Climate change and globalization, drivers of insect invasions

PDF

Global warming and globalization of trade have a decisive impact on the geographical distribution of insects. There is an exponential increase in the establishment of non-indigenous insects worldwide, along with the development of commercial networks. At the same time, global warming is promoting the expansion of many insect species northward and to higher altitudes. These two factors combined explain the multiple insect invasions observed in recent years.

- 1. An explosion of the establishment of non-native insects in Europe

- 2. Non-native species are spreading faster and faster across Europe

- 3. Global warming is changing the range of insects

- 4. Annual increase in average temperature, a relevant variable?

- 5. Expansion to the North and contraction to the South?

- 6. Globalization and global warming act in a combined way

- 7. Global warming alone is responsible for the expansion of insects?

- 8. Messages to remember

1. An explosion of the establishment of non-native insects in Europe

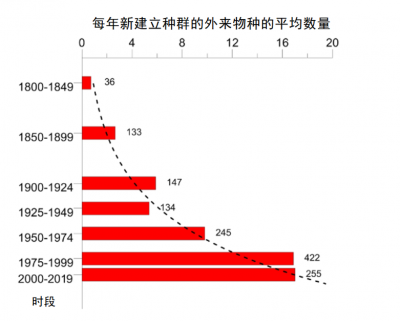

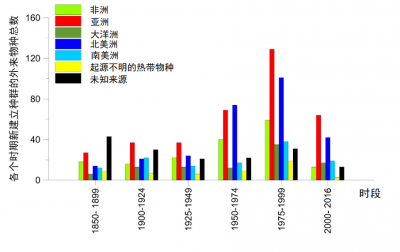

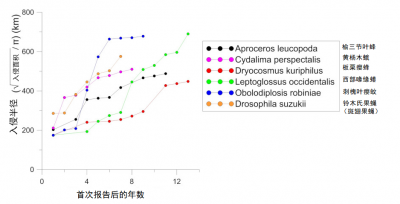

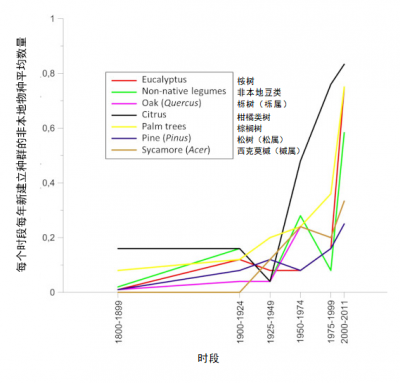

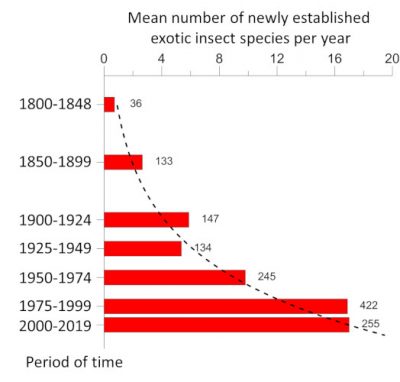

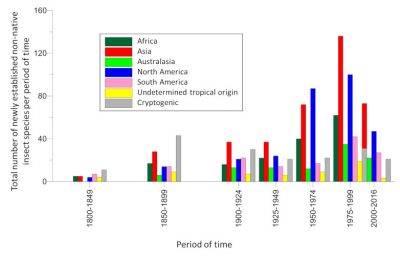

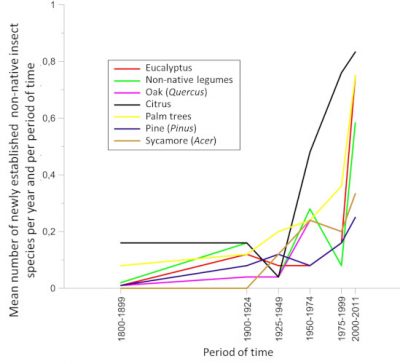

While the destruction of natural habitats is the primary cause of the current decline in biodiversity, invasions of non-native species are in second place. The rate of establishment of non-native insect species, i.e. introduced on a continent other than that of origin, has increased exponentially since the beginning of the 20th century. Thus, in Europe, the number of newly established species increased from 9.7 per year during the period 1950-1974 to 17.0 during the period 1990-2016 [1] (Figure 1). By the end of 2016, 1418 non-native insect species had been identified as introduced and established in Europe [2], making it the 2nd largest group of non-native species after plants [3] (see When invasive plants also wander in the fields). Similar values are observed on other continents [4].

Nowadays, species qualified as “emergent” (because they have never previously been introduced in a continent other than the one of origin [6]) have become predominant. This is the case, for example, of the Asian hornet detected in France in 2004.

2. Non-native species are spreading faster and faster across Europe

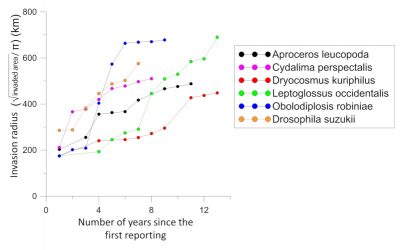

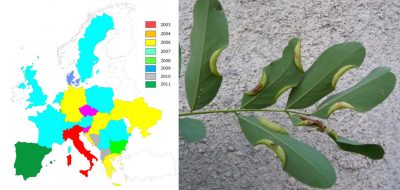

There is an acceleration in the rate of expansion of non-native insects. Non-native species that have become established in Europe over the past two decades have a faster average rate of expansion than those that arrived just after World War II [1]. Many of them colonized almost the entire continent in less than fifteen years, while most species established in the first half of the 20th century took several decades to achieve this. Several examples indicate that this expansion rate is independent of the origin of the introduced insect (Figures 4 and 5).

Insects of Asian origin have spread even more rapidly, colonizing most of Europe in less than 10 years:

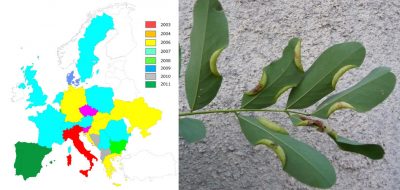

- The box tree moth, Cydalima perspectalis (Figure 4), was first detected in 2006 in Germany [8];

- The spotted wing Drosophila, Drosophila suzukii (Figure 4), detected in 2008 in Italy [9].But it also true for a moth of South American origin, the tomato leafminer, Tuta absoluta (Figure 4), first observed in 2006 in Spain [10].

- 4 times higher than that of species established just after the Second World War (1950-1969),

- 3 times higher than that of the species detected during the period 1970-1989 [1].

This recent acceleration in the expansion of non-native insects (Figure 5) could be linked to the political and economic changes in Europe (fall of the Berlin Wall and enlargement of the European Union), with in particular the abolition of intra-Community customs controls [1].

- Box tree moth (Cydalima perspectalis) and western conifer seed bug (Leptoglossus occidentalis) increased over a year by more than 150 km radius (Figures 4 and 5) while adult flight capacity was estimated at a few tens of kilometres [8].

- A very small midge (adult size: 5 mm) of North American origin, the black locust gall midge (Obolodiplosis robiniae) has progressed in 2 years by more than 450 km (Figures 5 and 6) [1].

3. Global warming is changing the range of insects

With an increase in global average temperature of 0.61°C since the beginning of the 20th century and a future warming estimated at between 2.6 and 4.8°C for 2100 according to the models of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC [12]), we can expect a significant impact of climate change on most insect species. This foreseeable impact is linked to the very biology of insects.

Insects are “cold” blooded animals that do not produce heat. They are called “ectotherms” unlike “endothermic” mammals, which are able to produce heat through their metabolic activity and keep their body temperature more or less constant. The body temperature of insects and the associated physiological processes will therefore depend directly on changes in ambient temperature. These variations will, among other things, govern their periods and rhythms of activity, the duration of their different stages of larval development and the number of annual generations, their flight possibilities, etc…. For a large number of species, specific temperature thresholds delimit barriers limiting their geographical distribution:

- Thus, the -16°C isotherm limits the chances of winter survival of the North American southern pine beetle, a major pest of conifers, Dendroctonus frontalis [13] (Figure 8), such as those of larvae of pine processionary moth (see Focus The pine processionary, a model…).

- But the +40° isotherm also limits the summer survival of the eggs of this same processionary moth [14].

- In Europe, 63% of non-migratory butterflies have seen their range increasing northward over distances of 35 to 240 km over the past century, along with the average isothermal movement of 120 km to the pole due to a warming of about 0.8°C [15].

- In western North America, the 92-km average northward expansion of the Euphydryas editha butterfly has also been linked to a 105-km northern displacement of isotherms during the same period [16].

- Similar phenomena of expansion northward and at higher altitudes of beetles, dragonflies and grasshoppers have been observed over the past 30 years [17].

However, a simple comparison of the past and current distribution of species with the movement of isotherms during the same period is not sufficient to prove the implication of climate change. To demonstrate that this cannot result from a simple correlation, it is essential to identify a causal link between a change in the range and a change in the climatic factor considered.

- Until the early 2000s, winter survival of the southern pine beetle (Dendroctonus frontalis- Figure 8) was only possible in the southeastern United States, due to its estimated lethal winter temperature of -16°C. This area was then the northern limit of the insect’s range. Latitudinal movement northward from the -16°C isotherm has allowed the insect to colonize areas at much more northerly latitudes in the northeastern United States [18].

- Winter survival of eggs of several species of geometric butterflies is also favoured in areas of northern Scandinavia previously unsuitable for their establishment (Figure 9).

- Cause-effect relationships have been experimentally established regarding the role of winter warming in the expansion of the pine processionary (see Focus The pine processionary, a model…) [19].

4. Annual increase in average temperature, a relevant variable?

Global warming is most often assessed from the increase in the average annual air temperature at sea level. However, insect populations are not confronted with an average temperature, but with a daily variation in the weather conditions under which they develop. Taking into account only the increase in annual temperature may mask the differential effects of seasonal warming.

Thus, an increase in temperature in winter, spring, summer, or fall will not have the same biological impact as a result of allowing populations to expand or not. While the increase in winter temperatures allows some species to survive in previously unfavourable areas, an increase in spring and/or summer temperatures will tend to accelerate the development of immature stages, allowing an increase in the number of annual generations in some species, and encourage movement.

- This is particularly the case for migratory butterfly species such as the noctuid Autographa gamma, whose incursions into Britain from overwintering sites in North Africa are facilitated by rising temperatures [20].

- In the Italian Alps, the 2003 summer heat wave also allowed the pine processionary moth to extend its distribution because nights when the temperature exceeded the threshold required for females to fly (14°C) were then 5 times more frequent than normal, allowing a greater proportion of moth to disperse over long distances [21].

5. Expansion to the North and contraction to the South?

Few data exist on the possible contraction of the distribution area to its southern limit with increasing temperatures. In most European butterflies, the southern limit of northward moving species appears to have remained stable, and only a few, such as the lycaenid butterfly Heodes tytirus, show a decline in populations south of the area [15]. For two species of moths (Lymantria dispar and L. monacha), simulations based on the foreseeable increase in temperatures in the future suggest a retraction of the southern limit from 100 to 900 km due to the negative effects of excessively high temperatures on larval hatching from eggs in winter diapause [22], a phenomenon that corresponds to a temporary pause in development in response to the occurrence of adverse climatic conditions.

More generally, for insects developing during spring and summer, changes in range could be roughly determined by a combination of development rate (fast or slow) and winter diapause process [23]:

- rapidly developing species, without diapause, will tend to increase the number of generations per year and increase their range (in the case of aphid species);

- fast-growing species, but with temperature-affected diapause, will tend to have their area shrink (case of European peacock butterfly, Inachis io, or small emperor moth, Saturnia pavonia);

- slow-growing species with temperature-affected diapause will tend to decline and have their area reduced (case of oak eggar, Lasiocampa quercus).

6. Globalization and global warming act in a combined way

7. Global warming alone is responsible for the expansion of insects?

Most studies to date have focused on the effects of rising temperatures. But climate change incorporates multiple other factors, such as humidity, rainfall intensity and frequency, radiation, or greenhouse gas levels, which can act directly or in synergy with rising temperatures. For example, the establishment in our regions of the asian tiger mosquito, Aedes albopictus, is conditioned by temperature but also by the length of the day compared to the night (photoperiod), humidity and rainfall [28]. But the other studies, most often conducted under laboratory conditions, so far give only often contradictory indications as to the possible responses of insects to fluctuations in these variables, for example on the effect of CO2 [29]. The development of large-scale field experiments appears essential.

Research on the relationship between climate change and insect expansion has often focused on the specific responses of insects with high economic or health impacts, rarely taking into account their associated organisms. However, climate change simultaneously affects the entire ecosystem, including host (plants), competing insects and natural enemies. The responses of each of these components may differ for the same temperature increase and the interactions may be significantly altered in one direction or another. For example, studies suggest that the effectiveness of some predators, such as ladybeetles, may increase in a warmer environment, and the expansion of aphid-prey may be reduced [30]. On the other hand, the pine processionary progresses faster northwards than its natural enemies [31]. The development of integrated studies, considering all ecosystem components simultaneously, is a necessity for future research.

8. Messages to remember

- The intensification and diversification of world trade, particularly in ornamental plants, is leading to an increase in the establishment of non-native insects in Europe.

- After their establishment, these insects tend to spread across Europe faster than in the last century.

- Warming, particularly in winter temperatures, removes climatic barriers limiting the range of a number of native or non-native species, and allows them to expand into areas previously unfavourable to their survival during the winter.

- Warming facilitates the establishment and spread of non-native species of subtropical and tropical origin.

Notes and references

Cover image. Massive attack by the pine processionary at its altitudinal expansion front in the Italian Alps. Oulx, Piedmont; winter 2015-2016. [Source: Photo Roques © INRA]

[1] Roques A., Auger-Rozenberg M.-A., Blackburn T.M., Garnas J.R., Pyšek P. et al. (2016) Temporal and interspecific variation in rates of spread for insect species invading Europe during the last 200 years. Biological Invasions 18, 907-920.

[2] Source: DAISIE European project database (“Delivering Alien Invasive Species Inventories in Europe”; http://www.europe-aliens.org) recently updated in the EASIN database (“European Alien Species Information Network“; http://easin.jrc.ec.europa),

[3] DAISIE (2009) Handbook of alien species in Europe. Berlin: Springer Science + Business Media B.V.

[4] Seebens H., Blackburn T.M., Dyer E.E., Genovesi P., Hulme P.E. et al. (2017) No saturation in the accumulation of alien species worldwide. Nature Communications. DOI: 10.1038/ncomms14435.

[5] Roques A., Rasplus J.Y., Rabistch W., Lopez-Vaamonde C., Kenis M et al. (2010). Alien Terrestrial Arthropods of Europe. BioRisk 4 (1 and 2), 1-1024.

[6] Seebens A., Blackburn T.M., Dyer E.E., Genovesi P., Hulme P.E. et al. (2018). The global rise in emerging alien species results from increased accessibility of new source pools. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. doi/10.1073/pnas.1719429115.

[7] Lesieur V., Lombaert E., Guillemaud T., Courtial B., Strong W. et al. (2018) The rapid spread of Leptoglossus occidentalis in Europe: a bridgehead Invasion. Journal of Pest Science. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10340-018-0993-x

[8] Bras A. Invasion fulgurante de la pyrale du buis en Europe: Caractérisation de la diversité génétique de Cydalima perspectalis (Walker, 1859) et approche phylogéographique https://belinra.inra.fr/doc_num.php?explnum_id=1021 (in french)

[9] Cini A., Ioriatti C., Anfora G. (2012). A review of the invasion of Drosophila suzukii in Europe and a draft research agenda for integrated pest management. Bulletin of Insectology 65(1) 149-160.

[10] Desneux N., Luna M.G., Guillemaud T. and Urbaneja A. (2011) The invasive South American tomato pinworm, Tuta absoluta, continues to spread in Afro-Eurasia and beyond the new threat to tomato world production. Journal of Pest Science 84, 403 – 408.

[11] Javal M., Roques A., Haran J., Herard F., Keena M., Roux G. (2017) Complex invasion history of the Asian long-horned beetle: fifteen years after first detection in Europe. Journal of Pest Science DOI 10.1007/s10340-017-0917-1.

[12] http://ar5-syr.ipcc.ch/

[13] Ungererer M.J., Ayres M.P., Lombardero M.J. (1999). Climate and the northern distribution limits of Dendroctonus frontalis Zimmermann (Coleoptera: Scolytidae). Journal of Biogeography 26, 1133-45.

[14] Faucet C., Rousselet J., Pineau P.; Miard F., Roques A. (2013). Are heat waves susceptible to mitigate the expansion of a species progressing with global warming? Ecology and Evolution 3(9), 2947-57.

[15] Parmesan C, Ryrholm N, Stefanescu C et al (1999). Poleward shifts in geographical ranges of butterfly species associated with regional warming. Nature 399, 579-83.

[16] Parmesan C (1996). Climate change and species’ range. Nature 382, 765-766.

[17] Hickling R., Roy D.B., Hill J.K., Fox R., Thomas C.D. (2006). The distributions of a wide range of taxonomic groups are expanding polewards. Global Change Biology 12, 450- 455.

[18] Trân J.K., Ylioja T., Billings R.F., Régnière J., Ayres M.P. (2007). Impact of minimum winter temperatures on the population dynamics of Dendroctonus frontalis. Ecological Applications 17, 882-899.

[19] Jepsen J.U., Hagen S.B., Ims R.A., Yoccoz N.G. (2008). Climate change and outbreaks of the geometrids Operophtera brumata and Epirrita autumnata in subarctic birch forest: evidence of a recent outbreak range expansion. Journal of Animal Ecology 77, 257-264.

[20] Chapman J.W., Reynolds D.R., Smith A.D., Riley J.R., Pedgley D.E., Woiwod I.P. (2008). Wind selection and drift compensation optimize migratory pathways in a high-flying moth. Current Biology 18, 514-518.

[21] Battisti A. Stastny M., Buffo E., Larsson S. (2006). A rapid altitudinal range expansion in the pine processionary moth produced by the 2003 climatic anomaly. Global Change Biology 12, 66- 671.

[22] Vanhanen H., Veteli T.O., Pailvinen S., Kellomaki S., Niemala P. (2007). Climate change and range shifts in two insect defoliators: Gypsy moth and nun moth – A model study. Silva Fennica 41, 621-38 ;

[23] Bale J.S., Masters G.J., Hodkinson I.D. et al. (2002). Herbivory in global climate change research: Direct effects of rising temperature on insect herbivores. Global Change Biology 8, 1-16.

[24] Eschen R., Roques A., Santini, A. (2015). Taxonomic dissimilarity in patterns of interception and establishment of alien arthropods, nematodes and pathogens affecting woody plants in Europe. Diversity and Distributions 21 (1), 36-45.

[25] Walther G R., Roques A., Hulme P.E., Sykes M.T., Pyšek P., et al. (2009). Alien species in a warmer world: risks and opportunities. Trends in Ecology and Evolution 24, 686-692.

[26] Roques A. (2010). Alien forest insects in a warmer world and a globalized economy: Impacts of changes in trade, tourism and climate on forest biosecurity. New Zealand Journal of Forestry 40, 77-94.

[27] Ott J., ed (2008). Monitoring climate change with dragonflies. Series Faunistica 81. Pensoft, Sofia. Cannon R.J.C. (1998). The implications of predicted climate change in the UK, with emphasis on non-indigenous species. Global Change Biology 4, 785- 796.

[28] Eritja R., Escosa R., Lucientes J. et al. (2005). Worldwide invasion of vector mosquitoes: Present European distribution and challenges for Spain. Biological Invasions 7, 87-97.

[29] Newman J.A. (2005). Climate change and the fate of cereal aphids in Southern Britain. Global Change Biology 11, 940-944.

[30] R.J.C. Cannon (1998). The implications of predicted climate change in the UK, with emphasis on non-indigenous species. Global Change Biology 4, 785-796.

[31] Auger-Rozenberg M.A., Barbaro L., Battisti A., Blache S.,. Charbonnier Y., et al. (2015). Ecological responses of parasitoids, predators and associated insect communities to the climate-driven expansion of pine processionary moth. pp. 311- 358 In Roques A. (Ed.) Processionary Moths and Climate Change: An Update. Springer/ Quae

The Encyclopedia of the Environment by the Association des Encyclopédies de l'Environnement et de l'Énergie (www.a3e.fr), contractually linked to the University of Grenoble Alpes and Grenoble INP, and sponsored by the French Academy of Sciences.

To cite this article: ROQUES Alain, AUGER-ROZENBERG Marie-Anne (August 16, 2019), Climate change and globalization, drivers of insect invasions, Encyclopedia of the Environment, Accessed July 27, 2024 [online ISSN 2555-0950] url : https://www.encyclopedie-environnement.org/en/life/climate-change-globalization-drivers-of-insect-invasions/.

The articles in the Encyclopedia of the Environment are made available under the terms of the Creative Commons BY-NC-SA license, which authorizes reproduction subject to: citing the source, not making commercial use of them, sharing identical initial conditions, reproducing at each reuse or distribution the mention of this Creative Commons BY-NC-SA license.