Natural disasters: when the environment becomes a threat

PDF

The environment becomes threatening when nature expresses its devastating power through natural disasters that directly affect societies. This article aims to show how natural disasters have evolved in recent years and what their impacts have been on people. We explain how science approaches the environment when it becomes a threat and what tools are used to observe, understand, model and predict natural phenomena and their possible impacts. Finally, we explain how this research can be useful to operational actors in managing disaster situations and what developments are needed in how we view our relationship with nature, to cope with environmental changes and future natural disasters.

1. When the environment becomes a threat

“Floods in Ile de France”, “Major flood in Paris” headline in the newspapers in June 2016. Nature once again recalls its power and worries inhabitants and public authorities when the environment becomes a source of risk for populations, their property and their activities. This raises the question of how researchers can help to understand these phenomena. How can this knowledge contribute concretely to reducing the number of victims and impacts?

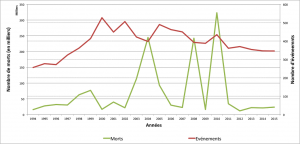

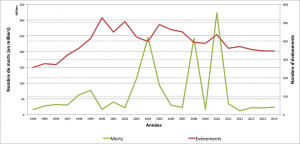

While these figures show that a single earthquake can be particularly deadly, climatic phenomena such as floods, storms, heat waves and heat waves are also to be feared in a context of climate change. In France, for example, of the 86 events that have struck the country over the past 20 years, the most deadly are extreme temperatures, with more than 24,000 deaths. We remember in particular the heat wave of 2003 causing 15,000 deaths, mainly among the elderly (link to article Climate change: effects on human health).

2. Understand the processes involved

The first scientists to focus on the risk-generating environment were earth or climate scientists. Their work has led to a better understanding of the physical processes involved in natural disasters. The research that continues to be developed in this area is essential, but it alone does not allow us to understand why some regions of the world are more affected by natural disasters than others. Let us look back at 2003. Algeria was hit on 21 May by the 6.7 magnitude Boumerdès earthquake, which killed 2,300 people, injured 10,200 and left 180,000 homeless [2]. A few days later, on May 30, Honshu province in Japan also suffered a 7.0 magnitude earthquake, causing no deaths, only minor damage to buildings and about 100 injuries [3]. On December 26, however, the 6.5 magnitude Bams earthquake struck south-east Iran, killing 35,000 people, injuring 30,000 and destroying almost the entire city [4]. How can such differences between the impacts of comparable earthquakes be explained in terms of magnitude? To understand it, it is necessary to take into account other explanatory factors, particularly human ones.

As early as 1755, following the earthquake that destroyed the great European capital Lisbon, killing some 60,000 people, exchanges between Rousseau and Voltaire raised the question of social responsibility in natural disasters. Voltaire defends a naturalistic vision of the event and sees it as an unfortunate coincidence. Rousseau opposes this with a completely different vision, noting that Lisbon is built on an area known for its seismicity, and that its development involved endangering the very large population that was concentrated there. He has no doubt about the social responsibility of the disaster (Bouhdida, 2014, [5]). This debate heralds a major shift in the way we think about the links between risk and society. With the parallel development of the industrial society, we then enter what the German sociologist Ulrich Beck will call “the risk society” [6]. Contemporary risks no longer come only from the outside as natural disasters are generally thought of, but they are also produced by society through its industrial activities and the use of technological advances [7].

In this context, how to understand the complexity of the environment defines as a risk, how to define its social dimension? The preferred approach was to study vulnerability. This notion is defined by Wisner et al as the probability of suffering injury or even death, deterioration or loss of livelihood assets [8]. This probability depends on multiple factors, which researchers are working to define and evaluate. Reducing risks must therefore also include limiting the vulnerability of companies and their assets and activities.

But reducing vulnerability requires an understanding of its mechanisms. Yet “disasters are real indicators of human and territorial vulnerabilities within affected communities and societies” [9]. It is therefore from natural disasters themselves that researchers are trying to better understand what vulnerability is, how it is expressed, in an attempt to reduce it. The work in this field has thus made it possible to identify certain specific factors. Poverty is a major factor in addressing global vulnerability: the poorest populations are also the ones most affected by natural phenomena. But recent events, such as Hurricane Katrina in the United States in 2005 or the Fukushima earthquake in Japan in 2011, highlight that poverty is not the only factor at stake. Other causes can increase or reduce the vulnerability of societies and territories. Examples include organizational or political factors: is society prepared for such events, can institutions react in time to limit impacts?

A natural disaster is therefore the result of the combination over the same space and time of a physical phenomenon (climatic, hydrological, geophysical) and a society characterized by a greater or lesser vulnerability to this phenomenon. Understanding what happens when the environment becomes a risk therefore requires an understanding of the multiple dimensions of the complex physical and social phenomena that take place on the site and over the time of the event.

3. Observe and model to predict

This interdisciplinary work is carried out in stages, throughout the treatment chain, which makes it possible to understand natural risks. Observation and data collection is an essential phase in understanding both physical and social processes. However, modelling can sometimes be useful in association with field observations. It consists in producing a reduced model of the situation to test the role of certain constraints or factors that are difficult to observe. For example, we reproduce the floodable road network and look at the variables that affect people’s exposure on these roads: the time of departure, the decision whether or not to cross certain critical points, or the route taken, for example [11]. Modelling thus makes it possible both to better understand what happens during the event and to exaggerate certain constraints to test particular hypotheses: if all individuals leave at the same time, take floodable routes and continue their journey regardless of the situation, what is the proportion of individuals who put themselves at risk? The idea is therefore not to accurately reproduce reality, but rather to give oneself the means to test the role played by the various factors involved in the process.

Models have long been used by natural scientists to better understand complex natural phenomena, such as the circulation of cloud masses in the atmosphere. It is on the basis of existing models at different scales and by coupling them with field observation, that Météo France’s forecasters are able to indicate the weather in the coming days and even weeks [12]. They can predict in advance certain extreme events (with varying degrees of certainty) such as storms, heavy rains, storms, heat waves (see the Air section for more information on weather events). Being able to predict these impacts is one of the objectives of current research. However, much remains to be done to improve the overall understanding of what happens when the environment becomes threatening and to be able to deliver this type of information.

This is all the more true since some events, such as the Fukushima tragedy in Japan in 2011, highlight very high levels of complexity. How can we predict that an earthquake and the subsequent tsunami will cause sufficient damage to a nuclear power plant that, combined with various hesitations and human errors, they will lead to the devastation of an entire region? When the combined forces of nature and man mingle to become an even greater threat, how can societies anticipate, prepare and protect themselves? These questions are at the heart of current research on risks, particularly in the face of climate change. Observation, analysis and modelling efforts are still required to meet the environmental challenges ahead.

4. Addressing current environmental challenges

To see the environment as a potential danger therefore implies reconsidering man’s relationship with nature and its devastating power. Over the past centuries, science has made it possible to advance in the understanding of natural phenomena and to implement technical solutions that ensure a certain control of the phenomena. The combined work of historians and hydrologists clearly shows all the technological advances made since the 19th century to limit the impacts of natural phenomena, particularly floods [13]. Despite this, dramatic events of natural origin regularly raise the question of the real control of nature by mankind, encouraging great humility.

The awareness of the great changes taking place on a global scale, of the social responsibility of these great changes, thus invites us to reconsider our relationship with nature. Some social science researchers are questioning these new reports and the solutions that emerge from them, particularly in the face of the challenges of climate change. In addition to the concept of risk and vulnerability, there are also the concepts of adaptation and resilience. The latter concept is defined very differently. Based on the proposed definition in psychology, resilience applied to the territory means knowing how to “find the necessary capacities to adapt to hazards” [14]. The idea is therefore not to seek to control nature to prevent phenomena from occurring, but rather to find the internal resources of societies and territories to cope with events and limit their impacts. This new approach to risk highlights the responsibility of everyone, from the individual to society as a whole, in identifying and mobilizing these resources. To be useful in this respect, research must also be able to provide knowledge that allows us to understand environmental processes in all their complexity and help human societies become more resilient.

References and notes

[1] Catholic University of Leuven, Belgium, See http://www.cred.be/ and http://www.emdat.be/database

[2] BRGM, “Boumerdès earthquake (Algeria) of 21 May 2003. The dramatic consequences of the thousand leaf effect”[Online], accessed July 19, 2016, available at URL www.brgm.fr/sites/default/files/evenement_exposition_seisme_img08_original.pdf

[3] IRSN, “Myiagi Earthquake (Japan) of Monday 26 May 2003, Magnitude 7 at 9:24 GTM”,[Online], put online on 30 May 2003, accessed on 19 July 2016, available at URL www.irsn.fr/FR/connaissances/Installations_nucleaires/La_surete_Nucleaire/risque_sismique_installations_nucleaires/Documents/irsn_Seisme-Japon_052003.pdf

[4] CNRS, “Bam 2003: a devastating earthquake”, CNRS Théma,[Online], online before December 2005, accessed 19 July 2016, URL: www2.cnrs.fr/presse/thema/724.htm

[5] BOUHDIBA, S. “Lisbon, November 1, 1755: a coincidence? Au coeur de la polemémique entre Voltaire et Rousseau”, Carnet de recherche hypothèses “Presque Partout”[On line], put online on 19 October 2014, consulted on 27 April 2016, available on URL: http://presquepartout.hypotheses.org/1023

[6] BECK, U. (2001) – The Risk Society. On the way to another modernity, translated from German by L. Bernardi. Paris, Aubier, 521 p.

[7] BOUZON A., “Ulrich Beck, La société du risque. On the road to another modernity, translated from German by L. Bernardi”, Communication Questions[Online], 2 | 2002, online on 23 July 2013, accessed 19 July 2016, available at URL: communication questions.revues.org/7281

[8] WISNER, B., BLAIKIE P., CANNON T., DAVIS I. (2004). At Risk.Natural hazards, people’s vulnerability and disasters.Second edition (1st edition in 1994). New York, Routledge, 470 p.

[9] LEONE, F., VINET, F. (2006). Vulnerability, a fundamental concept at the heart of natural risk assessment methods – In : LEONE F. and VINET F. (dir.) : “The vulnerability of societies and territories to natural threats”. Geographical analyses. Géorisques, n°1, coll. de l’Equipe d’Accueil GESTER, Ed. publications de l’Université Paul-Valéry-Montpellier 3, pp. 9-25.

[10] RUIN, I., CREUTIN, J. -D., ANQUETIN, S., LUTOFF C. (2008). Human exposure to flash floods. Relation between flood parameters and human vulnerability during a storm of September 2002 in Southern France. Journal of Hydrology, 361(1-2): 199-213. DOI:10.1016/d.jhydrol.2008.07.044

[11] SHABOU, S., RUIN, I., LUTOFF, C., DEBIONNE, S., ANQUETIN, S., CREUTIN, J.-D. (2016). MobRISK: A large-scale activity-based mobility model for assessing exposure of road users to flash flood events. Journal of Transport Geography, Submitted

[12] METEO FRANCE. Weather Forecast,[Online], accessed April 27, 2016, available at URL: http://www.meteofrance.fr/nous-connaitre/activites-et-metiers/la-prevision-meteorologique.

[13] LANG, M., HEART, D., BROCHOT, S. (2003). Historical information and engineering of natural hazards: the Isère and the Manival torrent. Vol. 18, Editions Quae.

[14] Villar Clara and David Michel (2014) Resilience, a tool for territories? Paper published at the IT-GO Rosko 2014 seminar (Roscoff, 22-23 May 2014). Website of the IT-GO Rosko 2014 seminar: http://roscoff14.catalyse.info/

The Encyclopedia of the Environment by the Association des Encyclopédies de l'Environnement et de l'Énergie (www.a3e.fr), contractually linked to the University of Grenoble Alpes and Grenoble INP, and sponsored by the French Academy of Sciences.

To cite this article: LUTOFF Céline (February 11, 2019), Natural disasters: when the environment becomes a threat, Encyclopedia of the Environment, Accessed July 27, 2024 [online ISSN 2555-0950] url : https://www.encyclopedie-environnement.org/en/society/natural-disasters-when-environment-becomes-a-threat/.

The articles in the Encyclopedia of the Environment are made available under the terms of the Creative Commons BY-NC-SA license, which authorizes reproduction subject to: citing the source, not making commercial use of them, sharing identical initial conditions, reproducing at each reuse or distribution the mention of this Creative Commons BY-NC-SA license.