgilioides (Fabaceae), Annona crassiflora (Annonaceae) found in Cerrado and Llanos ;

- Forest species have much thinner bark, making them vulnerable to fire such as Copaifera langsdorffii (Fabaceae), Swartzia flaemingii (Fabaceae), Hymenaea coubaril (Fabaceae), Cariniana estrellensis (Lecythidaceae), Xylopia aromatica (Annonaceae).

In tropical regions, many savannas would be forests without the presence of these disturbances [11], as the amount of rainfall is sufficient to allow forests to occur. In these regions, forests and savannas are then considered as alternative biome states* [5], [7]. Environmental conditions allow the presence of either forest or savannah, and the presence of either state will therefore be mainly defined by the occurrence of disturbances, their intensity and frequency.

3. Biodiversity and conservation issues

Savannas represent an exceptional heritage. They are ecosystems extremely rich in biodiversity and particularly in endemic species. As an example, the Brazilian savanna called Cerrado, which extends over two million km², contains more than 12,000 plant species. It is the most species-rich savanna in the world (see Focus The Cerrado Biome).

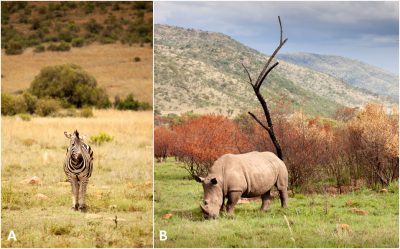

African savannas, in addition to their rich vegetation, are home to an emblematic megafauna. Elephants, zebras, giraffes, lions and cheetahs are better adapted to these open ecosystems. The savannas are also part of our cultural heritage and history. For example, some studies have shown that humans have an innate preference for open landscapes, which may stem from our long evolutionary history in the East African savannas. These environments are often considered to be one of the driving forces of human evolution.

However, human activities, even if they are not at the origin, have, over time, profoundly impacted the fire and herbivory regimes and indeed the distribution of the savannas [12]. Today many people still live at the heart of these ecosystems and depend on the services they provide, such as water quality control, grazing opportunities and the presence of game.

Despite the cultural and natural heritage they represent, tropical herbaceous ecosystems are largely threatened by the conversion of large areas for agriculture, by fire suppression policies, and by the planting of trees for commercial purposes or sometimes in the context of carbon offsetting. The Cerrado, for example, register a much higher conversion rate to agricultural land than the conversion rates recorded in the Amazonian forest [13], [14].

4. Savanna resilience

Although fires in savannas are originally natural (lightning during thunderstorms), fire regimes have long been influenced by human activities (at least 300,000 years in Africa). Human evolution is linked to an increase in burned areas [12]. The substantial impact of human activities on fire regimes, however, seems to be more recent and may date back about 4000 years. The introduction of pastoralism has been accompanied by a decrease in the surface area of burnt land: livestock grazing has reduced the amount of biofuel available [12].

The availability of nutrients in the form of ash, the presence of underground buds, the protection of buds under thick bark, or the presence of large underground organs for nutrient storage allow vegetation, whether woody or herbaceous, to grow back very quickly after a fire [5] (Figure 7).

On the other hand, in recent decades, human activities have greatly altered fire regimes, frequency and intensity, increasing the overall area burned, and changing the size of burned areas, although regional differences can be observed [12]. Many governments (e.g. Brazil, Botswana, Zimbabwe, South Africa) have established fire prevention and suppression programmes: all fires should be systematically fought and extinguished where possible.

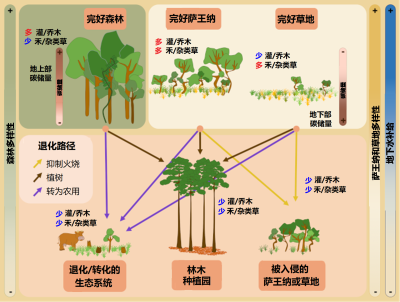

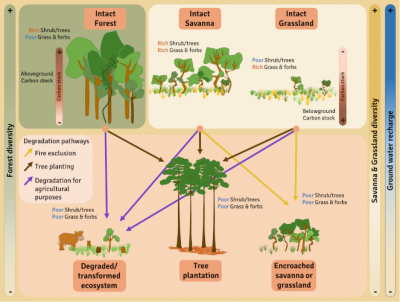

The degradation and conversion of savannas can be very rapid and often not very reversible. Degradation processes are variable, from the introduction of invasive exotic species, the introduction of livestock, the exclusion of fires, the densification of tree cover, and the planting of trees in open environments. The level of degradation obviously depends on the duration and intensity of the degradation. When disturbances are more intense, or in the case of major environmental changes such as afforestation, conversion to agricultural land or mining activities, the changes in vegetation and soil are so great that natural resilience is reduced or even non-existent [15].

Very often, the threshold of degradation beyond which spontaneous recovery of the savanna is impossible (or will take a very long time) is quickly exceeded:

- community assembly processes are slow and dependent on many interactions;

- seed dispersal is often limited.

Active restoration actions are essential in these cases.

5. Restoration of tropical herbaceous ecosystems

A first step is to take into account the natural disturbances caused by fires and large herbivores. Savanna restoration techniques therefore include the reintroduction of natural disturbances such as the use of prescribed burns, grazing management, reintroduction of herbivores, but also the elimination of invasive species.

In the case of major degradation (Figure 8), it must also be possible to restore the geomorphology and properties of the soil and then reintroduce native species, which can be complicated for most herbaceous species whose ecology and biology are poorly documented. For example, some species :

- produce few or no seeds, or do not reproduce regularly;

- depend on fire for sexual reproduction or have a dormancy that must be broken [16].

Although restoration of the herbaceous stratum is fundamental to restore the ecological processes of these ecosystems, it is often unsuccessful, often limited by :

- colonization and competition with invasive species;

- the fact that seeds of indigenous herbaceous species are not available and/or their propagation is not efficient [15].

6. Afforestation

Another problem with the restoration of savannas is that they are often misregarded as degraded forests. Their biodiversity and the importance of the (ecosystem) services they provide to societies are not always perceived by the general public and decision-makers, including government entities that might implement conservation programmes.

Often erroneously, savannas are considered degraded forests, which complicates perceptions about these ecosystems and justifies fire exclusion programs.

Thus many savannah “so-called restoration” projects involve planting trees. Mass tree planting is not an appropriate restoration technique for savannas, especially because herbaceous species, especially C4 grasses,cannot grow in shaded environments. Spontaneous regeneration of the herbaceous stratum is thus largely compromised, if not impossible, in the presence of significant tree cover.

As a result, the return to fire regimes close to natural ones, the presence of herbivores and the resulting processes will also be compromised in the absence of herbaceous biomass (food source for herbivores and fuel). Restoring the herbaceous stratum must be a priority to restore these ecosystems.

Launched in 2011, the “Bonn Challenge [17]” aims to restore 150 million hectares of degraded and deforested land by 2020 and 350 million hectares by 2030. In this context, several initiatives have emerged to promote reforestation and large-scale tree planting as a solution to climate change; trees absorb during their growth and conserve a large part of the CO2 emitted by human activities. Several initiatives have highlighted potential areas for forest restoration [18], [19]. In some cases, tree planting can have a practical objective such as combating the harmful effects of desertification and blocking the advance of the desert (see The Great Green Wall: a hope for greening the Sahel?). In this specific case, trees provides essential ecosystem services because it helps combat desertification and because the local population is highly dependent on woody biodiversity. While the existence of such projects can be welcomed when it comes to restoring degraded forests, or to meet practical objectives of combating desertification, the risk of afforesting areas where savannas and other tropical grasslands previously existed must be denounced.

Several studies have already pointed out the risk associated with tree planting in “open” ecosystems (even though tree cover can be quite high), such as savannas where the herbaceous layer is primordial and dominated by shade-intolerant species [1], [5].

It is very important to distinguish between naturally occurring savannas, which are species-rich and should be conserved, and degraded forests, sometimes erroneously called “savannas” or derived savannas, which are species-poor and can be restored to forest [21].

Moreover, if the major argument for planting trees is that it is one of the best solutions to fight climate change, it is also important to remember that in the savannas the majority of the biomass is underground, representing about 70% of the total biomass. The carbon stocks located underground are therefore far from negligible, particularly well protected from fires, and stable.

In addition to the loss of plant and animal biodiversity associated with the afforestation of these open ecosystems [22], the damage is also measurable at the economic level, especially for certain populations whose activities rely on savannas for grazing, game supply or the security of certain ecosystem services, including water supply and quality. In addition to the loss of biodiversity, habitats for many animal species and the degradation of many ecosystem services, advocating the mass planting of trees in fire-prone ecosystems increases the risk of mass fires and ultimately the loss of stored carbon (Figure 9).

7. Savannas & climate change: contrasting projections

Already greatly affected by anthropogenic land use changes, savannas are expected to be profoundly altered by climate change and rising CO2 concentrations in the atmosphere. [23] Indeed, the extent of the savannas depends on the amount of precipitation and the seasonality of the climate. For the future, contrasting projections are given by the different modelling approaches. [24] Generally speaking, climate change is tending towards a reduction in the extent of the savannahs on a global scale, according to two different mechanisms:

- In areas where reduced rainfall is predicted, there is a risk of desertification. Because the two types of vegetation that structure savannas – trees C3 and grasses C4 – respond differently to the same environmental controls, [25] savannas responses to drought may therefore be different from those of forests and grasslands [26]. Moreover, increased drought can limit the presence of trees while promoting fires in ecosystems, such as forests, that are not adapted to fire.

- In other regions, an increase in rainfall is expected, which would lead to a densification of tree and shrub cover (scrambling) to the detriment of the savannah. This process is already underway due to the increase in atmospheric CO2. [27] In some regions, a reduction in herbaceous vegetation can have serious consequences on the local economy if it depends on livestock farming and grazing, for example.

For example, climate change will lead to widespread erosion of differences between ecological communities in the Cerrado biome [28], and this will be one of the main drivers of loss of biodiversity and ecosystem services.

8. Messages to remember

- Restoration of degraded forests, including replanting trees, is essential, but tree planting should not compromise the conservation and restoration of other ecosystems.

- Ecological restoration should restore degraded ecosystems, but not destroy natural ecosystems.

- Since the restoration of savannas remains difficult, environmental policies should give priority to their conservation.

- Valuing biodiversity and recognizing the ecosystem services that savannas provide is a first step to improve their conservation, in parallel with the management of natural areas. This implies the use of prescribed burns, the presence of natural fires and/or herbivory by indigenous megafauna.

This article is a modified version of the ‘regard’ R90 by Soizig Le Stradic and Elise Buisson, published by the Société Française d’Ecologie et Evolution (SFE2) and posted on its website in February 2020.

Notes and References

Cover image. [Source : Photo © S. Le Stradig]

[1] Veldman, J.W., Buisson, E., Durigan, G., Fernandes, G.W., Le Stradic, S., Mahy, G., Negreiros, D., Overbeck, G.E., Veldman, R.G., Zaloumis, N.P., Putz, F.E., & Bond, W.J. 2015. Toward an old-growth concept for grasslands, savannas, and woodlands. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 13: 154-162.

[2] Pausas, J.G., & Bond, W.J. 2020. Alternative Biome States in Terrestrial Ecosystems. Trends in Plant Science. doi: 10.1016/d.tplants.2019.11.003.

[3] Hoffmann, W.A. 1998. Fire and population dynamics of woody plants in a neotropical savanna: matrix model projections. Ecology 80: 1354-1369.

[4] Sankaran, M., Hanan, N.P., Scholes, R.J., Ratnam, J., Augustine, D.J., Cade, B.S., Gignoux, J., Higgins, S.I., Le Roux, X., Ludwig, F., Ardo, J., Banyikwa, F., Bronn, A., Bucini, G., Caylor, K.K., Coughenour, M.B., Diouf, A., Ekaya, W., Feral, C.J., February, E.C., Frost, P.G.H., Hiernaux, P., Hrabar, H., Metzger, K.L., Prins, H.H.T., Ringrose, S., Sea, W., Tews, J., Worden, J., & Zambatis, N. 2005. Determinants of woody cover in African savannas. Nature 438: 846-849.

[5] Staver, A.C., Archibald, S., & Levin, S.A. 2011. The global extent and determinants of savanna and forest as alternative biome states. Science 334: 230-232.

[6] Lehmann, C.E.R., Anderson, T.M., Sankaran, M., Higgins, S.I., Archibald, S., Hoffmann, W.A., Hanan, N.P., Williams, R.J., Fensham, R.J., Felfili, J., Hutley, L.B., Ratnam, J., San Jose, J., Montes, R., Franklin, D., Russell-Smith, J., Ryan, C.M., Durigan, G., Hiernaux, P., Haidar, R., Bowman, D.M.J.S., & Bond, W.J. 2014. Savanna vegetation-fire-climate relationships differ among continents. Science 343: 548-552.

[7] Dantas, V. de L., Hirota, M., Oliveira, R.S., & Pausas, J.G. 2016. Disturbance maintains alternative biome states (M. Rejmanek, Ed.). Ecology Letters 19: 12-19.

[8] Vasconcelos, T.N.C., Alcantara, S., Andrino, C.O., Forest, F., Reginato, M., Simon, M.F., & Pirani, J.R. 2020. Fast diversification through a mosaic of evolutionary histories characterizes the endemic flora of ancient Neotropical mountains. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 287: 20192933.

[9] Simon, M.F., Grether, R., Queiroz, L.P. De, Skema, C., Pennington, R.T., & Hughes, C.E. 2009. Recent assembly of the Cerrado, a neotropical plant diversity hotspot, by in situ evolution of adaptations to fire. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 106: 20359-20364.

[10] Charles-Dominique, T., Beckett, H., Midgley, G.F., & Bond, W.J. 2015. Bud protection: a key trait for species sorting in a forest-savanna mosaic. New phytologist. doi: 10.1111/nph.13406; Charles-Dominique, T., Midgley, G.F., & Bond, W.J. 2017. Fire frequency filters species by bark traits in a savanna-forest mosaic (S. Scheiner, Ed.). Journal of Vegetation Science 28: 728-735.

[11] Bond, W.J., Woodward, F.I., & Midgley, G.F. 2004. The global distribution of ecosystems in a world without fire. New Phytologist 165: 525-538.

[12] Archibald, S., Lehmann, C.E.R., Gomez-Dans, J.L., & Bradstock, R.A. 2013. Defining pyromes and global syndromes of fire regimes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 110: 6442-6447.

[13] Beuchle, R., Grecchi, R.C., Shimabukuro, Y.E., Seliger, R., Eva, H.D., Sano, E., & Achard, F. 2015. Land cover changes in the Brazilian Cerrado and Caatinga biomes from 1990 to 2010 based on a systematic remote sensing sampling approach. Applied Geography 58: 116-127.

[14] Overbeck, G.E., Müller, S.C., Fidelis, A., Pfadenhauer, J. Pillar, V.D., Blanco, C.C., Boldrini, I.I., Both, R., & Forneck, E. (2007). Brazil’s neglected biome: The South Brazilian Campos. Perspectives in Plant Ecology, Evolution and Systematics. 9. 101-116. 10.1016/j.ppees.2007.07.005.

[15] Buisson, E., Le Stradic, S., Silveira, F.A.O., Durigan, G., Overbeck, G.E., Fidelis, A., Fernandes, G.W., Bond, W.J., Hermann, J., Mahy, G., Alvarado, S.T., Zaloumis, N.P., & Veldman, J.W. 2019. Resilience and restoration of tropical and subtropical grasslands, savannas, and grassy woodlands. Biological Reviews 94: 590-609.

[16] Dayrell, R.L.C., Garcia, Q.S., Negreiros, D., Baskin, C.C., Baskin, J.M., & Silveira, F.A.O. 2017. Phylogeny strongly drives seed dormancy and quality in a climatically buffered hotspot for plant endemism. Annals of Botany 119: 267-277.

[17] The Bonn Challenge is a global effort to restore 150 million hectares of deforested and degraded land worldwide by 2020, and 350 million hectares by 2030. It was launched in 2011 by the German government and IUCN and endorsed and extended by the New York Declaration on Forests at the 2014 UN climate summit.

[18] Bastin, J.-F., Finegold, Y., Garcia, C., Mollicone, D., Rezende, M., Routh, D., Zohner, C.M., & Crowther, T.W. 2019. The global tree restoration potential. Science 365: 76-79.

[19] Forest: sustaining forests for people and planent; World Resources Institute.

[20] Veldman J.W., Aleman J.C., Alvarado S.T., Anderson T.M., Archibald S. et al. 2019. Comment on “The global tree restoration potential.” Science 366, Issue 6463, eaay7976; DOI: 10.1126/science.aay7976

[21] Meli, P., Holl, K.D., Rey Benayas, J.M., Jones, H.P., Jones, P.C., Montoya, D., & Moreno Mateos, D. 2017. A global review of past land use, climate, and active vs. passive restoration effects on forest recovery (S. Joseph, Ed.). PLOS ONE 12.

[22] Abreu, R.C.R., Hoffmann, W.A., Vasconcelos, H.L., Pilon, N.A., Rossatto, D.R., & Durigan, G. 2017. The biodiversity cost of carbon sequestration in tropical savannah. Science Advances 3: e1701284.

[23] Osborne C.P., Charles-Dominique T., Stevens N., Bond W.J., Midgley G. & Lehmann C.E.R. (2018) Human impacts in African savannas are mediated by plant functional traits. New Phytologist 220:10-24.

[24] Moncrieff, G.R., Scheiter, S., Langan L., Trabucco, A. & Higgins, S.I. 2016. The future distribution of the savannah biome: model-based and biogeographic contingency. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B37120150311

[25] With the increase of CO2 concentration in the atmosphere, C3 plants could reach photosynthetic activities approaching those of C4 plants (see The path of carbon in photosynthesis).

[26] Sankaran M. (2019) Droughts and the ecological future of tropical savanna vegetation. J. Ecol. 107:1531-1549.

[27] O’Connor, T.G., Puttick, J.R. & M Hoffman, M.T. (2014) Bush encroachment in southern Africa: changes and causes, African Journal of Range & Forage Science, 31:2, 67-88, DOI: 10.2989/10220119.2014.939996

[28] Hidasi-Neto, J., Joner, D. C., Resende, F., Monteiro, L. D., Faleiro, F. V., Loyola, R. D., & Cianciaruso, M. V. (2019). Climate change will drive mammal species loss and biotic homogenization in the Cerrado Biodiversity Hotspot. Perspectives in Ecology and Conservation. doi:10.1016/j.pecon.2019.02.001

The Encyclopedia of the Environment by the Association des Encyclopédies de l'Environnement et de l'Énergie (www.a3e.fr), contractually linked to the University of Grenoble Alpes and Grenoble INP, and sponsored by the French Academy of Sciences.

To cite this article: LE STRADIC Soizig, BUISSON Elise (July 24, 2020), Restoring savannas and tropical herbaceous ecosystems, Encyclopedia of the Environment, Accessed July 27, 2024 [online ISSN 2555-0950] url : https://www.encyclopedie-environnement.org/en/life/restoring-savannas-and-tropical-herbaceous-ecosystems/.

The articles in the Encyclopedia of the Environment are made available under the terms of the Creative Commons BY-NC-SA license, which authorizes reproduction subject to: citing the source, not making commercial use of them, sharing identical initial conditions, reproducing at each reuse or distribution the mention of this Creative Commons BY-NC-SA license.