Economic theories in the face of the realities of environmental crises

PDF

In the Anthropocene era [1], it is no longer possible to leave the question of the relationship between economic activity and the environment, both in terms of the exploitation of natural resources and the degradation of natural environments, outside the scope of economic analysis. What are the instruments proposed by economic theory to manage them? Since the 1960s, environmental issues have continued to gain ground in the field of societal concerns. As well as the day-to-day degradation of biodiversity, air quality, greenhouse gas concentration or the availability of drinking water, a series of major disasters have alarmed public opinion and governments. Responses to these environmental impacts have resulted in public policies that seek to make the further improvement of material well-being compatible with the preservation of a certain quality of the environment. Often helpless in the face of population growth, governments have only been able to focus on the consequences of economic activity. As the initial use of regulations frequently resulted either in non-compliance with the standards imposed or in the excessive cost of controls, many governments turned, from the 1970s onwards, to other instruments advocated by economic theory. With several decades of hindsight, can we consider that these instruments have kept all their promises?

With the Second Industrial Revolution at the end of the 19th century, the globalization of economies, the unprecedented demographic and economic growth of the 20th century, it is becoming difficult to leave the issue of economic-environmental relations outside the scope of economic analysis. These are indeed increasingly intense, both in terms of the exploitation of natural resources and the degradation of natural environments, to the point that some consider that the continued growth is now endangering the planet. Does economic theory propose the appropriate instruments to deal with current and future environmental crises?

- 1. The price of natural resources

- 2. The cost of discharges and pollution

- 3. The Pigouvian tax

- 4. Markets for pollution rights or emission allowances

- 5. The reality check: progressive degradation and environmental disasters

- 6. The exploitation of natural resources

- 7. Rejection taxes and contracts for environmental access rights

- 8. Messages to remember

1. The price of natural resources

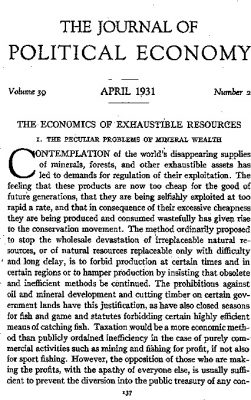

Resources are given by nature but, depending on the jurisdictions in force, they are appropriable. And in response to the American “conservationists” who argue that the price system does not allow for rational management of natural resources, Hotelling makes it possible to define, for the owner of a stock of goods that decreases as it is exploited, a rule to maximize the discounted value of its profits over a finite time horizon [5]. This rule can be formulated as follows (Figure 2):

- the owner of a deposit has two options at any time: either extract one more unit today, sell it and place its gain, or leave its deposit fallow, wait a while, and later sell the extracted unit on the market;

- the optimal exploitation rate of the resource is determined by equalising the market price and the marginal cost of production, to which is added a scarcity rent expressing the finiteness of the stock, thus the unavailability of the resource in the future; on this basis, it is in the operator’s interest to extract as long as its marginal cost is not higher than its marginal revenue (quantity x selling price);

- the price of the natural resource, and therefore the rent attached to it, must increase at a rate equal to the interest rate (or discount rate), which makes the conservation of the resource in situ equivalent to its extraction and the investment of the proceeds of its sale remunerated by interest.

According to this rule, the total volume of a resource, given by nature, constitutes for the owner a rent that justifies an increase in the price beyond marginal costs. This scarcity rent, unlike David Ricardo’s differential rent, therefore distinguishes the exploited natural resource, renewable or not, from other goods or services, but in so doing, it is treated as capital and presupposes its appropriation. In its absence (high seas fishing, for example), companies that are not interested in the optimal management of an open resource, i.e. one that cannot be appropriated, will seek to exploit it as quickly as possible, and therefore perhaps to exhaust it. The answer in terms of privatization of appropriable natural resources, put forward by some economists, is not always applicable, especially when it comes to global commons such as biodiversity [6].

Beyond the producer’s microeconomic logic analysed by Hotelling, the question of the exploitation of natural resources will be transposed to the global, or macroeconomic, scale after the publication of the Meadows report on “The Limits to Growth” in 1972 (Figure 3). For economists who have taken part in the debate, natural resources, renewable or not, can be treated like any other good. As such, they are reintroduced into growth models in a Cobb-Douglas-type production function: in these so-called KLEM production functions, natural resources, energy (E) and raw materials (M) are linked to other production factors, technical capital (K) and labour (L) by a substitution elasticity meaning that in case of a price increase, E and M can be replaced by K and L.

Consequently, the depletion of a natural resource is no longer to be feared since the increase in its price reduces its demand while making new deposits that have become accessible thanks to technological progress [7] profitable. Jeffrey Krautkraemer can thus state the paradox according to which non-renewable natural resources, which can be appropriated and thus benefit from price adjustments, are less threatened by depletion than renewable natural resources, which cannot be appropriated [8].

But other controversies have emerged around this issue, particularly between neoclassical “standard” economists and supporters of the “ecological economy”. For the former, if investment is sufficient, the destruction of natural capital can be compensated, from a social welfare perspective, by the accumulation of artificial capital: this is referred to as “weak sustainability“. For the latter, natural capital cannot be destroyed with impunity and a development model must be found that preserves critical stocks of natural capital: this is the concept of “strong sustainability“. The policy recommendations drawn from these two visions are obviously very different since they lead either to technological optimism or, on the contrary, to strict conservationism [9].

2. The cost of discharges and pollution

In parallel with the increased exploitation of natural resources, the economic activity of the industrial world has dumped and is dumping increasing volumes of solid, liquid or gaseous waste into the natural environment. The economic agents responsible for them (polluters) thus affect the value of goods or services, either collective (the air breathed by all) or appropriable (the water used in the manufacture of a product). Not regulated by public authorities, such practices distort the conditions of trade as long as they do not contribute to price formation. The theory of external effects proposes to remedy this deficiency according to well-defined principles and conditions [10].

An externality corresponds to the effect that an economic agent provides on the activities of other agents without monetary compensation, the effect being able to translate into an advantage (positive externality), or a damage and a nuisance (negative externality). Such effects, by distorting the costs on the basis of which each agent takes a decision, are a source of defective social allocation of activities, and therefore of economic inefficiency. The calculation of the profitability of a forest operation that neglects the forest’s regulatory functions on climate or water regime overestimates the profitability and overexploits the forest. Similarly, the use of motor vehicles in urban areas, which has so far ignored the health consequences of air pollution, has led to overuse of this mode of transport.

According to the economic theory as it was developed in 1920 by Arthur C. Pigou[11]. Such malfunctions can be avoided by internalising externalities, i.e. by making the polluter pay for the pollution he has caused (polluter pays principle). Such an operation is intended to reflect the value attributed to the environment, or the cost to society, and to constitute a “price signal” sent to economic agents. However, the theoretical prescription is simpler than its application.

But identifying and quantifying an external effect in monetary terms is all the more difficult because it is diffuse, and affects many agents unevenly, over a more or less long period of time and with often complex disturbances of the natural environment (synergy, threshold, amplification, irreversibility effects). The disappearance of a forest, for example, does not lead to identical externalities for foresters, hunters or Sunday walkers, especially if we take into account the option values, i. e. those that economic agents attach to a use in the future [12]. Given the lack of markets for services such as clean air or clean water, valuation techniques must be implemented directly (willingness to pay revealed by the overpricing of a dwelling in a low-polluted area, by a survey or “contingent valuation”) or indirectly (estimation of the value of lives lost due to certain pollutants).

Assuming that the valuation difficulties have been overcome, methods for internalising external effects in the prices of goods and services have yet to be defined. The economic analysis proposes two of them.

3. The Pigouvian tax

For Pigou, the existence of externalities separates private costs from the social cost of economic activities, which is contrary to the pursuit of collective well-being and equity (Figure 4). The gap can then be reduced by imposing on the “polluter a tax equal to the marginal social damage caused by his polluting activity” [13]. By allocating costs and profits to the polluter, the tax restores the conditions for taking social costs into account and makes it possible to achieve an optimal situation of collective well-being. Defined on the basis of a cost-benefit calculation, the level of pollution retained by the pigouvian tax nevertheless poses an intrinsic problem of measuring external costs “at the optimum”. In practice, it is often preferred a level set by a government standard based on expert diagnoses, in a cost-efficient calculation logic.

4. Markets for pollution rights or emission allowances

The second approach is due to Ronald Coase [14], also addresses the issue in another founding article “The problem of social cost“ [15]. But it does so in the name of a liberal critique of public interventionism and proposes to allow direct negotiation between polluters and victims until there is a spontaneous agreement on the acceptable level of pollution. In this case, the role of the State is to properly specify access or property rights to the environment for the polluted and the polluter. It is then up to economic agents to negotiate, until the marginal costs of reducing pollution borne by some are covered by the marginal willingness to pay of others.

However, Coase is too keen an observer of economic reality to ignore that “transaction costs” (a concept he himself invented [16]) will in many cases limit the effective possibilities of negotiation. John Dales will provide a practical solution to the difficulties of the Coasian approach by proposing in 1968 the creation of markets for environmental rights [17]. It is then on these markets of “permits” or “rights to pollute” that negotiations between the various actors can be more easily conducted.

While the Pigouvian approach faces the difficulty of assessing the cost of pollution, this second approach faces the difficulty of assessing the acceptable level of pollution. Because allowance markets can only function if the State or another public authority imposes a constraint on the rights of access to or use of the environment and on the modalities of their distribution among the various actors.

Assuming no uncertainty, the two methods of environmental regulation by price or quantity are equivalent. But things are very different in reality because uncertainty is omnipresent in environmental matters. Taking into account the relative slopes of the damage cost curve and the pollution reduction curve, Martin Weitzman provides a remarkable demonstration, because it theoretically makes it possible to decide: in the presence of uncertainty, when the slope of the reduction costs is greater than that of the damage costs it is appropriate to intervene by prices (tax) rather than by quantities (permits), and conversely when the slope of the damage costs is greater [18].

5. The reality check: progressive degradation and environmental disasters

If environmental issues have continued to gain ground in the field of societal concerns since the 1960s, it is because they reflect both a gradual increase in environmental degradation and a series of disasters. A series of events have alarmed public opinion and governments: diseases and malformations attributed to the mercury spill in Minamata Bay (Japan) until 1977; oil spills related to the stranding of the oil tankers Torrey Canyon in March 1967, Amoco Cadiz in March 1978, Exxon Valdez in March 1989; explosions at the chemical plants in Seveso (Italy) in July 1976 or Bhopal (India) in December 1984; the oil shocks of 1973 and 1979 interpreted as the beginning of a hydrocarbon shortage resulting from excessive exploitation of underground resources; the large-scale radiation risks associated with the nuclear accidents on Three Mile Island (United States) in March 1979 and especially Chernobyl (Ukraine) in April 1986, two events that preceded the Fukushima disaster (Japan) in March 2011.

Responses to these environmental impacts have differed significantly from one region of the world to another, but almost everywhere they have resulted in higher environmental standards and public policies based on the precautionary principle.

6. The exploitation of natural resources

It is impossible to put all natural resources, renewable and non-renewable, in the same basket, but some lessons can be drawn from the evolution of their exploitation and prices over the past decades. In the short and medium term, natural resource prices fluctuate strongly, but in the long term they have not increased for several reasons.

Contrary to H. Hotelling’s assumptions, the earth stock is not finished as long as discoveries of new deposits or the transformation of possible resources into proven reserves continue. This is due to scientific and technological advances that have made it possible, for example in the case of hydrocarbons, to access deep offshore resources off the Brazilian coast or Texas shale oil and gas [19].

In addition to the uncertainties of supply, there are also uncertainties of demand since, through substitution, a resource that is highly valued today may no longer be so in the future. In the energy sector, for example, demand for coal, gas or oil may well be significantly reduced as a result of an increased use of non-GHG emitting energy sources. In this context, it is difficult to imagine perfectly informed operators, therefore able to arbitrate between immediate or future extractions. Therefore, rationality does not require maximizing its gain over the entire life of the exploited resource, but rather shortening this period, which has been the case in many mining industries. As Morris A. indicated Adelman is one of the best oil specialists at MIT, the logic of producing countries is most often of the “take the money and run” type.

The result of these decisions is well known: the strong growth in extraction rates, and therefore in supply, causes prices to fall, stimulates demand, delays technological change and industrial restructuring. It accentuates the deterioration of the environment and aggravates intergenerational injustice, which could have been avoided by a regular upward price trajectory, supported by a scarcity rent. The succession of phases of high and low prices for non-renewable resources supports Krautkraemer’s analyses: these are generally traded on markets and, despite the instability of price signals, they allow supply and demand to be adjusted over the long term. Pierre-Noël Giraud says nothing else about fossil resources and the energy-climate issue. According to him, with fossil fuels we do not have a problem with resources, but a problem with garbage (CO2 being the waste from combustion and the atmosphere… the garbage) [20].

7. Rejection taxes and contracts for environmental access rights

Negative externalities, highlighted by economic analysis, are taken into account through environmental taxes, which are now widely used in all countries of the world [21]. In France, for example, several of them have proved their worth:

the fees of the Water Agencies, which date back to the 1964 Water Act, tax water abstractions and activities that present risks of pollution of water resources: their proceeds are redistributed in the form of loans or subsidies to local authorities, industrial companies and farmers for work to reduce pollution;

- the Internal Tax on the Consumption of Energy Products (TICPE) is best known for its strong impact on fuel prices; it is by far the most important since in 2015, it accounted for nearly 50% of all environmental taxes;

- since 2012 TICPE includes a carbon component, the Climate and Energy Contribution, which has been reinforced by the Energy Transition Law for Green Growth of 2015 and which should increase to 100 €/tCO2 in 2030;

- the General Tax on Polluting Activities (TGAP) applies to air pollution, pesticides, waste or products that are difficult for the environment to assimilate, such as oils, lubricating preparations or detergents.

In general, most taxes have proved effective, but their widespread use is often met with resistance from public opinion or economic actors. This reluctance is at the root of the difficult taxation of nitrates of agricultural origin or CO2 emissions. Similarly, despite its positive aspects for the rebalancing of transport, the heavy goods vehicle ecotax has not been able to establish itself in France [22]. As for the carbon tax, whose planned increase triggered the social crisis of winter 2018, its fate is still pending in mid-2019.

When taxation is considered too penalising for companies and too costly to set up by public administrations, it can be replaced by the introduction of markets for pollution rights. However, their experimentation is still limited. The United States was the first to do so with the 1990 Clean Air Act Amendment (CAAA), which established a “cap and trade system” in the form of a national market for sulphur dioxide (SO2). The rather positive results of the experiment [23] have led to similar results on carbon dioxide (CO2): the Chicago Climate Exchange brings together 350 companies in 2003; the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative brings together 10 northeastern states in 2009; the Midwestern Regional Greenhouse Gas Reduction Accord in 2010 and the Western Climate Initiative in 2012 extend this type of market to other states.

Outside the United States, after the Japan Voluntary Trading Emission Scheme involving 73 companies in 2005, the projects that were launched in Australia and New Zealand were not followed up. As a result, it is in Europe that the experience of markets with the right to pollute has gone the furthest, first at the level of the Scandinavian countries and then at the level of the European Union (EU).

After a pilot phase (January 2005-December 2007), the EU ETS entered a learning phase (January 2008-December 2012) which continues with a phase III (January 2013-December 2020). During this last phase and beyond, the main changes concern the replacement of national emission ceilings by a single European ceiling, the gradual reduction of allowances, the abandonment of their free allocation, and above all the creation of a strategic reserve. The purpose of these reforms is to raise the price of a tonne of CO2 to 17 € in 2020 and then 30 € in 2030, whereas it has been evolving since 2012 between 5 and 10 €, a level considered very insufficient to direct investment towards less emitting technologies (Figure 5). Today, it has to be said that, while the reform of the allowance market and the creation of a strategic reserve have made it possible to redress prices, the divergence of energy interests within Europe has not yet made it possible to really initiate the necessary changes in the trajectory of investment. And the question remains as to the long-term effectiveness of allowance markets, even though price signal instability is an intrinsic feature of them.

Today, it is on the Chinese side that we must look to assess the future of the CO2 quota markets. After an initial phase that tested different market structures in seven pilot markets, China is now moving towards the establishment of a national market [26]. This will initially only concern the electricity sector. Its objectives will be defined by an emission standard defined in grams of CO2 per kWh, decreasing over time. As in other areas, China is committed to learning from experience. Examination of the difficulties encountered elsewhere and internal testing of different options may suggest that the Chinese CO2 market offers more favourable prospects than its predecessors in other regions of the world [27].

8. Messages to remember

Economists must be aware of the importance of the contributions they can make to the definition of public policies, but they must also take into account the limits of their discipline:

- the “cost-benefit” analysis faces major difficulties, in particular the calculation of the value of environmental goods, which makes it largely illusory for an economist to understand all the parameters of the decision;

- the economist’s function is to identify, for a given social environmental standard, the most effective or least costly solutions;

- in the quest for efficiency, the market and price signals are not the solution to all problems, contrary to what those who advocate a single global price for CO2 to stop global warming think. They are only essential tools to change certain behaviours that destroy the environment;

- an economic analysis, reduced to the functioning of markets, is not able to take into account all the relationships by which the economy is integrated into the biosphere, via society.

We must stick to three lines of reflection and action

- leave decisions relating to public goods that cannot be appropriated outside the scope of economic theory, which is done, in particular, when the precautionary principle is applied;

- subordinate other decisions to “cost-effectiveness” rather than “cost-benefit” approaches by considering that public authorities, on the basis of sound scientific expertise, will be better able to set acceptable levels of environmental damage than a marginal cost calculation that is almost impossible to assess [28];

- develop interactions with other social sciences, to better understand the behaviour of citizen-consumers in the ecological transition and to characterize the conditions for the “socio-technical feasibility” of environmentally friendly innovations.

Notes and references

[1] Introduced by the Nobel Prize winner Paul Krutzen, the concept of Anthropocene refers to the period in history in which human activities have both identifiable and irreversible impacts on the state of the planet.

[2] Quoted by Passet René (1979). Economics and life. Paris : Economica, 292 p (p. 38).

[3] Notably by Jevons Stanley W (1965). The Coal Question. New York: Augustus M. Kelley Publisher, 467 p. In this book, published in 1865, the author develops the thesis that the continuation of coal mining in England at the same rate implies a deeper excavation of the mines and therefore an increase in costs that will inevitably affect the competitiveness of the British economy in the face of competition from Germany or the United States, beneficiaries of less expensive mines to operate.

[4] Hotelling Harold (1931). The Economics of Exhaustible Resources. Journal of Political Economy, vol. 39, pp. 137-175.

[5] The following is largely inspired by Vivien Franck-Dominique. Economy, op. cit., pp. 68-69 as well as Bretschger Lucas and Leinert Lisa (2010). The evolution of the price of natural resources. Economic Life. Revue de Politique Economique, n°11, pp. 4-9.

[6] Global commons or global public goods include cultural or natural properties that should escape any State or entrepreneurial sovereignty because they are part of a common heritage of humanity (PCH). Unfortunately, it is impossible to give a precise list because, despite international efforts, particularly within the framework of UNESCO, their definition is still not accepted by all countries.

[7] Stiglitz, Joseph E. (1974). Growth with Exhaustible Natural Resources: Efficient and Optimal Growth Paths. Review of Economic Studies, Symposium on the Economics of Exhaustible Resources. Solow, Robert M. (1993). An Almost Practical Step toward Sustainability. Resources Policy 19 (3):162-72.

[8] Krautkaemer J., Economics of Natural Resource Scarcity: The State of the Debate, Resources for the Future, 2005, https://media.rff.org/documents/RFF-DP-05-14.pdf

[9] A very comprehensive review of these controversies can be found in Pezzey John C.V. and Toman Michael (2002). The economics of sustainability. A review of journal articles. Resources for the Future, January, 25 p.

[10] Cropper Maureen L. and Oates Wallace E. Environmental Economics: a survey. Journal of Economic Literature, vol. XXX, June, pp. 675-740.

[11] Pigou A.C., The economics of Welfare, 1920, files.libertyfund.org/files/1410/Pigou_0316.pdf

[12] Henry Claude (1990). Economic efficiency and ethical imperatives: the condominium environment. Revue Economique, 41, pp. 195-214.

[13] Vivien Franc-Dominique. Economy, op. cit., p. 58-61.

[14] An English economist (1910-2013), Ronald Coase made his name, in particular, with his article “The nature of the firm” (1937), which can be read in its French translation “La nature de la firme”, Revue Française d’Economie, 1987, vol. II/1, pp. 133-163.

[15] https://www.law.uchicago.edu/files/file/coase-problem.pdf

[16] These are the costs of information, negotiation and decision, monitoring and enforcement involved in any transaction.

[17] Dales John Harkness (1968). Pollution, property and prices. University of Toronto Press.

[18] Born in 1942, Martin Weitzman teaches at Harvard University. It states: Weitzman Martin L. (1974). Prices vs quantities. Review of Economic Studies, 4(4), pp. 477-491. Weitzman Martin L. (1978). Optimal rewards for economic regulation. American Economic Review, 68 (4), pp. 683-692. Criqui Patrick (2009). At the heart of the future international climate regime: taxes or CO2 quotas? In Tirole J. (ed.). Climate policy: a new international architecture. Paris : La Documentation française. pp. 261-270.

[19] Phenomena not taken into account by the proponents of the peak oil thesis that we had criticized from the outset. Martin Jean-Marie (1999). Concerning “The end of cheap oil”. Energy Policy, vol. 27, 2, February, pp. 69-72.

[20] In L’homme inutile: du bon usage de l’économie. Odile Jacob, 2015.

[21] Rotillon Gilles (2007). Environmental taxation, a tool for environmental protection. Regards croisés sur l’économie, n°1, pp. 108-113.

[22] Its launch was stopped in October 2013 by the violent opposition of the Breton “Red Caps” to a heavy goods vehicle tax similar to an ecotax.

[23] A very detailed analysis of this market is provided by: Schmalensee Richard and Stavins Robert N. (2012). The SO2 Allowance Trading System: The Ironic History of a Grand Policy Experiment. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, August 3, pp. 1-23…

[24] In the very abundant literature on the subject, a study of the foundations of the EU ETS can be consulted with benefit: Ellerman A. Denny, Joskow Paul L. (2008). The European Union’s Emission Trading System in perspective. Pew Center on Global Climate Change, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 50 p.

[25] The allowances are allocated annually by each EU Member State on the basis of past emissions adjusted by a reduction factor.

[26] Guoyi Han and others. China’s carbon emission trading. Stockholm: Forests, 56 p, and more recently, China: the carbon market, Enerpresse n°11 976, 22 December 2017.

[27] Launched at the end of 2017, this market, which is currently limited to the electricity sector, will not really become operational until 2020.

[28] For more details, see Patrick Criqui, Benoit Lefèvre (2010), in B. Zuindeau, ed. : Sustainable Development and Territories, p. 193.

The Encyclopedia of the Environment by the Association des Encyclopédies de l'Environnement et de l'Énergie (www.a3e.fr), contractually linked to the University of Grenoble Alpes and Grenoble INP, and sponsored by the French Academy of Sciences.

To cite this article: MARTIN-AMOUROUX Jean-Marie, CRIQUI Patrick (January 6, 2020), Economic theories in the face of the realities of environmental crises, Encyclopedia of the Environment, Accessed July 27, 2024 [online ISSN 2555-0950] url : https://www.encyclopedie-environnement.org/en/society/economic-theories-in-the-face-of-the-realities-of-environmental-crises/.

The articles in the Encyclopedia of the Environment are made available under the terms of the Creative Commons BY-NC-SA license, which authorizes reproduction subject to: citing the source, not making commercial use of them, sharing identical initial conditions, reproducing at each reuse or distribution the mention of this Creative Commons BY-NC-SA license.