Environmental taxation

PDF

Environmental taxation, regardless of the regular revenue it provides to public authorities, influences taxpayers’ behaviour to make them aware of the negative effects of their activities on, in particular, biodiversity, natural resources and health. It is organised around binding, dissuasive and incentive measures, the wide variety of which highlights the importance of the tax system in protecting the environment.

1. What are the foundations of environmental taxation?

1.1. The internalisation of externalities

The theory of the internalisation of externalities, according to Pigou [1], is based on the observation that the price of goods, which is fixed by market forces, does not reflect their total production costs when environmental costs are not taken into account. It consists in integrating the costs of prevention and pollution into the production costs of a company. The external effects of an activity on the environment are then affected by a monetary valuation that will have repercussions on the company’s balance sheet.

The internalisation of external effects cannot be total. From a pragmatic point of view, it is difficult to have the polluter take charge of all the consequences of his activity on the environment, if only because it is impossible to accurately measure the social cost (victim identification is difficult, the environment’s absorption capacities are different). The objective is therefore to seek the optimal level of internalisation that results from the cost-benefit analysis of polluting activity on society. Taxation is the simplest and most effective instrument to try to reach this level and to ensure the best balance between the cost of pollution and the cost of prevention.

To explain this theory, N. Caruana [2] takes the example of the price of a car at a dealer, to point out that the “hidden costs” linked to its production (pollution during the manufacturing process, scarcity of certain raw materials partially reflected in the selling price, etc.) and its use (polluting emissions from combustion engines are not taken into account, pollution from factories producing the energy of electric cars, inconveniences related to noise and congestion, deterioration of public roads, induced public health problems, etc.) and its disappearance (pollution during the destruction or recycling process, recycling costs, final waste, etc.)”.

1.2. The polluter-pays principle

The polluter-pays principle includes a preventive component since it aims to charge economic actors for the cost of accident prevention measures. It also has a curative component consisting of integrating the expenses related to cleaning up and restoring a site after a disaster. In both cases, internalisation is only partial, since only the cost of reasonable measures is charged to the polluter.

Taxation applies this principle by integrating the cost of water pollution control, waste collection, disposal and greenhouse gas emissions into the atmosphere (see A carbon cycle disrupted by human activities). These various environmental impacts require specific financial instruments because of their specific problems. Hence the implementation of multiple tax measures: taxes, fees, pollution permits, subsidies and subsidies. Each tax instrument is able to respond to an environmental problem by obliging or encouraging economic actors to reduce their pollution and nuisances.

2. What are the different types of tax instruments?

Tax tools are in principle based on constraint. They are set out in norms and rules that prohibit or authorize behaviour. Thus, the taxpayer pays a tax, a tax, a fee established by law [4]. In principle, this restrictive tax system has a clear budgetary objective: the objective is to provide public funds in order to be able to finance expenditure covered by public entities [5]. It is not intended to guide the taxpayer’s behaviour. However, its proceeds may be used for environmental actions. This is the case, for example, of part of the proceeds of the general anti-pollutant tax from which ADEME (Agence de l’environnement et de maîtrise de l’énergie) benefits.

Environmental taxation is made up of “all the tax instruments instituted with the objective of contributing to the protection of the environment. (…) This objective can be achieved in three ways: by deterrence, by deterrence, by behaviour or by the use of a particular pollutant product; by encouraging action in favour of the environment; or by allocating the sums collected to the preservation of environments and resources. These three modalities can therefore take the form of taxes (TGAP) or higher rates of taxation, tax expenditures (exemption from property tax, accelerated depreciation, or taxes that are not intended to provide guidance, but whose proceeds make it possible to finance protective actions” [6]. This taxation can have a behavioural aim as long as it is intended “to guide the taxpayer’s choices by the threat of additional tax costs” [7]. The climate-energy contribution contributes to this approach by proportionally taxing carbon dioxide emissions from fossil fuels.

At the same time, this behavioural taxation is characterised by its incentive dimension. This is called a positive incentive measure because it leads the economic actor to act in favour of the environment. Thus, to promote energy savings, the 2015 Finance Act introduced a tax credit for households that carry out work to improve the energy performance of their main residence.

The tax measures developed for this purpose, whose wide variety ensures increasing yields [8], are essentially based on energy, transport, pollution and natural resources in order to take into account the main environmental issues (energy, climate change, biodiversity, pollution and the consumption of natural resources). Thus, in addition to taxes allocated to environmental expenditure, taxes and charges are combined with disincentives and incentives that are increasingly important in the tax system (pollution permits, subsidies, subsidies and incentive pricing). Among these multiple tax instruments, five categories can be identified, which will be described below:

- Taxation of fossil fuels

- Taxation of water pollution and use

- Permits to pollute

- Grants and subsidies

- Incentive pricing

2.1. Taxation of fossil fuels

Environmental taxes, which are mainly based on energy consumption linked to the use of fossil fuels, have evolved in recent years to include greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and thus put a price on carbon. In addition to the General Anti-Pollutant Tax (TGAP), which was created in the 1990s and includes several environmental taxes on air pollution, waste and polluting installations (installations classified for environmental protection), an energy tax has been developed to combat global warming and promote energy savings and energies with the lowest GHG emissions.

We can highlight the controversial introduction of the carbon tax. A first attempt at an institution was made in the initial finance law for 2010. However, the Constitutional Council [10], which was asked to verify the constitutionality of the law, censored the provisions relating to this tax by declaring them not in conformity with the Constitution. It considered them contrary to the principle of equality before the tax provided for in Article 13 of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, in view of the large number of exemptions provided for.

The effectiveness of this system should be put into perspective because of the total or partial exemptions it provides, which concern, in particular, installations covered by the Community emissions trading system (see below 2.3), as well as certain economic sectors considered fragile or subject to international competition (in particular road transport operators, public transport and taxis operators, inland waterway freight transport, air transport outside tourism aviation, agricultural operators, fisheries and maritime navigation outside pleasure craft). These sectoral exemptions from “domestic consumption tax (ICT) are the main subsidies that damage the environment. They illustrate one of the difficulties that governments face when they wish to reduce these subsidies, since some of them are intended for economic sectors that report difficulties in a context of international competition (agriculture, road freight), while another part targets sectors that are favourable to the environment (public transport)” [11].

2.2. Taxation of water pollution and use

- the domestic pollution charge, which is proportional to water consumption. It is calculated by taking into account the volume of water consumed by each inhabitant.

- The charge for non-domestic pollution which concerns any economic or industrial activity generating polluting discharges. It is proportional to the amount of pollution discharged into the aquatic environment (Figure 5).

Similarly, product royalties are included in the prices of polluting products at the time of their manufacture or use. This includes, for example, the levy for diffuse pollution on sales of plant protection products (former TGAP phytosanitary). This taxation takes into account the level of toxicity and dangerousness of the substances in the latter. Distributors of phytosanitary products in France and users (farmers or buyers) who source their products abroad are liable for this.

The name of these levies is misleading, because they are in reality taxes and not royalties, because they are not “the direct and individualizable counterpart of a service rendered” [12]. However, it should be noted that the pollution charge is an incentive, since it is proportional to the quantity of pollution released into the environment or to the damage resulting from it. This proportionality encourages the reduction of pollution.

2.3. Permits to pollute

The bonus-malus, one of the key measures of the Grenelle Environment Round Table, was created by the 2007 Amending Finance Act. Its incentive dimension tends to encourage the renewal of the vehicle fleet towards vehicles that emit less greenhouse gases (GHGs). Individuals and companies are encouraged to choose models that are less polluting and emit fewer grams of CO2 in order to receive a bonus.

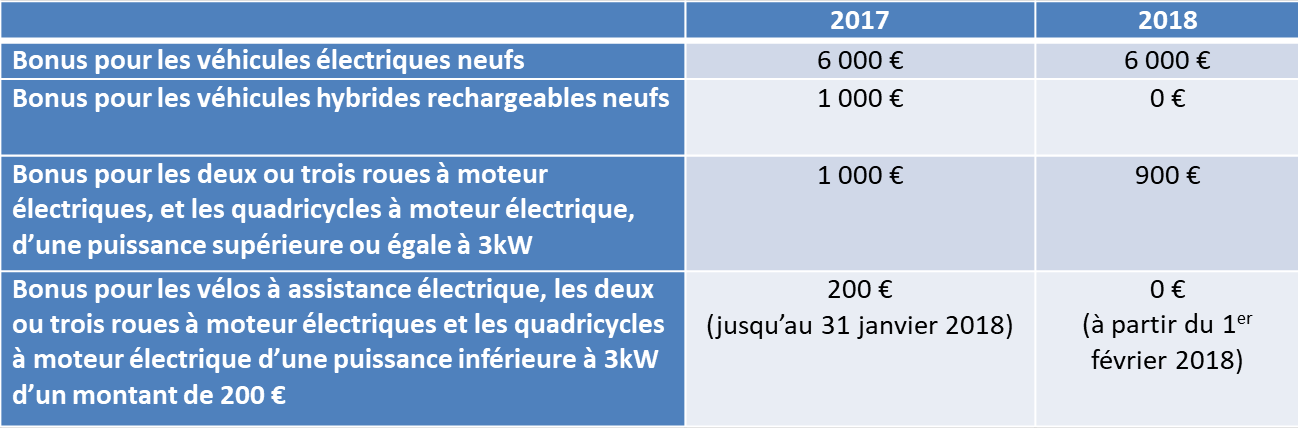

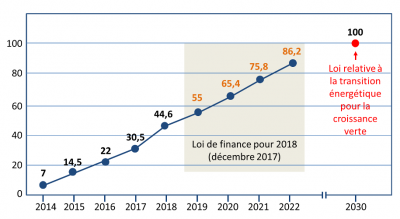

The bonus-malus system is based on a scale that has evolved since its creation in the direction of severity. The bonus is less accessible, since only cars emitting less than 60 grams of CO2 can benefit from a bonus of 1000 €. The bonus amounts to €6,000 in the case of electric vehicles that emit less than 20 grams of CO2, and up to €10,000 in the case of scrapping a diesel vehicle that is more than ten years old. The penalty has increased significantly, to €10,000 when CO2 emissions are greater than or equal to 191 grams. Two, three and four-wheelers and quadricycles also benefit from a bonus that depends on their power.

The 2018 finance law maintains the bonus-malus system while making it less attractive. In particular, it maintains the €6,000 bonus for the purchase of electric vehicles, but limits the total aid granted for the disposal of an old diesel or petrol vehicle to €8,500. The same can be said for the purchase of two, three or four-wheeled vehicles with electric motors, where the bonus is eliminated for low-powered vehicles (Table 1). The penalty scale is modified by the 2018 finance law in the sense of severity to subject vehicles emitting more than 120 grams of CO2 to a tax of 50 €, and to reach 10 500 € in the event of CO2 emissions greater than or equal to 191 grams.

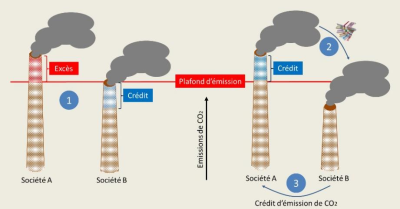

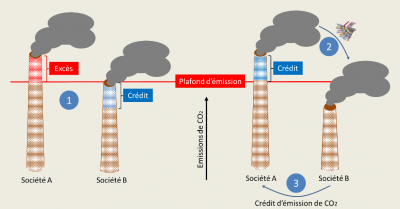

The emissions permit market is based on market forces to reduce the amount of GHGs in the atmosphere, which is responsible for climate change. An overall volume of GHG emissions not to be exceeded is determined at the state level. It will be distributed among the industries concerned. The market is created by the fact that pollution permits (quotas) from one polluter can be sold to another. This is possible when the manufacturer has polluted less than expected, due to new installations limiting pollution, and when, conversely, the competitor exceeds its CO2 emission quota (Figure 8).

2.4. Grants and subsidies

Apart from exemptions that appear to be “harmful subsidies” to the environment, such as those applicable to the domestic consumption tax [16], financial aid encourages economic actors to change their behaviour in order to reduce their polluting emissions. Farmers and industrialists thus benefit from financial support from the water agencies in carrying out work to improve their structures. Individuals have two mechanisms at their disposal set up by the State to improve the energy performance of their homes.

The eco-loan at zero interest rate (eco-PTZ) was instituted by the Finance Act for 2009. With a maximum amount of €30,000, it benefits homeowners who live in or rent their homes, without any conditions of resources since the 2017 Finance Act, in order to finance eco-renovation work – work that promotes energy saving and the reduction of GHG emissions. The work must be carried out by a certified EGR (Recognized Environmental Guarantor) company.

The Energy Transition Tax Credit (ECITC) [17], which can be combined with the previous loan, is granted to owners or tenants who make expenditures in favour of the environmental quality of their main residence. It allows 30% of the amount of expenditure linked to work to improve energy performance to be deducted from income tax, but does not exceed a multiannual overall ceiling of €8,000 for a single, widowed or divorced person, and €16,000 for a couple or partners linked by a civil solidarity pact, subject to joint taxation [18]. In addition, to benefit from it, conditions related to the company’s EGR certification are required for certain work. The Finance Act for 2018 provides for the introduction of a bonus to replace an old fuel oil boiler with a boiler using renewable energies (heat pump, wood boiler).

2.5. Incentive pricing

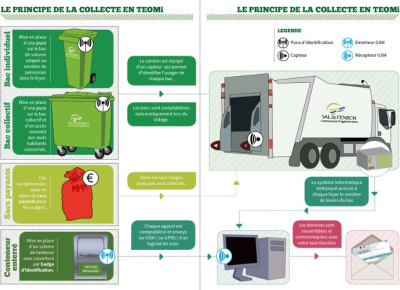

Special tax mechanisms try to make users aware of the consequences of their lifestyle on the environment by applying taxes to them depending on the pollution they generate. The incentive dimension is then predominant.

It applies in parallel with the principle of extended producer responsibility, whereby manufacturers, importers or distributors of products (medicines, electrical equipment, tyres, batteries, household products, textiles, etc.) are encouraged to prevent and limit the production of waste at source and to promote its recovery, by paying a contribution to an approved body to finance the collection and treatment of waste from these products.

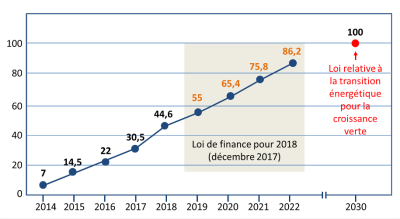

This system, which has been booming in France since 2010, will reach 5 million inhabitants in 2015. It is very effective in encouraging waste sorting and reduction: in the communities where it is applied, the quantities of packaging and paper sorted increase by one third and the quantities of unsorted waste are reduced by one third. The Energy Transition for Green Growth Act 2015 has a target of 15 million people covered by 2020 and 25 million by 2025[11].

The fight against air pollution (see How does the law protect air quality?) is based, in particular, on the application of parking taxes, the high rates of which can have a dissuasive effect on car use. The purpose of this behavioural taxation is to limit car traffic in city centres and to promote alternative modes of transport (public transport, cycling, walking, etc.) in order to reduce emissions that pollute the atmosphere. This policy is sometimes misunderstood and can anger taxpayers (Figure 11).

3. Messages to remember

- Environmental taxation, the main foundations of which are the theory of internalisation of externalities and the polluter-pays principle, has not only a financial but also an economic purpose. It is a behavioural tax that contributes to taxpayers’ awareness of the harmful impact of their activities on the environment.

- It is a monetary response to major environmental issues by developing tools that focus on energy, transport, pollution and natural resources.

- Beyond its binding nature, it includes dissuasive and incentive measures such as pollution permits, subsidies, subsidies and incentive pricing.

References and notes

Cover image. Montage of Jacques Joyard, on a royalty-free image. [Source: By why 137 from Trieste, Italy (2/2Uploaded by Sporti)[CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons ]

[1] Pigou A., 1920, The Economics of Welfare, Macmillan.

[2] Caruana N., 2015, La fiscalité environnementale. Between tax imperatives and environmental objectives, a conceptual approach to environmental taxation, L’Harmattan, p.32.

[3] The Environmental Charter was inserted into the preamble of the Constitution of 4 October 1958 by the Constitutional Act of 1 March 2005.

[4] Under section 34 of the 1958 Constitution.

[5] Caudal S., 2014, La fiscalité de l’environnement, LGDJ, p. 28.

[6] Ibid, p. 33.

[7] Collin P., Environmental Taxation and Constitution, New Constitutional Council Papers, No. 43, April 2014.

[8] In 2015, all so-called ecological taxes and duties had a return almost equal to that of income tax (62.1 and 69.3 billion euros respectively). It may be noted that, while ecological taxation increased overall by 12.1% between 2012 and 2015, it increased by 18.9% between 2007 and 2012, i.e. even more significantly (Information report on the application of tax measures, V. Rabault, Rapporteur General, Committee on Finance, the General Economy and Budgetary Control, National Assembly, 19 July 2016, www.assemblee-nationale.fr).

[9] The tax base is the basis of taxation. It concerns the environment: it can be a natural resource whose use will be taxed (water, energy source…), or a nuisance or product harmful to the environment (waste, pollution of a resource, fuel…). (Caudal S., La fiscalité de l’environnement, LGDJ, 2014, p.24-25).

[10] Decision of the Constitutional Council, 29 December 2009, Initial Finance Act for 2010.

[11] CGDD Report, Ministry of the Environment, January 2017, La fiscalité environnementale : un état des lieux www.agriculture.gouv.fr

[12] Caudal S., La fiscalité de l’environnement, prec. , p.25.

[13] Decree No. 2016-858 of 29 June 2016 on air quality certificates, www.legifrance.gouv.fr.

[14] Decree No. 2017-782 of 5 May 2017 strengthening sanctions for non-compliance with the use of air quality certificates and emergency measures in the event of an air pollution episode, www.legifrance.gouv.fr.

[15] Herald B., May 31, 2017, The right price for carbon: $50 to $100 per tonne in 2030, www.novethic.fr

[16] See above 2.1 Taxation of fossil fuels.

[17] It has replaced the sustainable development tax credit since its introduction by the 2015 finance law.

[18] http://bofip.impots.gouv.fr

The Encyclopedia of the Environment by the Association des Encyclopédies de l'Environnement et de l'Énergie (www.a3e.fr), contractually linked to the University of Grenoble Alpes and Grenoble INP, and sponsored by the French Academy of Sciences.

To cite this article: BALLANDRAS-ROZET Christelle (February 10, 2019), Environmental taxation, Encyclopedia of the Environment, Accessed July 27, 2024 [online ISSN 2555-0950] url : https://www.encyclopedie-environnement.org/en/society/environmental-taxation/.

The articles in the Encyclopedia of the Environment are made available under the terms of the Creative Commons BY-NC-SA license, which authorizes reproduction subject to: citing the source, not making commercial use of them, sharing identical initial conditions, reproducing at each reuse or distribution the mention of this Creative Commons BY-NC-SA license.