Check dams on torrents, why?

PDF

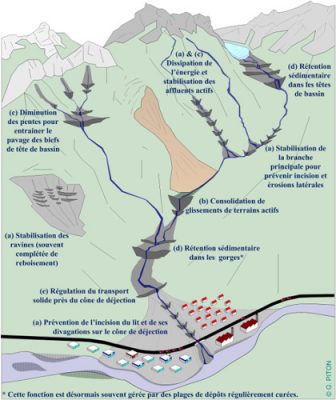

In the headwaters of the Alps, the Pyrenees and the Massif Central, mountain torrents are equipped with thousands of torrential check dams. What are they used for? They limit erosion and some of the risks associated with the torrential nature of these rivers. These structures have an important role in protecting mountain societies. They also have an impact on the environment through the stabilization of erosive processes. Their design requires an understanding of their effects on torrent activity and in particular on floods. This article recalls, through references to pioneer publications, how the current vision of the role played by check dams in torrents has emerged and changed through time. We shall see that a structure as simple as a check dam filled by pebbles can be built for very different purposes and have very specific effects and functions depending on its location and characteristics.

1. An old need for protection against floods and erosion

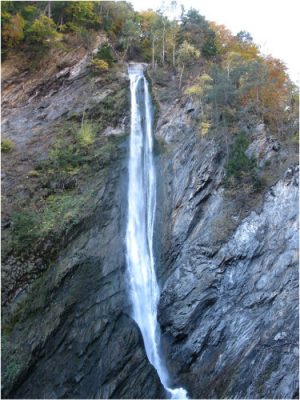

Hikers in the mountains near streams and torrents often notice dams filled with gravel and cobbles, especially in state-owned forests. It is surprising to note the presence of these structures made of cut stone, masonry or reinforced concrete so high on watercourses. Their purpose is not directly related to hydroelectricity or old mills: they are erosion control and torrential flood control structures.

Torrential floods cause considerable damage and sometimes casualties. Engineers have long been interested [1] in these phenomena, which originate in the geomorphology of mountains, i.e. the shapes of landscapes and their evolution over time, mainly during floods.

River training and channelization techniques developed on river courses quickly found their limits in the torrential context of Alpine development [1]. It was during Napoleon III’s Second Empire, established in 1852, that the reforestation of the mountains was launched in France. Such a policy, consisting in reforesting huge areas of grazed and eroded areas, could only be the result of a combination of several concomitant factors [2] :

- a centralized administration of an authoritarian Second Empire;

- projects for major infrastructure works and the securing of strategic transport networks (roads and railways);

- more than half a century of activity of a “forester” lobby [3];

- a hydrological crisis in the middle of the 19th century (major floods on most of the major French river systems, see Hydrometry: measuring the flows of a river, why and how? and associated focus).

This ambitious reforestation program was set out in the 1860 and 1864 laws. This was a first before similar decisions were taken by Switzerland in 1876, Italy in 1877, Austria in 1884 and Japan in 1897.

After the fall of the Second Empire in 1870, the Law on the Restoration and Conservation of Mountain Lands (RTM) was proclaimed in 1882. The new republican assembly, listening to the rural populations, reduced the ambitions of reforestation: the work effort would be concentrated where “restoration work [would] be made necessary by soil degradation, and the dangers born and present“. This means mainly torrent beds, gully systems, avalanche corridors and landslides. New projects would therefore be based more on civil engineering and less on extensive reforestation operations [4].

The period between 1882 and the beginning of the First World War was the “golden age of the RTM”. Generations of engineers working at that time had the means to correct more than a thousand torrents using techniques combining forestry engineering, bio-engineering for small structures [5] (bundles of branches called fascines & vegetated benches) and civil engineering for dikes, tunnels, sills and check dams [2]. These are the most visible and emblematic works in the field of torrential control and are the subject of this article.

Our mountain societies have inherited thousands of protective structures. The latter sometimes require maintenance operations, are sometimes abandoned or, by contrast, new structures using new techniques are implemented such as open check dams [6]. The decision to abandon, maintain or improve a torrent control system can only be understood by the populations concerned if they are able, in the first place, to understand the function of this system, i.e. its qualitative effects on floods and on the activity of the torrent. We will begin by recalling, through references to pioneer publications, how the vision of the role played by check dams emerged and changed through time. We will see that, depending on its location and characteristics, a structure as simple as a dam filled with pebbles, filtering or not, can be built for a wide variety of purposes and have specific effects and functions.

2. The pioneers

2.1. The “foresters”

During the 19th century, a strong forester lobby worked to curb uncontrolled deforestation and to initiate mountain regreening [3]. The regulatory role of the water regime is a recurrent argument of the different currents that animate it, but a second aspect eventually emerges: the erosion prevention [7].

Jean Antoine Fabre (1748-1834) published a pioneering book [8] (Figure 1). This early geomorphologist points out that a different treatment from that of rivers had to be implemented on torrents: stabilising the source of sediments by reforestation (see focus).

Alexandre Surell (1813-1887) took up and deepened the reflections of Fabre and other authors of the time to write his excellent “Study on the torrents of the Hautes Alpes”[9] (Figure 2). The first part of the book is a high-quality monograph on the origin of torrential activity. The second part is a partisan pamphlet against deforestation of the slopes and a harangue to the authoritarian reforestation of the mountains.

Fabre, like Surell, considered the use of check dams insufficient in itself, but interesting in order to stabilize banks and stream beds to facilitate reforestation (see focus, section 1).

2.2. The barrages makers

Scipio Gras (1806-1873) [10], Philippe Breton (1811-1892) [11] and Michel Costa de Bastelica (1817-1891) [12] later focused on the design and functions of check dams. These engineers tried to focus the design of protection structures on flood processes, stressing the need to adapt the protection system to the peculiarities of the catchment.

They highlight that, unlike river systems, the origin of hazards in the case of torrents is related to solid transport excess rather than liquid discharge excess. The resulting hazards (debris flows, debris floods, mudflows, floods, sedimentary deposits) are the result of a sediment supply exceeding the transport capacity of the flow, which is strongly correlated to the slope of the reaches. Gras and Breton recommend that channels on alluvial fans should not simply be embanked; this would simply mean sending the same problem of sediment excess further downstream. The downstream river system (river or agricultural drainage ditches), with insufficient slope to transport this solid load, would then tend to aggradated, i.e., increase their bed level, with or without dikes. The increase in the bed level would even be all the more rapid – and therefore more dangerous to manage – if the bed width were constrained by dikes leaving less space to the volume to contain.

3. Waters and Forests

The manuals [14] [15] for restoring the Demontzey and Thiéry mountains synthesizing the first techniques will be refined later by Kuss [16] [17] and Mougin [18] in the particular cases of torrents prone to glacial lake outburst floods (Figure 4 & Figure 5), consolidation work on large landslides and rock avalanches (Figure 6). They also use drainage or diversion systems and bypass such large scale instabilities (Figure 7).

- Bed stabilization

- Hillslope consolidation

- Reduction of bed slopes (read focus, section 3)

- Sediment retention

- Regulation of solid transport

The number of new projects decreased between the two world wars, and the large number of structures yet built had to be maintained. The post-war period saw the advent of two technologies that would revolutionize torrent control: reinforced concrete and earthmoving machinery [4]

The use of reinforced concrete made it possible from 1955 onwards to design and build cantilever check dams. These are less expensive than masonry gravity check dams for large dams [2]. Reinforced concrete can also be used to build new structures such as filter dams and open check dams that close off debris retention basins. The conceptualization and first tests of filtering dams, carried out in the 1950s and 1960s, are considered a world first [2] The mainstreaming of these structures in France took place a little later, after the transfer of the former responsibilities of Water and Forests to the new National Forest Office in 1966.

4. A huge park of structures to be managed

In 1964, the former Water and Forestry Administration had 92,873 check dams and weirs, 10 diversion tunnels, 736 km of drainage networks built in the 26 French departments in accordance with RTM laws [21]. In 1966, the management of these structures was transferred to the ONF: Office National des Forêts (with a partial and temporary transfer to the DDA: Directions Départementales de l’Agriculture), and in 1971 in some departments to the care of a specific Service de Restauration des Terrains de Montagne at the ONF [22] (ONF-RTM).

Only a part of these works is regularly monitored on behalf of the State in the 11 mountain departments of the Pyrenees and the Alps, which still include an ONF-RTM service [21]. Rural depopulation, decreased grazing, climate change since the end of the Little Ice Age and spontaneous or artificial reforestation have reduced erosion activity in many watersheds. Others that are still very active are still regularly the subject of maintenance and investment work to protect populations as well as the various downstream assets, road and rail networks.

The management of check dams is now being considered in terms of the effectiveness of the structures (adequacy between objective and capacity achieved) and their efficiency (adequacy between overall effectiveness and cost). These analyses aim, in parallel with other criteria, to optimise investment and maintenance funds; but their implementation is hampered by the complexity of torrent morphodynamics, the difficulty of characterising the capacity of a structure (its quantified effect on flooding), as well as the cumulative effects with risks of ruptures and potential cascading effects [23].

The management of the immense French fleet of torrent control works therefore requires a better understanding of the potential effects of check dams by all stakeholders (ONF-RTM, State, local elected officials, populations, risk managers). Although the quantification of these effects and their aggregation is a complex subject requiring professional expertise, we advocate that everyone can understand their general principles. This paper provides a first overview.

References and notes

Cover image.

[1] Vischer, D. L. 2003. History of flood protection in Switzerland, From the origins to the 19th century. OFEG, Water Series. http://assets.wwf.ch/downloads/histoire_protection_contre_crues__suisse.pdf

[2] Piton, G. 2016. Sediment transport control by check dams and open check dams in Alpine torrents. Grenoble Alpes University, IRSTEA – Centre de Grenoble. Chapter 1. https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-01420209

[3] Kalaora, B., and A. Savoye. 1986. The pacified forest. Forestry and sociology in the 19th century. L’Harmattan, France.

[4] Brugnot, G. 2002. Development of forest policy and the emergence of mountain land restoration. Pages 23-30 in Annales des ponts et chaussées. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0152-9668(02)80031-6

[5] Genialp. 2012. Plant engineering in mountain rivers – knowledge and feedback on the use of plant species and techniques: vegetation of banks and wooden structures. Page (L. Bonin, A. Evette, P.-A. Frossard, P. Prunier, D. Roman, and N. Valé, Eds.). Europeen Union and Swiss Confederation. http://cemadoc.irstea.fr/cemoa/PUB00038614

[6] Structure dedicated to the trapping of solid load (sediment and wood), generally consisting of a sedimentation basin, closed by a civil engineering structure, pierced by openings, called “filtering barrier”, see Piton, 2016, ibid. chapters 2 & 3. these areas are regularly cleaned by earthmoving machinery.

[7] Durand, A. 2003. Role of the forest in floods. White Coal: 129-134.

[8] Fabre, J.-A. 1797. Essay on the theory of torrents and rivers. 342 p. Bidault Libraire, Paris. https://books.google.fr/books?id=fxkOAAAAAAQAAJ

[9] Surell, A. 1841. Study on the torrents of the Hautes Alpes. 280 p. . Library of the Imperial Corps of Civil Engineering and Mining, Paris. http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k96017215

[10] Gras, S. 1850. Presentation of a system for defending torrential rivers in the Alps and application to the Romanche torrent in the department of Isère. 112 p. Charles Vellot, Grenoble. http://www.e-rara.ch/doi/10.3931/e-rara-16678

[11] Breton, P. 1867. Brief on gravel dams in stream gorges. Paris. http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k6338240f

[12] Costa de Bastelica, M.. 1874. The torrents : their laws, their causes, their effects, the means to repress and use them, their universal geological action. Librairie Polytechnique, Paris. http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k28386p

[13] Gras, S. 1857. Studies on Alpine torrents. 108 p. F. Savy, Paris. http://www.e-rara.ch/doi/10.3931/e-rara-16676

[14] Demontzey, P. 1882. A Practical Treatise on Mountain Reforestation and Turfgrassing. 528 pp. Ministries of Agriculture and Trade and Public Works, Paris http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k6130912k

[15] Bernard, C. 1927. Mountain Restoration Course. 788 pp. École normale des eaux et forêts.

[16] Kuss, C. 1900a. Restoration and conservation of mountain land. The Glacial Torrents. 88 p. Imprimerie Nationale. http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k6357324x

[17] Kuss, C. 1900b. Restoration and conservation of mountain land. Landslides, landslides and dams. 61 p. Imprimerie Nationale. http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k64593256

[18] Mougin, P. 1900. Restoration and conservation of mountain land – consolidation of banks by diverting a torrent (Saint Julien torrent). 39 p. Imprimerie Nationale http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k6462342t

[19] Charles Kuss’ photo album, three volumes, date unknown (late 19th century). IRSTEA Archives, Centre de Grenoble

[20] Water and Forests (1911a). “Restoration and conservation of mountain lands. Part two, Summary description of the restoration perimeters, Alps Region.” Under the direction of the Ministry of Agriculture – Directorate General of Water and Forestry. 215p. National Printing House.

[21] Carladous, S., G. Piton, J. Tacnet, F. Philippe, R. Nepote-Vesino, Y. Quefféléan, and O. Marco. 2016b. Protection against natural hazards in French mountains: historical analysis of actions and decision contexts in public forests. Pages 34-42 13th INTERPRAEVENT Conf. Process http://interpraevent2016.ch/assets/editor/files/IP16_CP_digital_CP.pdf

[22] ONF-RTM services are specialized services that exist only in certain areas of the territory. Today, the NFB is represented in the territories by territorial agencies whose scope of action is larger than the department (51 agencies). Then there are 320 territorial units for representation throughout the country.

[23] Carladous, S. 2017. Integrated decision support approach based on the propagation of information imperfection in the expertise process – application to the effectiveness of torrential protection measures. Doctoral thesis. AgroParisTech, Ecole des Mines de Saint-Étienne.

The Encyclopedia of the Environment by the Association des Encyclopédies de l'Environnement et de l'Énergie (www.a3e.fr), contractually linked to the University of Grenoble Alpes and Grenoble INP, and sponsored by the French Academy of Sciences.

To cite this article: PITON Guillaume (May 6, 2022), Check dams on torrents, why?, Encyclopedia of the Environment, Accessed April 20, 2024 [online ISSN 2555-0950] url : https://www.encyclopedie-environnement.org/en/water/dams-on-torrents-why/.

The articles in the Encyclopedia of the Environment are made available under the terms of the Creative Commons BY-NC-SA license, which authorizes reproduction subject to: citing the source, not making commercial use of them, sharing identical initial conditions, reproducing at each reuse or distribution the mention of this Creative Commons BY-NC-SA license.